Historian Aaron Marcus has thought about telling the story of Colorado's queer communities since he was in graduate school. He's written scholarly articles and worked on documentaries about the subject. In 2015, he almost had the chance to curate an exhibit at History Colorado, where he'd worked as an intern since 2008, but a tough financial year and ensuing layoffs at the institution forced him to scrap the project. Now, Marcus has another shot.

History Colorado announced Wednesday that they hired Marcus as their first-ever associate curator of LGBTQ history, a two-year position funded in partnership with the Gill Foundation that will culminate in an exhibit showcasing his findings. He actually started work last October, but his hire was under wraps until this week. The new position is one of several as History Colorado works to broaden representation within the state's official historic archive. They are set to hire associate curators of oral history and Hispanic, Latino and Chicano history in the coming months. A curator of architecture has already joined the team.

Marcus said positions like his help address a historic problem for historic archives. For a long time, white, straight men held the sole power to write the stories of America's past. It meant interpretations of collections like History Colorado's tended to focus on people who looked like those in power.

"History is known for keeping the history of white men," he said. "Everybody should be represented."

Marcus said he identifies as gay, but he doesn't think it's a necessary qualification for his job. Instead, it was his passion for the subject that he said made him the right candidate.

Dawn DiPrince, History Colorado's chief operating officer, said giving curators specific agency to flesh out alternate perspectives means present and future generations have a chance to appreciate historic diversity that otherwise may be forgotten.

"We believe that our collection needs to reflect the rich diversity of the state of Colorado." she told Denverite. "The specialty curator positions help us achieve that in ways that we, as a 140-year-old institution, have not yet fully realized."

Marcus said he's excited to discover hidden treasures in the state archive and search Colorado for more unheard stories.

"For me personally, to be able to continue this, is incredible," he said, surrounded by boxes in History Colorado's library. "It's great that people are actually going to get to see it now, and I've found stuff that has surprised a lot of people - even me - that goes back to the 1950s."

