In Denver and beyond, arts communities and authorities alike have a major problem: How will they sustain arts communities in safe and affordable spaces?

When 36 people died in the Dec. 2 fire at Oakland’s Ghost Ship, it reverberated throughout every city where musicians fight to carve out spaces for themselves. Friends and family were lost in horrific circumstances, and while those wounds were still fresh, authorities around the country started shutting down DIY art spaces.

The first news came Dec. 5 from Baltimore, where housing and fire officials condemned the Bell Foundry, citing “numerous safety violations as well as deplorable conditions.” The space was a home, studio and performance venue.

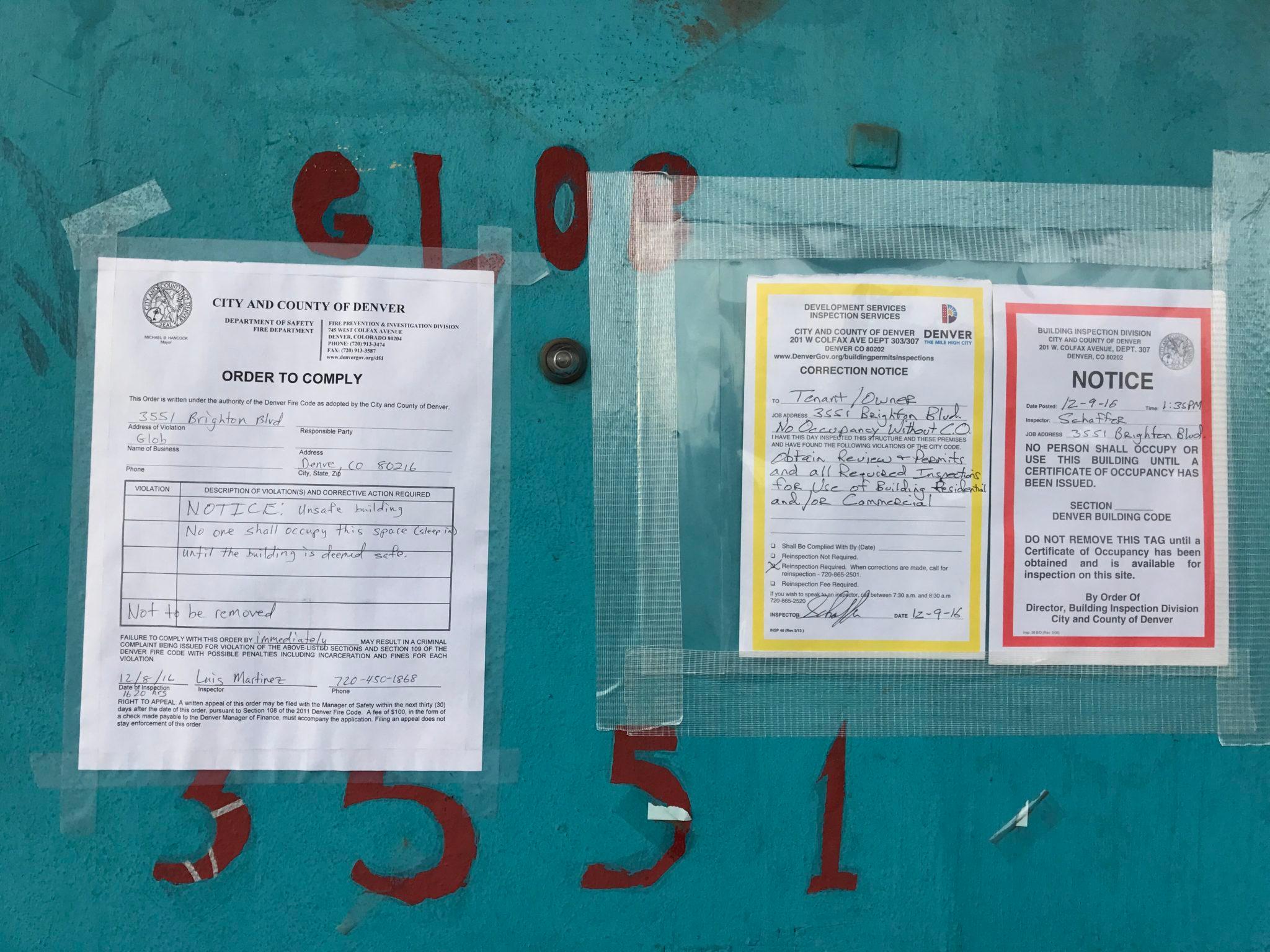

On Dec. 8, Denver took its own hit when the fire department performed a surprise inspection at Rhinoceropolis and Glob, sister DIY spots in an industrial space at 3551 and 3553 Brighton Boulevard. Five people were evicted on a freezing night because the building was not permitted as a residential space, which made its lack of smoke detectors and sprinklers an urgent issue for inspectors.

