The motels that line Colfax are faded remnants of the avenue's glory days, vital housing for people who might otherwise be living on the streets or in their cars and havens for prostitution and drugs.

Tom Fesing, past president and board member at-large of the East Colfax Neighborhood Association, is keenly interested in the revitalization of the corridor and desperate for city officials to take a harder stance.

“I’d like the city attorney to take a hard look at bringing a public nuisance case against one of these motels," Fesing said. “Every time they do (a motel raid) in our area, they take six or seven guns from convicted felons living in these hotels. ... A lot of them are infested with bedbugs. There’s safety issues whether that’s fire alarms, mold, that’s just not healthy.”

Ashley Angel landed in a Colfax motel after escaping an abusive relationship with a baby and a toddler in tow. Her next door neighbor is a veteran of the Vietnam War who lives on disability. She's painfully aware of the limitations of motel life, but it's what she can afford for now.

"Shelters are already full, and if they shut down all the motels on Colfax, the cheap motels that people can afford, there’s going to be a lot more people on the street," she said. "If it wasn’t for this place, my family and I would be on the street."

This is the complicated landscape that city inspectors, planning officials, social service agencies, neighborhood activists and hundreds of poor individuals and families -- many of them working full-time but at low-income jobs, many others living on disability checks -- must navigate as new eyes and new investment turn toward Colfax.

For all the speculation about the corridor's future in general and the fate of its motels in particular, there doesn't seem to be a lot of immediate redevelopment pressure.

When motels change hands, they generally continue to function as motels.

None of the cities along the corridor -- not Denver, not Lakewood, not Aurora -- are in a rush to buy them up, though the idea gets batted around from time to time.

“Redeveloping it is a challenge because the motels are very lucrative," said Monica Martinez of the Fax Partnership. "They charge $60 a night, cash business. They don’t have to put a lot of investment in the properties.

“If the city wants to see these properties redeveloped and recognizes that they are affordable housing of last resort that is bad housing -- there’s no social services component, and the quality of the housing is low -- they will have to move the hand of the market, and that might be a straight-out purchase.”

Lakewood Deputy City Manager Nanette Neelan, who is also the city's economic development director, said residents and community groups occasionally approach the city about buying up Colfax motels, but the city has never had the resources to do so. Aurora Housing Authority Executive Director Craig Maraschky said that while he's heard "very offhand comments" about buying and redeveloping motels as affordable housing, he's not sure it makes sense.

"The challenge is you have to pay the market rate, so some huge subsidies would be needed," he said. And then what you'd have would be micro-units, many with no kitchens, not the type of housing the authority typically builds or manages.

"It would cost a lot of money for the rehabilitation," Maraschky said. "They would need a lot of upgrades, and is that the best use of the resource?"

Erik Soliván, director of Denver's Office of HOPE, which oversees housing policy, said the city is taking a hard look at how it can support and improve what motels offer today -- Denver has been approached specifically about the shuttered Royal Palace Motel right off Colfax on Colorado Boulevard -- and the city is asking some of the same questions as Aurora.

On the one hand, a new unit of affordable housing costs roughly $250,000 to build, so rehabilitated motel rooms could be brought on line much faster and almost certainly cheaper. On the other hand, you have very small units, perhaps with no kitchen, perhaps without their own bathrooms, maybe with asbestos, maybe with mold -- it gets complicated fast.

Meanwhile, authorities in Denver and Aurora have increased the frequency of inspections at motels, and Denver's Motel Task Force just this week brought its first nuisance abatement case in years against the 7 Star Motel, 8400 E. Colfax. Conditions there were considered bad enough that Denver wouldn't allow the motel vouchers it gives to homeless people to be used there, and just in the first nine months of the year, there were more than 100 calls for police at the 7 Star, according to City Attorney Kristin Bronson. A show-cause hearing to suspend or revoke the motel's license is scheduled for mid-November.

Bronson said the city gives motel owners a lot of chances to fix bad conditions and crime problems. Sometimes a change in ownership thwarts enforcement efforts by requiring that the process start over, but there's a reason the city is cautious.

