The tenth-grade North High School biology teacher enthusiastically draws circles and arrows on a cell diagram.

While some students dutifully copy it into their notebooks, others giggle and whisper. A boy and a girl seated next to each other playfully pull each other’s hair. The teacher walks over and stands right in front of them. They stop, but the giggling continues elsewhere.

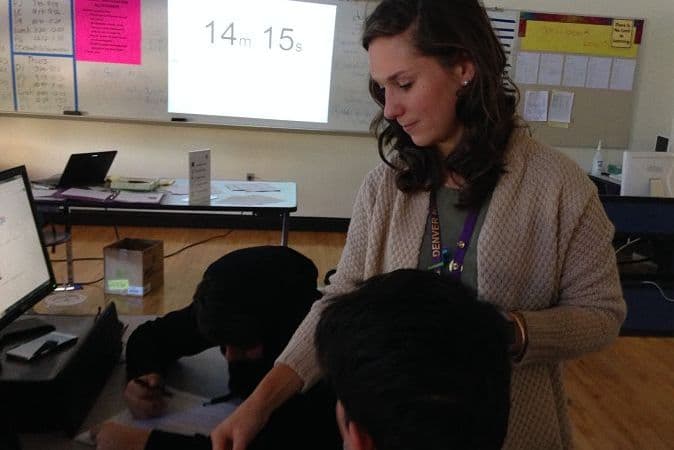

Fellow science teacher Carly Buch watches the lesson unfold and then slips out the heavy wood door at the back of the classroom. She heads to an office to debrief what she’s seen with Elizabeth Gorka, North’s dean of instruction.

Together, they craft an email suggesting the teacher remind her students of behavior expectations so they don’t become distracted by side conversations — providing immediate feedback before Buch is scheduled to meet with the teacher in a few days.

This is what Denver Public Schools’ “teacher leadership and collaboration” program looks like.

Buch is a “senior team lead” — or, in layman’s terms, a teacher/coach — who teaches part of the day and spends the rest of her time observing other teachers, giving feedback and helping them plan lessons and think through problems that arise in their classrooms.

DPS has put a lot of stock in the program, which started in 2013-14 as a grant-funded pilot with 40 schools. It’s now in 113 schools, and the district would like to expand it next year to nearly all of them.

But that will take more money — which is why a $56.6 million tax increase, or mill levy override, Denver voters will consider next month includes $9.8 million for the program. The main cost comes from hiring additional teachers to teach while the teacher/coaches are coaching.

“If we know the teacher is the x factor,” said Kate Brenan, the district’s director of teacher leadership and career pathways, “then teacher leadership allows us to provide more consistent opportunities for support, feedback and improvement.”

DPS bond and mill levy

Denver voters will be asked in November to pass a $572 million bond issue and a $56.6 million mill levy override, known as 3A and 3B, to support Denver Public Schools.

Here’s a quick rundown of how the money would be used:

- $252 million in bond money for school maintenance.

- $142 million in bond money to build new schools and expand others.

- $108 million in bond money for classroom updates.

- $70 million in bond money for technology such as computers.

- $15 million in mill levy money to hire more school psychologists, social workers and nurses.

- $14.5 million in mill levy money for teacher programs, including expanding one in which teachers coach their peers and investing in increasing the diversity of the workforce.

- $8 million in mill levy money for programs that help students get ready for college or careers.

- $6.8 million in mill levy money for early literacy efforts.

While it’s not a silver bullet that will cause test scores to immediately skyrocket, she said, the district sees it as a way to help teachers grow — which leaders hope will in turn increase the number of third-graders who can read or ninth-graders who’ve mastered algebra.

The district doesn’t know yet if that’s happening. According to Brenan, it has yet to crunch the numbers to determine the program’s impact on student learning — something she said district staff is planning to do using the test scores released last month by the state.

And DPS isn’t alone. A comprehensive literature review published in June in the Review of Educational Research found no recent research on the topic.

What district officials do know is that teachers like it. In a May survey, 87 percent of participating teachers said they were glad their school was taking part in the program. Eighty-six percent said working with a teacher/coach had improved their teaching practice and 85 percent reported the feedback from their teacher/coach was “useful and actionable.”

Anecdotally, teachers say the coaching is making a difference for students, too: Eighty-two percent of participating teachers agreed it had “positively impacted their students’ performance.”

“We know there’s a large achievement gap,” Gorka said, referring to the difference in test scores between white students and students of color, and poor students and their wealthier peers.

“We know what is going to move kids fastest is having effective instruction happening in the classroom every day. When the principal and the assistant principal are the only ones able to give feedback, that doesn’t happen as consistently as it needs to. With (the teacher/coach model), we’re able to be in all teachers’ classrooms much more regularly.”

Buch has experienced the program from both sides. Last year, as a full-time science teacher, she was paired with Jennifer Engbretson, an experienced math teacher who had taken on the role of coach. Buch wasn’t new to teaching — in fact, it was her fourth year in the classroom — but she said she grew more that year than she ever had in the past.

“My coach was in my classroom once a week last year,” she said. “She knew me, she knew my kids.”

It made a difference that Engbretson was a teacher, too, Buch said.

“It was nice for me last year when Jen would be like, ‘You’re focusing on that. Want to see how I did it today?’” she said.

For her part, Engbretson said coaching other teachers has helped her improve, as well.

“Anytime you get to watch someone else’s practice, you grow in your own,” she said. “The fact I get to watch nine different people with nine different styles pushes my thinking also.”

North High social studies teacher Ryan McKillop, in her first year as a coach, agreed.

“I’m able to co-plan with them because I know the (academic) standards and the direction our department is going,” McKillop said. She said she thinks of herself as a “thought partner” for her teachers, not a supervisor there to judge how they’re doing.

Some DPS teacher/coaches also help evaluate teachers through scored observations, which can affect a teacher’s pay and whether they get tenure. In the May survey, 84 percent of participating teachers said they feel confident in their coach’s ability to do that.

Buch said she appreciated being evaluated by Engbretson last year rather than by an administrator. If Buch was having an off day — because the copier jammed and her handouts weren’t ready or because she was trying a new teaching technique — Engbretson had the flexibility to switch from being an evaluator to being a co-teacher.

“I am a coach first and I am an evaluator second,” Engbretson explained. She said she tells her teachers that “if there is ever a time you want to take a risk, I’m not going to evaluate you because you’re trying to do better. I’ll come back and evaluate you a different day.”

Liz Barkowski and Catherine Jacques of the Washington, D.C.-based American Institutes for Research said the evaluation piece is part of what makes Denver’s program stand out. While school districts across the country are experimenting with teacher leadership programs, they said, few are as sophisticated or give teachers as much responsibility.

“The fact that in Denver, these teacher-leaders are grounded in teaching in the classroom and contribute to those evaluations and provide high-quality feedback, that’s really unique,” said Barkowski, a senior researcher who has studied several teacher leadership initiatives.

District officials hope that opportunity will convince good teachers who want to advance in their careers — and salaries — to stay in the classroom rather than leave to become administrators. DPS “team leads,” who don’t contribute to teacher evaluations, get a $3,000 stipend while “senior team leads,” who do, get $5,000, according to Brenan.

The senior team leads at North said the ability to do both — and to do both at the school where they already teach — is what attracted them to apply for the positions.

“I’m not ready to leave the kids,” said Engbretson, who said teaching her own classes is still the most fun part of her day. “But I also don’t just impact 40 students a day. I impact 900.”

Chalkbeat is a nonprofit news site covering educational change in public schools.