Current and former leaseholders and tenants at Rhino and Glob maintain that the fire department has been aware of their set up for all 11 years of their existence. Denver Fire Department spokeswoman Melissa Taylor has said that the city is already looking into similar spaces for safety issues, and people in Denver’s music community are hearing of similar crackdowns from friends in other cities.

Now, as artists rush to Rhino and Glob's defense, the people in power are trying to figure out what to do.

Places like Rhinoceropolis, Glob, Ghost Ship and the Bell Foundry are vital to the health of their cities’ arts scenes.

“People need to realize that it’s part of something bigger than itself,” said Isa Jones, a former Denver music journalist and the current arts and the entertainment coordinator for the Jackson Hole News & Guide. “Evicting five kids doesn’t seem like a big deal, but it has ripple effects through the community.”

To understand why, you need to know how a DIY art space works. They act as homes, studios and performance venues for local, usually young musicians and other artists. Sometimes they’re in warehouses, sometimes they’re just in regular houses. They take donations during shows to help pay rent, and they hold day jobs. They don’t typically sell alcohol (though people can BYOB) and all ages are welcome.

So if the five artists evicted from Rhino and Glob are out of a place to live, that means they’re also out of a place to create. Young artists generally don’t have the funds for both an apartment and studio space. They often barely have the funds for one of those things.

And it’s not just those five people who lose an important space. If Rhino and Glob aren’t hosting shows, that means new and experimental acts -- both local and touring -- are losing a place to play. Playing shows is the best way for a new band to grow and earn fans, and it's much harder to get booked at a “legit” venue if a band hasn't had a chance to grow that audience -- especially for bands that are bending rules and genres.

“The important thing to realize with all-ages DIY spaces is they facilitate local music scenes … it gives people a chance to develop as scene members.” said Michael Seman, the recently appointed Director of Creative Industries Research and Policy at CU Denver, himself a musician who has played many DIY venues.

Or as Kelly Maxwell, vocalist for local band Gora Gora Orkestar put it: “It’s almost like an incubator. It’s allowed to be messy, it’s allowed to be sloppy. You don’t get permission to workshop something on stage when people are paying.”

And while not everyone makes it far beyond those beginnings, many do. You might see them across town at the Hi-Dive, or you might see them a few years down the road, when the Ogden Theatre is just one stop on a national tour. Future Islands, Dan Deacon, Crystal Castles, Matt & Kim, Thee Oh Sees and Lightning Bolt -- though they don’t call Denver home -- played early shows at Rhino and Glob.

“You can’t build a local scene if you don’t a have a space for them to build their art,” Jones said. “You need to give them a safe space.”

If you’re talking about DIY, you’ll hear those words a lot.

The idea of a safe space has lately been associated with college campuses and often is mocked by people who think America is becoming too politically correct. For artists, though, a "safe space" often means an inclusive and accessible place. Rhino, Glob and other DIY art spaces in Denver and elsewhere are almost always all-ages and tend to work harder than “legit” venues to give a stage to underrepresented groups.

This past year, Glob hosted Titwrench Festival, a multi-day showcase of art and music made by women and LGBTQ artists. Rhino hosted the event in 2009.

Sarah Slater, co-founder and music director of Titwrench Collective, said venues offer a way to put on the festival without much money and make it accessible to more people that it would be if we were at, say, an AEG-owned venue.

“I think one of the main [reasons DIY is important] is that it’s just the way all-ages spaces for all music and art -- live music particularly -- are rare in our city, and it’s a completely different environment to experience music in than an expensive bar or place where the cover might be $20 versus a $5 donation,” she said.

“I think it’s an issue of accessibility for people from all different underserved and marginalized communities that don’t feel welcome or safe in night clubs or bars or places they can’t get into because of their age or might not want to go to because they just don’t feel welcome. And I think Rhino and Glob have both … worked hard to make those places focused around building community.”

And that’s just as important to fans as it is to artists.

“They just are places that really provide something really valuable to our culture -- places where people can experience challenging and new art forms, experimental forms of music and beauty,” Slater said. “I think they’re really vital to our city. For a lot of young people, that could be their entry point in participating in the arts scene.”

When Jones was an under-21 student at CU, for example, she was missing out on shows at places like the Larimer Lounge and the Hi-Dive. But at Rhino, she could (and did) see STRFKR, Ty Segall and Mikal Cronin.

Anna Stein, a local artist and fan, told Denverite in an email, “DIY spaces allow teens to see art and music because they heavily push forth that you don't need to be a certain age to experience music and art. Rhino allows a space for people to feel accepted and showed them they too can create. These spaces give people the strength to be who they want to be, and that's what makes DIY so important and beautiful.”