"It's a thoughtful and measured approach," Bronson said. "This is not only people's businesses and livelihoods. It's often people's homes."

It wasn't always like this.

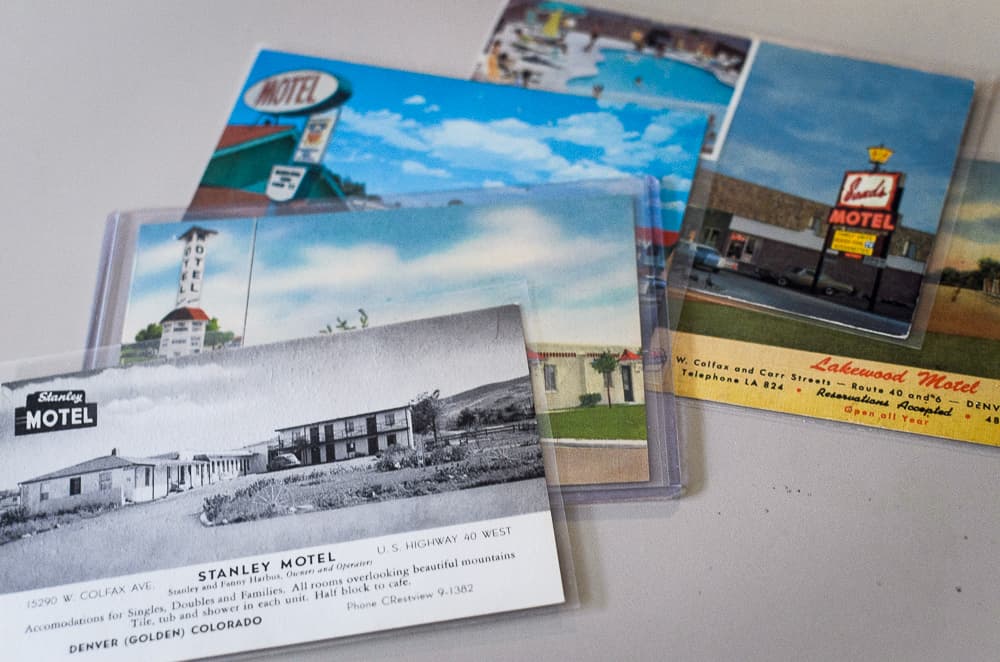

Jonny Barber, Colfax's unofficial lay historian, has collected thousands of motel and hotel postcards from the strip's heyday. (You can see some of them on his site, ColfaxAvenue.com.) They depict a verdant corridor lined with trees and facilities trying to outdo each other with the most modern amenities.

"There was a lot of tourist traffic," he said. "Highway 40 was the most traveled highway coast to coast. All Route 66 had on Route 40 was a better PR guy and a song."

The generally agreed upon version of events is that the construction of Interstate 70 dealt a death blow to Colfax from which it never recovered. Moving the airport from Stapleton just twisted the knife.

"These motels were all really nice. People were trying to outdo each other. It was like Motel Wars for a while," Barber said. "What do you do when you have this strip like Disneyland and you don't have any more tourists? ... What else are you going to do with a motel? You have to rent rooms."

As documented in postcards and property records, there were once more than 200 motels, hotels and lodges along Colfax in Aurora, Denver and Lakewood, beckoning to cross-country travelers on U.S. 40. In a recent drive down Colfax, I counted a little more than 60 motels and hotels, including higher end establishments like the Holiday Chalet and some more formally converted to long-term housing, like the Argonaut Apartments and the Golden Manor assisted living facility, which was once the Four Winds Motel.

Angel is convinced that the powers that be want the motels gone, to see the properties redeveloped. Denver has no specific zoning provisions that would encourage the redevelopment of motels or their retention, though the "main street" zone that governs land use along most of Colfax would allow for denser development than what is currently represented by motels.

Denver is in the process of doing an East Area Plan and an East Central Area Plan, both of which include the Colfax corridor.