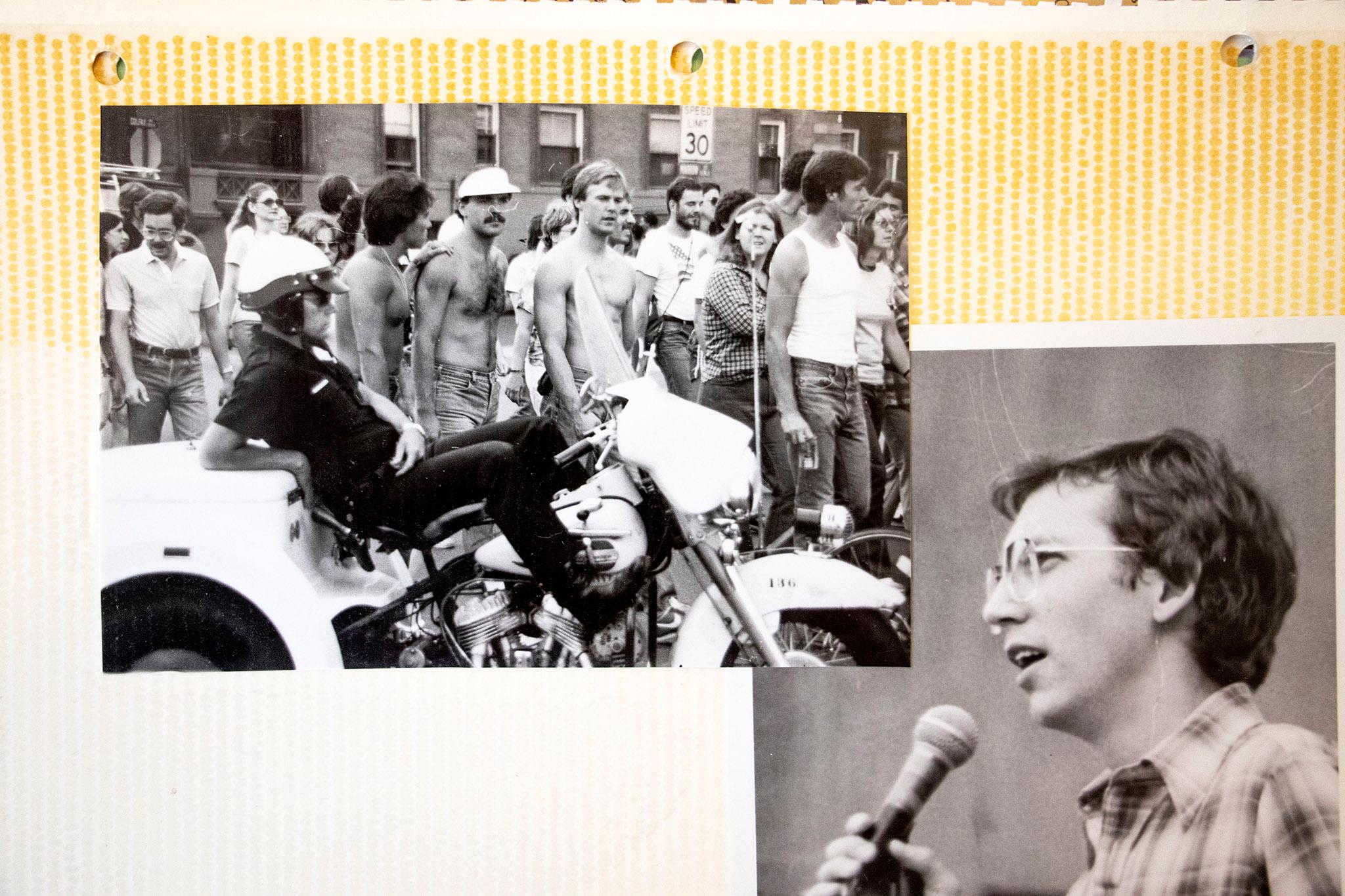

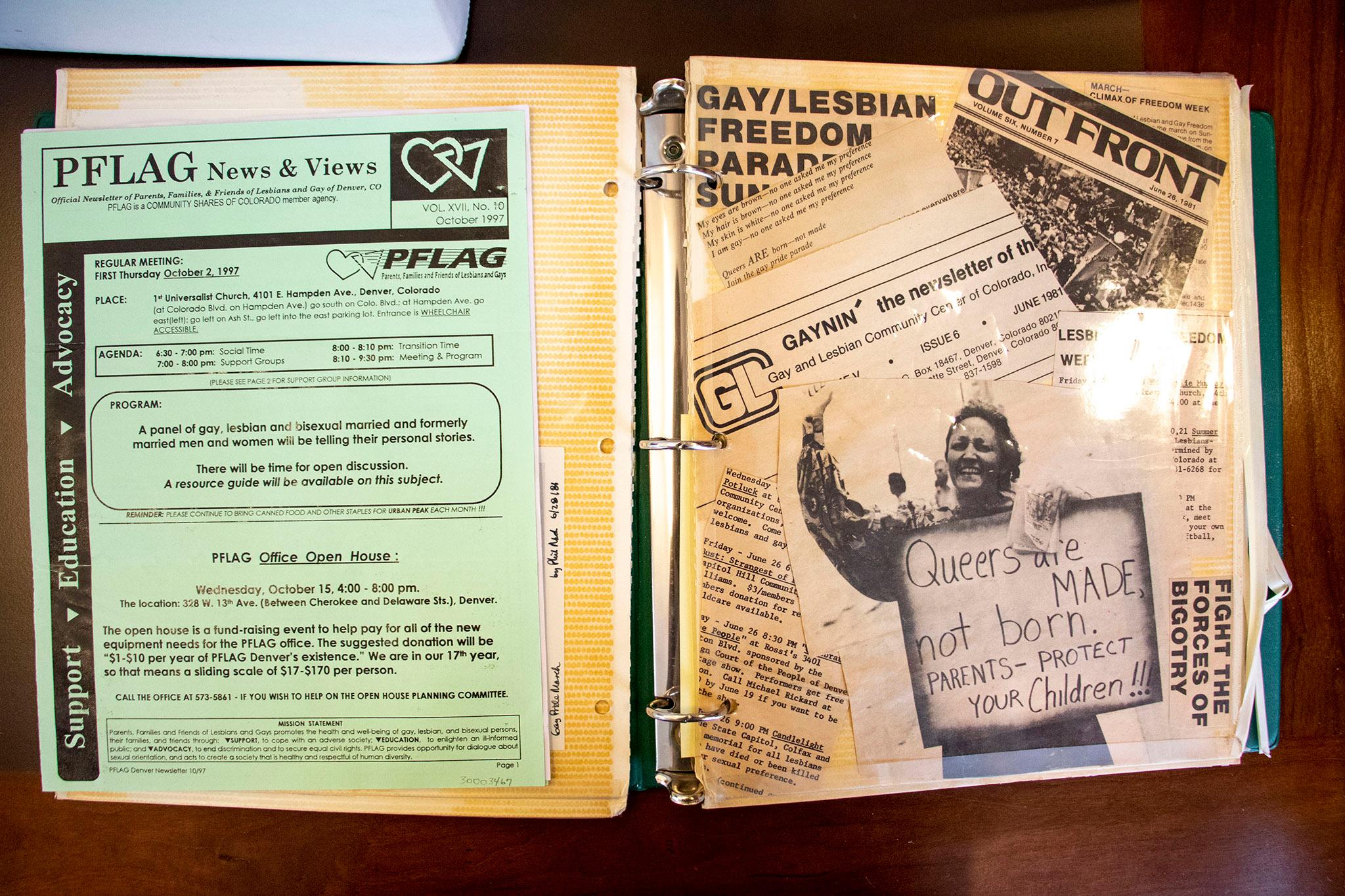

The history he traces goes all the way back to the 1800s, when newspapers published articles suspicious of queer-friendly businesses. Marcus has documents from the Colorado chapter of the Mattachine Society, a secret group founded in 1950 that aimed to reframe gay rights in line with racial civil rights movements of the time. More items in the growing collection come from gay and lesbian bars and associations from the '70s and '80s, an era when police regularly raided establishments and restaurant owners used phone trees to warn each other of coming danger.

Many of the items come from people who sought to collect queer history before it was acceptable for a state institution to shoulder the responsibility. He has huge boxes of documents, flyers, posters and photographs, for instance, from the Gay Community Center of Colorado, which became the Center on Colfax.

One folder in the museum's possession came from Mickey McShan, a Texan who moved to Denver before his apparent death sometime around 1990. McShan had AIDS, and his letters show an urgency to find a good steward for his collection of bar matchbooks, bathhouse membership cards, postcards and more.

"If it wasn't for us, he'd be lost forever. And now we have a piece of Mickey and anybody can come, you know, meet him," Marcus said. "There's actual pictures of him and it puts a face on it."

Marcus also discovered he wasn't the only state archive employee to try to bring this history to light.

In his search, he discovered a dossier of objects and records collected by Stan Oliner. It was a huge help to Marcus' work, but the story of who Oliner was and why his research never reached the public eye is still a mystery. Oliner died in 2012. Tom Parson, a local printmaking guru, said he knew Oliner as a scholar of a wide range of topics (including printmaking), but was unaware of his pursuits in cataloguing LGBTQ+ history. Denverite is still looking for people who knew him.