Now artists are struggling to hold onto those spaces.

Denver and Oakland share the same problem: Artists are being priced out of the neighborhoods they made cool. As Seman points out, these cities have less and less cheap real estate all the time, which means artists are running out of options each time they’re driven out of a building or neighborhood.

In RiNo -- a neighborhood name many in this scene reject and which has no connection to the Rhinoceropolis name -- development is booming and already poses a very real threat to the existence of Rhino and Glob.

“You call it an art district, which seems like a slap in the face almost,” said Maxwell, who lives in the area. “If you can’t have artists live in the space you call an arts district, what’s the point? They’re displacing artists left and right.”

“It’s so important to value the thing you say you value,” she added, “because without them we’re kind of just a husk with legal weed.”

It's a common sentiment among Denver artists, some of whom feel the city uses the art scene as a marketing tool but does not effectively support it. Slater and Jones both brought up the issue, noting that neither of them has heard a city official or big player in the music scene speak up in defense of Rhino or Glob.

Seman says part of the problem is how difficult it can be for a city to get anything done. They’re “large organizations,” and what’s important to one department might not be important to the others. But Denver knows what his research shows -- that a good arts scene attracts people, and people drive the economy.

“The thing that’s unique about Denver is it’s happening very quickly,” he said.

“When [the evictions] happened, I was immediately texting, messaging, emailing,” he added. “My contacts in the city, they know the value of Rhinoceropolis. It’s just that they’re trying to address it with the speed of a city.”

So what needs to be done to protect the music community’s roots?

It’s called DIY for a reason, but in the face of rapid development some cities are asking themselves how to keep small art spaces open.

Oakland has already made a big, showy move to defend DIY. On Dec. 7, Mayor Libby Schaaf announced a $1.7 million investment to “support sustainable, long-term solutions to creating affordable, safe spaces for Oakland’s artists and arts organizations,” Pitchfork reports. The city’s Community Arts Stabilization Trust will receive funding from two different foundations to acquire real estate for those safe spaces and to save at-risk arts organizations. They’ve been working on the initiative for months, but it became more of a priority after the Ghost Ship fire.

After the Rhino evictions, the RiNo Art District released a statement making a commitment to DIY art spaces and outlining a loose plan. Here it is in full:

1. We are committed to working with Rhinoceropolis, the property owner, Denver Fire Department and Denver Police Department and the city of Denver to reopen Rhinoceropolis as a music venue as soon as possible.

2. We will be re-looking at zoning of former industrial buildings in our neighborhood, such as the one Rhinoceropolis calls home, to identify how we can make amendments to allow for utilizing these affordable spaces as live/work places for our artist community in a safe way.

3. With urgency, we will be continuing our conversation with the city about the importance of artist-run spaces and what we all can do to help ensure they continue to exist, in a safe, but affordable way so that our artists can live and create in our urban core. Shutting things down is not a solution. Working together, creatively, to address safety issues while allowing creative uses… is.

In an interview with Denverite, RiNo Art District President Jamie Licko expressed frustration at being perceived as too corporate or too close to the city.

"The minute we start losing our creative space, we've lost our culture as a city … The minute you start pricing people out, you lose your soul," she said.

"If anything, we hammer the city on a daily basis about doing things differently. This is a neighborhood that created a special district to support the art district, and we invest that money back into special projects."

Council President Albus Brooks said he considers it vitally important to keep these vibrant artistic communities and for people to stay in RiNo, noting that the development going in at 38th and Blake will have affordable artists space.

He also said he will "put his money where his mouth is" in terms of both policy and city subsidies if necessary.

What any of this will amount to remains to be seen.

Right now, the effort to get Rhino and Glob back open for shows remains thoroughly DIY, short of support from property owner Larry Burgess. A supporter has already made a GoFundMe page, which Rhino and Glob leaseholder John Gross has assured people is trustworthy. It was created Dec. 9 with a fundraising goal of $10,000. As of about 1 p.m. on Dec. 12, it had raised $12,300 from 322 people.

Seman thinks DIY spaces should consider finding ways to move a little closer to legitimacy, perhaps by becoming 501(c)(3)s or partnering with an existing organization that’s 501(c)(3) -- “moving into the realm of donors who appreciate their value in the arts.”

He pointed to Santa Fe’s Meow Wolf as a good example: “They have a pretty sophisticated structure. We’re not talking about direct influence by the city, but they can exist in a framework that’s a little more legitimate.”

What is clear to many artists that something substantial needs to be done now, for the sake of the roots of Denver's arts.

“Anyone that cares about the arts who’s in a position of power needs to speak out and this is the moment to do it,” Slater said. “It can’t really wait.”