Think of Colorado's elections offices as Amazon in reverse. Some 3 million Coloradans may mail their ballots to central locations this fall. Those envelopes have to be opened and their contents unpacked before it's all turned into digital information.

It's an unusual logistical challenge, and Denver Elections has had to invent its way to a solution that includes, no joke, a laser-powered envelope slicing machine that your local government helped develop.

"I was cautiously optimistic. I was like, ‘A laser? We don’t have that technology,'" said Drake Rambke, ballot operations administrator. "We were the first ones in the country to have that."

Just next to him, an elections judge fed envelopes into a boxy metal machine. A laser inside the sarcophagus cuts a window in each envelope, exposing where the voter's signature should be. A camera feeds the image of the signature to a bipartisan pair of judges who compare it to the signature on file for that voter.

The machine, Rambke says, was developed to Denver's requirements by Bell & Howell. Denver and Colorado are basically a laboratory for mail-in voting. It was a popular method here even before the state instituted it for all elections in 2013, and it's a big part of why Colorado had the third-highest voter turnout in 2012.

No, it doesn't matter if you ignored your privacy sleeve.

I sent my ballot in without the white sleeve. It still counted, and I likely didn't lose any privacy, as Director of Elections Amber Reynolds told me.

That's because the second machine in the series automatically slices a side of the envelope and uses a suction cup to peel its sides slightly apart. An elections judge grabs the ballot, which is not marked with your name, while the outside of the envelope (which does have your name) is turned away from the judge.

The privacy sleeve is there as an extra protection in case this process goes awry.

“In fact, we prefer voters just to keep them. It’s less waste for us, less recycling for us," Reynolds said.

Next up: peer review.

Judges take the ballots and scan them en masse with a pretty standard piece of office equipment. The elections software reviews the markings, Scantron-style, but doesn't really count them. (That doesn't happen until Election Night.) Instead, the software is looking for unrecognizable marks, such as, say, a smiley face instead of a nice, dark oval.

Images of any of the unreadable ballots (including those with write-in votes) are then shot over to rows of judges -- again, bipartisan pairs -- who try to figure out what the voter meant.

This involves a lot of pointing.

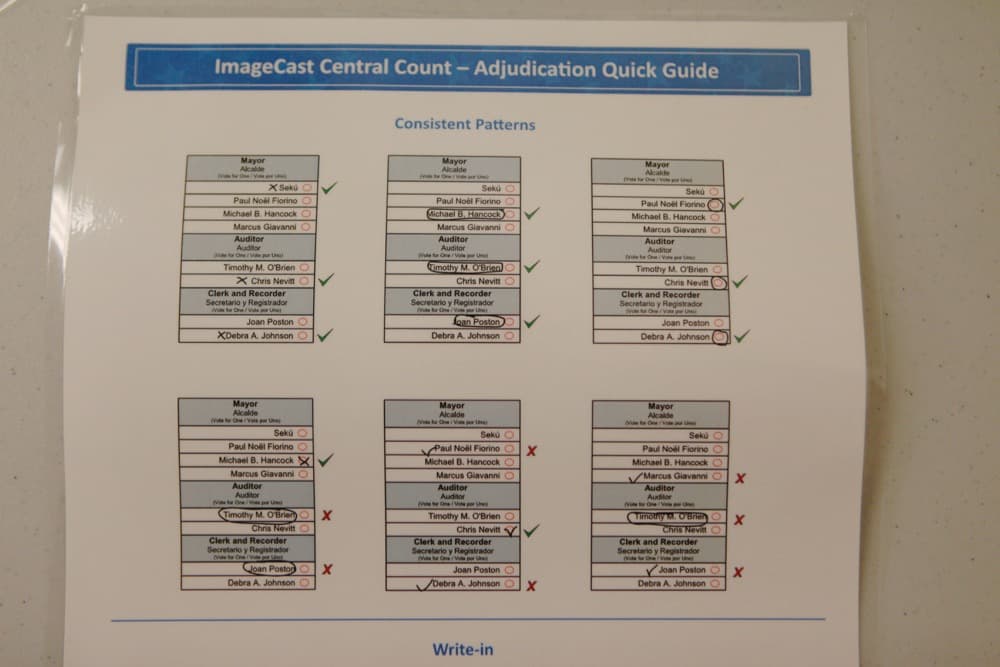

There's a whole set of weirdly fascinating rules about how they figure out what voters meant.

For example, if you used two different types of wrong markings, your choices can't be counted. If you're consistent in your renegade checkmarks, you'll still count.

The judges also interpret write-in votes. In Colorado, write-in votes only count if the candidate has filed the right paperwork. I saw one Bernie Sanders vote get rejected, because Bernie isn't trying to be the next president anymore.

Denver also piloted this software review system, which looked pretty painless to use. It used to be that the judges would have to review the physical ballot and then fill out a whole new ballot with the voter's intended choices.

This entire computer system, by the way, is isolated from the internet and the rest of the city network by an "air gap," meaning it's not plugged in by cables or wifi. The desktops also are rigged to shut down if anyone tries to insert a USB device. The effect is that it's a lot harder to get malicious software in the system.

No phones or devices are allowed at the stations, either.

There are about 700 judges in all.

They make from $11 to $15 an hour. They skew older, but certainly I saw a mix of ages and people.

The operation got fully underway on Monday. On Election Night at 7 p.m., the system will count up all those votes that have been processed and loaded.

Sadly, there's no giant button or lever. Just a click of the mouse and we'll fairly quickly know how Denver voted.