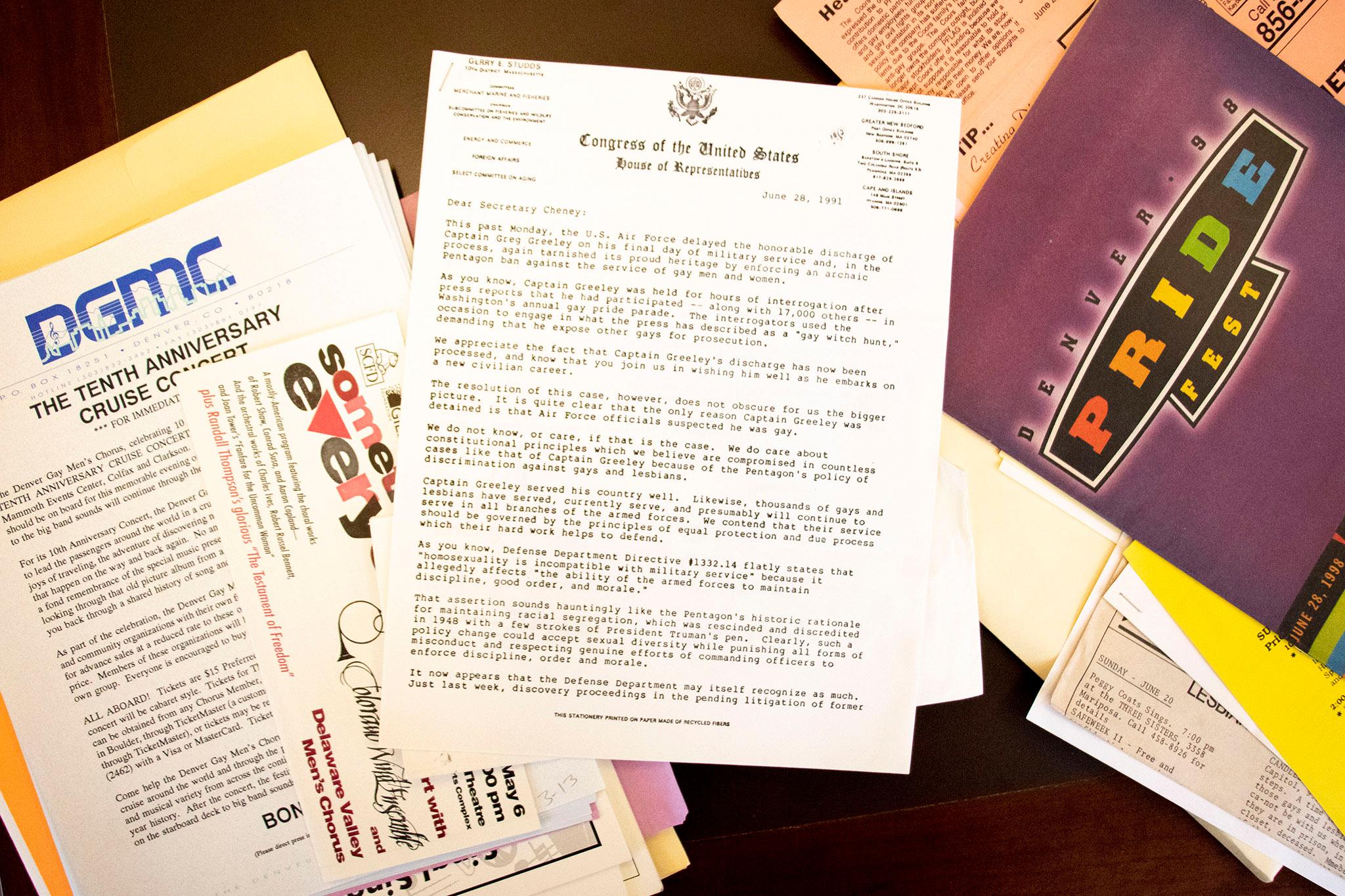

Marcus also collected program guides from Denver PrideFest, which begin as slips of paper in the 1980s and grow into voluminous books through the years. His boxes contain letters and meeting minutes and materials used to fundraise as the AIDS crisis rocked communities in the state and around the nation.

"What is really cool about that is a lot of stuff was going on nationally," he said. "What I found in here was the local component."

And then, in 1992, Colorado had a moment on the national stage. The state legislature enacted Amendment 2, a measure that outlawed anti-discrimination measures meant to protect LGBT people from losing jobs, housing and medical care. Marcus said it was a moment of reckoning, a benchmark that will be important to his interpretation of his findings.

"Going from 1992 when we're known as the 'hate state' to having an openly gay governor is huge," he said.

On one hand, Amendment 2 represented a dark time for gay and lesbian movements. But Marcus said it also sparked a new era of activism. Suddenly "relatively quiet people" were compelled to do something.

"Something so basic happens, they get fired from their job just because they're gay," he said. "Legislation like this is passed to discriminate against everybody and they become radicalized, if you will, and a leader in the movement."

One of those people called to action was Tim Gill, namesake of the organization supporting Marcus' new role.

Brad Clark, the Gill Foundation's president and CEO, said Amendment 2 galvanized people like Gill.

"So many leaders in our community rose to the occasion," he said. "If not for the work these people put in ... LGBT people would not enjoy the protections we have in Colorado."

Marcus said it's important that Colorado presents this history of struggle with open eyes and celebrates the progress LGBTQ+ people have made in recent decades. His exhibit will be aimed at the audiences of today, but the collection is meant to last in perpetuity for whatever our society looks like in a century.

"The whole point of this is so that, in 50 years, somebody can do the type of research I've done," he said. "Who knows what it'll look like? I mean, we think it's going to be very progressive and everything will get better, but we have no idea. In 50 years, they might look back and be like: wow, these people were crazy and liberal."

While he's digging through History Colorado's massive archive, Marcus says he also plans to engage people across the state in hopes of finding more objects and stories that have otherwise gone unnoticed.

"I'm hoping people dig through their attics and basements and find all this amazing stuff," he said.

But he added oral histories may be the most crucial component to his work. So many of the people who fought for equal rights from the 1950s to the 1980s are getting older. He wants to make sure someone else like Mickey McShan or Stan Oliner does not go uninterviewed.

"That's why that's so important to try to get all these stories while we can."