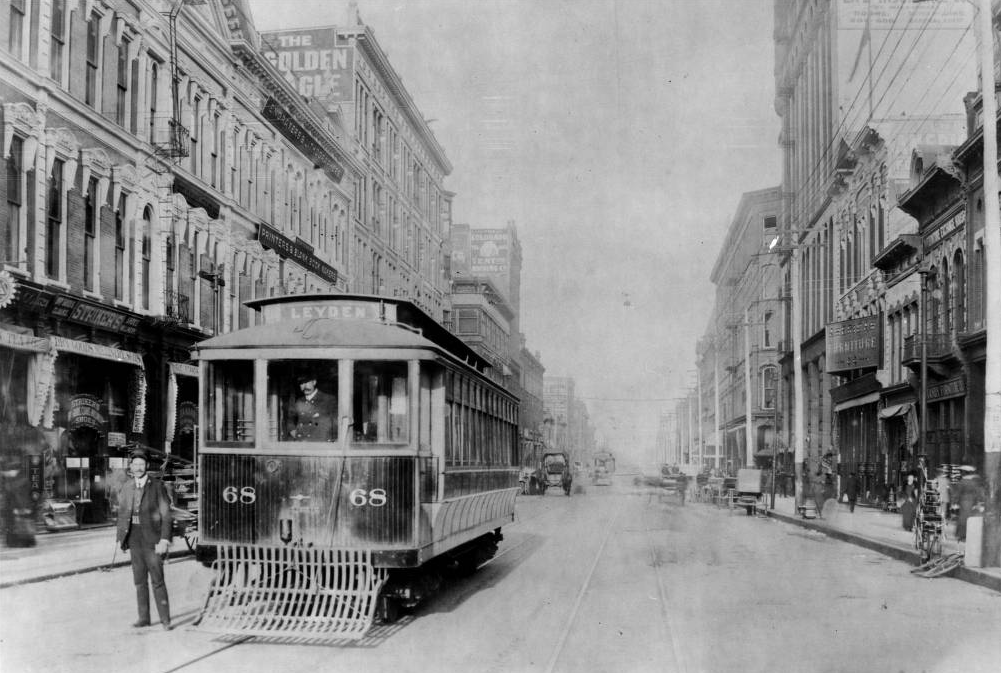

The miniature commercial districts outside of downtown Denver can seem to appear out of nowhere.

In Platt Park, a turn from residential lanes onto Pearl Street reveals a long stretch of tight-packed brick buildings and local staples from Sushi Den to Kaos Pizzeria. In the northwest, the Tennyson Street district lances through blocks of lawns and cottages.

Ryan Keeney has a theory about why these beloved strips are where they are: It's all about the old streetcar lines.

As a recent master's graduate from the University of Denver, he has spent hours reconstructing the exact routes of the trolley lines that once crisscrossed Denver on rails embedded in the street.

At their peak, they had more mileage and vehicles than RTD's modern rail system. And, according to Keeney's analysis, it was this system that planted the random pockets of density that Denver treasures today.

"If you ever see a nice pedestrian oriented kind of commercial building … flush to the sidewalk, without a parking setback, odds are, there’s probably a streetcar that ran right past its front door," Keeney said.

First, let's check out the map that Keeney compiled.

This represents every line that existed in Denver. Not all of them existed at the same time. To see how the system grew, use the blue clock icon.

As you can see, the lines covered much of central Denver, even stretching as far as Wheat Ridge, Englewood and Lakewood.

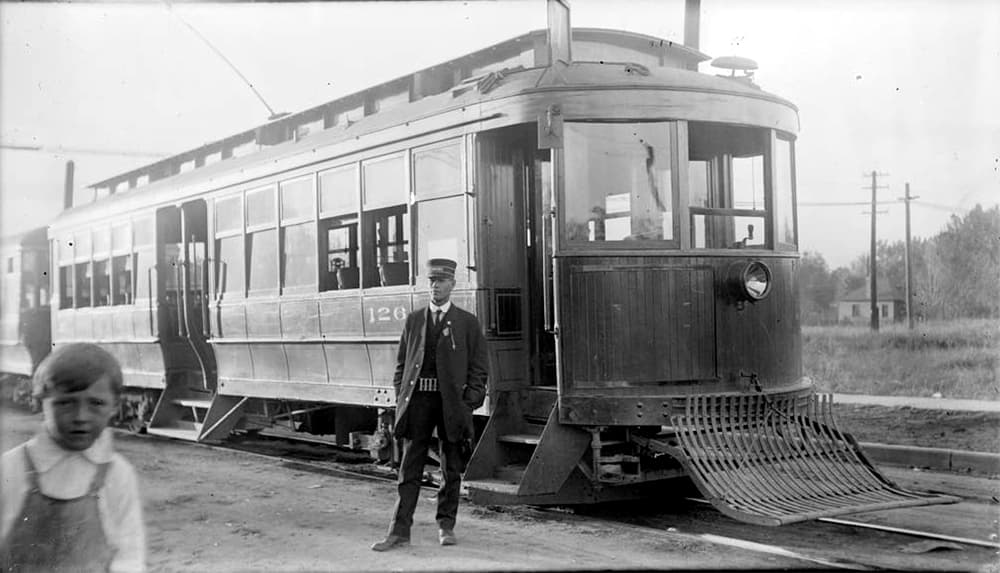

Denver's streetcars originally were pulled by horses. Later, they trundled along by gripping moving cables, then by steam engines and eventually under electric wires that were webbed over the streets. They were an early form of urban mass transit, available at a time when relatively few people had access to any reliable means of transportation.

Unsurprisingly, the city grew around the streetcars.

"It was walking and the streetcar, pretty much, unless you were rich enough to have a horse," Keeney said of the early days. "The city fabric was pretty tightly bound through the streetcar line."

The streetcar lines allowed the city to spread its suburban wings -- some of the first waves of new neighborhoods were called "streetcar suburbs" -- but the routes still attracted people to concentrated areas, allowing these commercial strips to prosper, Keeney said.

That seems to make intuitive sense -- in fact, the theory was suggested to Keeney by a city planner as a topic for his capstone project, which it eventually became. But the graduate student wanted to take it further, so he dug through city records in painstaking detail, breaking down what he calls "streetcar neighborhood commercial developments."

You can see his classifications in the second section of his online capstone presentation. Keeney also zoomed in on two of those districts and found that the denser development encouraged by the streetcar route seems to have made the area more walkable today.

Keeney calculated that the system peaked around 1917, when there were just a few thousand automobiles in Denver. The streetcars died out over the decades before and during World War II, done in by the popularity of the car and suburban growth that leapfrogged past the system's edges.

Public opinion of the system also turned negative, especially because of the fact that they ran through residential areas. "These are these old, obsolete noisy things. They’re disturbing the peace, the rails were squeaky," Keeney said, recounting measures of public perception that he reviewed.

There have been pushes here and there to revive the streetcar in Denver, perhaps along Colfax or through downtown. None of that seems particularly likely. For one, the influential transit consultant Jarrett Walker argues that buses are just as fast as streetcars, since both use essentially the same kind of infrastructure -- the street. On East Colfax, it's looking more likely that the city will pursue bus-rapid transit instead.

But there may still be some lessons to be learned from the streetcar system. Keeney looks at places like Tennyson and Pearl as miniature versions of "transit-oriented development," the city-planning term for the new clusters of apartment buildings and retail around some of the city's new rail stations.