Curt Upton, a principal city planner with the city of Denver, expects that these plans -- currently in the visioning stage during which planners listen to community members -- will make some suggestions for motel sites, but he's not sure yet what that will be. People who live along the corridor had a lot to say about motels in community meetings, but there was little consensus.

"There are some people who view those motels as a nuisance, and it's hard to pinpoint what the issue is," he said. "People associate those motels or that part of the Colfax corridor as having a crime problem, whether it's drugs or prostitution or violent crime, that they associate with the motels. Other folks we've heard from say that even though it's not obvious, these motels have this great place-making, iconic quality. It would be great to fix these properties up and maybe repurpose them with different uses or even keep their motel uses.

"There is value in this mid-century Googie architecture, the vintage signs, this auto-era design. People also value these motels as assets."

Any proposal to demolish a motel in Denver would require a review for historical significance before a permit would be issued, but preserving historic elements doesn't mean keeping motels as housing. One example is the Metlo on Broadway, where coffee shops, nail salons and offices operate in what were once bedrooms. The building retains the classic sign and retro feel of a motel in a very different context.

That's pretty cool, but what would happen to the people who live in motels if redevelopment took that route?

A crisis earlier this year at the King's Inn Motel in Aurora revealed just how vulnerable these residents are but also kickstarted an effort to help people find much more stable housing.

The King's Inn is where Angel landed with her children when she returned from Las Vegas to the Denver metro area, where she has family and a support network. She paid $240 a week for a two-bedroom unit. It was not a nice place, by any means. There were cockroaches and bedbugs and the floors felt like they might give way when you walked on them -- "it should be condemned!" is how she described the King's Inn -- but she could afford it and her unit had a kitchen.

Then new owners raised the rent to $525 a week and started evicting and threatening residents, Angel said.

Angel called up Colorado 9 to 5, an advocacy group, because she had previously taken a renters' rights workshop with them, and they, along with the Colfax Community Network, helped residents organize. The rent eventually came down to $420 a week, but it was still too much for most.

Shelley McKittrick, Aurora's homeless program director, said the King's Inn was an education for her, even after years working in social services.

"I was hoping those folks were not as vulnerable as they are," she said.

In California, where McKittrick previous worked, renters who stay somewhere longer than 30 days accrue all the rights of renters with leases, including protection for sudden rent increases and evictions. Motel residents never get those protections in Colorado, even if they've lived somewhere for a decade or more, as some denizens of the Colfax motels have.

Many motel residents are paying as much or more than people with regular apartments or even mortgages, but they can't save up enough to pay first month's rent and security deposit or their income is irregular. Others have criminal convictions or evictions on their record, and in Colorado, unlike many states, there is no limit to how far back a landlord can look. In a tight rental market, something you did 20 years ago can prevent you from renting an apartment.

Who are the residents of motels? McKittrick describes some of the people she's met. Mothers fleeing abusive relationships with their children. People on disability. A retired bus driver. Older women who should be retired but still work full-time because they have to.

"They’re living in a dive, and they’re cleaning nice hotels," McKittrick said of these women.

As the problems at the King's Inn came to light -- the poor conditions coupled with the lack of any tenant protections, Aurora faced the prospect of dozens of newly homeless families and individuals. The Aurora City Council allocated first $40,000, then $80,000 in flexible housing funds that have helped 40 households from the King's Inn find stable housing. For 20 to 30 percent of the households, the only barrier to housing was the move-in funds.

For others, they needed larger deposits to convince landlords to overlook criminal histories or past evictions -- Aurora works hard to recruit open-minded landlords for this. In a few cases, the money helped families move back to where they have more social support. One family is living happily in a five-bedroom house in Missouri for $600 a month. But most stayed in Aurora and most are paying rents between $825 and $1,200 a month -- less than they were paying to stay in a motel. Denver is also looking at how it can keep better track of who is staying in motels to connect people who are eligible with more stable housing.

Some of the most grateful recipients of this assistance have been single, able-bodied men who work at low-wage jobs.

"The single men would say, 'You can help us? We never qualified for anything,'” McKittrick said.

