Workplace shootings in the popular imagination involve disgruntled employees acting out real or perceived grievances on their bosses and co-workers. "Going postal," though that's a term you hear less and less, as violence seeps into every nook and cranny of American life.

What happened Tuesday in Lower Downtown had that look and feel in superficial ways. The 911 calls about a man with a gun. The flooding of the streets with law enforcement in tactical gear. The social media videos of people streaming out of the evacuated blocks with their hands above their heads. The initial reports of multiple victims being taken away by ambulance.

It turned out that there was a single victim, 52-year-old Cara Russell, executive director of the Colorado Association for Recycling. Her husband, Mickey Russell, shot her multiple times and then killed himself. Cara Russell had recently filed for divorce.

The shooting was an act of domestic violence. And that's actually exactly what a workplace shooting looks like.

Homicide is a leading cause of workplace death for women. Depending on the year or years being looked at, it's either the first or second most common way that women die at work.

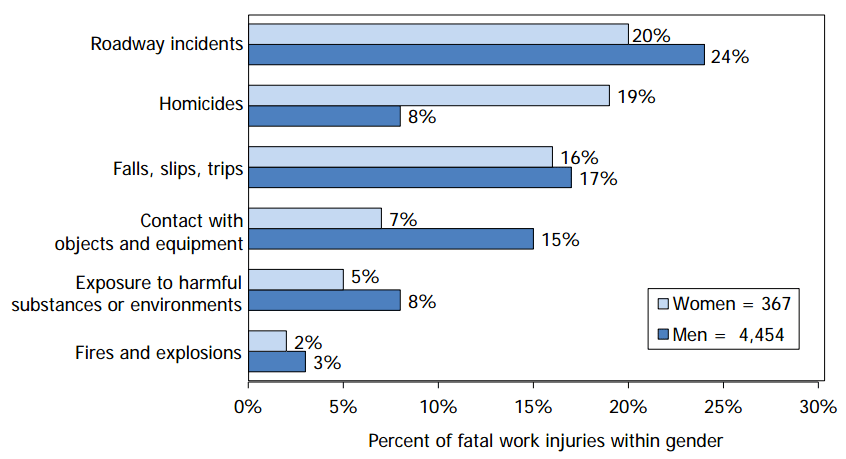

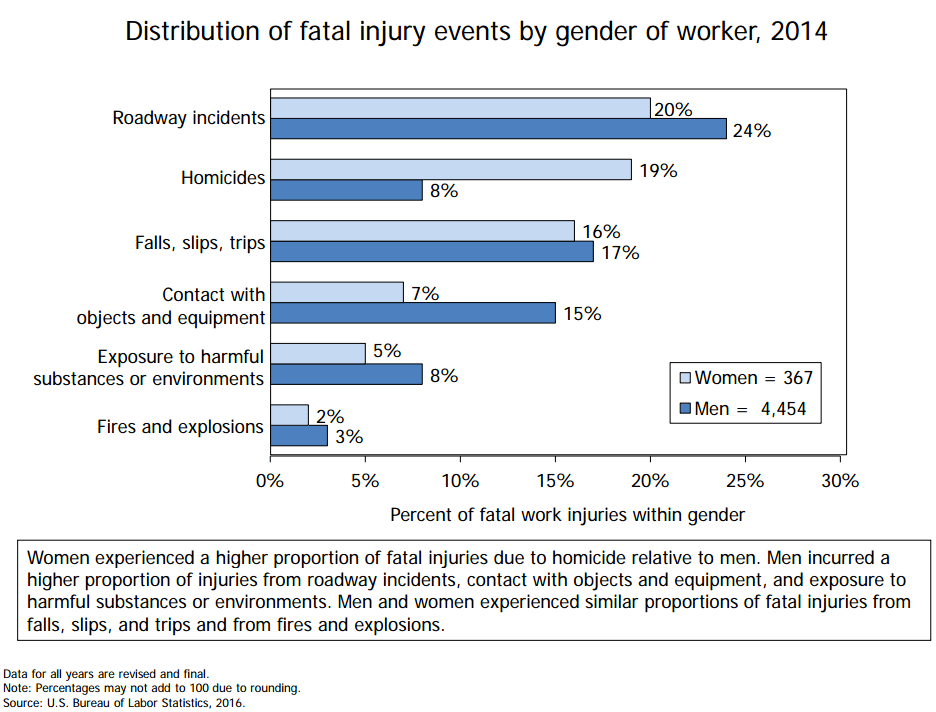

The Bureau of Labor Statistics keeps a grim list, the Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries. In 2014, homicides accounted for 8 percent of all workplace deaths and 8 percent of workplace deaths for men. They accounted for 19 percent of workplace deaths for women, a very close second behind transportation accidents at 20 percent. When men are murdered at work, it's most commonly in the course of a robbery, but for women, it's more likely to be someone they know.

About a third of women murdered at work are killed by intimate partners. That's husbands, boyfriends and exes.

Intuitively, we already know that this is the case.

No one is surprised when the police say that the victim and the shooter know each other. No one is surprised when he turns out to be an ex-husband or a boyfriend. We might even take a twisted comfort in it. This killing was targeted, not random. I can be sad, but I don't need to be scared for myself.

"It is fortunate that he didn't go in there on a bend to kill everybody and anybody," Denver Police Cmdr. Ron Saunier said at a press conference Wednesday morning, even as he called the killing a "tragic situation."

Saunier didn't word that in the most sensitive way possible, but we all know what he means. And he's right that domestic violence doesn't always limit itself to the primary target. A large portion of mass shootings are acts of domestic violence at their core.

Everytown for Gun Safety, an advocacy group, analyzed 133 mass shootings over a seven year period. The group found 56 mass shootings that involved a partner or former partner and another 20 that involved another family member.

There was a noteworthy connection between mass shooting incidents and domestic or family violence. In at least 76 of the cases (57%), the shooter killed a current or former spouse or intimate partner or other family member, and in at least 21 incidents the shooter had a prior domestic violence charge.

The connection between prior domestic violence and mass shootings is starting to draw more attention. Omar Mateen's ex-wife described a man who beat her severely and tried to control her every move before she escaped their marriage. In the New York Times, Amanda Taub speculates about the stew of grievance and entitlement that might connect domestic violence and mass shootings.

But far more common is the man who kills just his wife or ex-wife, girlfriend or ex-girlfriend.

In an analysis of 2013 homicide data, the Violence Policy Center found 895 women killed by an intimate partner, 62 percent of all female murder victims that year. Those numbers include only a single victim killed by a single attacker. Of those, 280 were killed in the course of an argument or fight. The rest were killed in more calculated acts.

In Colorado, of 151 homicides in 2014, 25 were women killed by an intimate partner. More than 70 percent of murder-suicides are acts of domestic violence, and 94 percent of victims are women, according to information compiled by the National Coalition Against Domestic Violence.

Abusers shoot women at work because it's easy to find them there.

The most dangerous time for victims of domestic abuse is when they try to leave. A woman who leaves her partner can find a new living arrangement and change her phone number, but she'll probably keep going to the same job.

"It's access," said Lydia Waligorski, public policy director at the Colorado Coalition against Domestic Violence. "Your guard is down at work. The doors are open. There are other people around. It's a place where you feel safe.

"Survivors cannot be survivors 24 hours a day without losing their minds," she added. "Especially as women, we're taught there is safety in numbers."