Seeing the success of this investment in moving people into better housing, the city allocated another $200,000 in flexible housing assistance. With that money, McKittrick is able to work with people beyond the original group from the King's Inn -- for example, helping a homeless man who just got a job get into an apartment right away so he doesn't lose his job while he tries to save for a deposit.

And the King's Inn seems to be in better hands, McKittrick said. After all the negative publicity, the partnership that bought it had another member take on day-to-day management and rents have come down to $35 a night, lower than many Colfax motels. There's still a lot of work to do -- "the bedbugs and mold have to go" -- but McKittrick thinks it might even become a positive actor in the community.

Angel is still living in motels, though she hopes for not much longer.

From the King's Inn, she moved to the Carriage Motor Inn, where she now pays $380 a week, roughly $1,700 a month, for a two-bedroom unit. There's no kitchen in the units at the Carriage Motor Inn, so meals are cooked in the microwave and dishes are washed in the bathtub.

On the morning that I visit, 2 1/2-year-old Kayden and 15-month-old Sadia snack on plain ramen noodles while cartoons play on the television and clamber on their mother's lap for attention. On a neat shelf in one corner, there's a complete set of the Harry Potter and Narnia books.

"You have to worry about your crazies that come and go, your druggies, your prostitutes. It’s not easy living in motels, especially when you have kids," Angel said. Early in her stay here, there was a police raid announced with a bang and officers pouring out of two white vans, and she ducked inside with her children. She's a light sleeper, and she's always getting up to investigate every noise and make sure her family is safe. Sometimes fights behind the motel wake up the kids, who sleep in the back bedroom.

But the owners are nice and work with her if she doesn't have all the money on Thursday, when rent is due, and she thinks they're trying hard to clean the place up.

Angel is working with McKittrick, and she hopes to move into an apartment soon, maybe even by the end of the month. Her fiancé has a new job doing construction clean-up downtown, and she's feeling more ready to look for work herself, thanks to a program through the Center for Work Education and Employment.

This more optimistic outlook comes after a low point this summer when Angel had to panhandle to make rent for three weeks.

"That hurt," she said. "I never thought I would be in that situation. I always told them that I was going to work because I couldn’t let them see me like this."

As much as Angel is looking forward to closing the motel chapter of her life, she worries about what will happen to other people if this stops being an option, and she wants others to know that many motel residents are hard-working people making the best of a bad situation.

"Just because people live in motels shouldn’t mean they’re judged by where they live," she said. "We’re all humans. Some of us don’t have the life that other people have. We have to do what we can to survive. ... If people would understand how much motels actually do help, then maybe they would change their thought process about these places. Yeah, they may look run down, but it’s home. We make it work."

Angel confesses that many motel residents are scared to make complaints about unsafe conditions for fear that their last refuge will be shut down. McKittrick said motel residents also end up in complicated kinds of debt to their landlords, for example by doing unpaid work in exchange for cheaper rent. These obligations leave them even more vulnerable.

Bronson, Denver's city attorney, said this very vulnerability is why consistent enforcement is necessary: "The city has an obligation to bring them into compliance because vulnerable people are living there."

"The dream across the metro region with these motels would be that we would get these bought by non-profit organizations or for-profit developers who have an interest in working with folks and redevelop them," McKittrick said. "My dream is to transform them into something that does not create more vulnerability but gives people a chance to get on their feet."

That's exactly what Volunteers of America has done since 2001 at the former Aristocrat Motor Hotel on West Colfax.

Volunteers of America for decades has worked with homeless women and children. In their Brandon Center shelter, workers heard "horror stories" about motels from the people who sought their help, said Dianna Kunz, president and CEO of the service organization.

"You said housing of last resort, but for the shelter community, they're first resort to get people off the street," Kunz said.

Denver at that time was spending $500,000 a year on motel vouchers, but the people who got them weren't able to use that opportunity to turn things around.

"What would happen is that families would get a motel voucher and they would be so relieved to finally not be on the street that they would kind of freeze in place and get stuck," Kunz said. "They would be so glad and so tired that they wouldn't take that next step. Their time would be up, and they wouldn't have made any progress in connecting with services or getting in touch with family."

Volunteers of America approached the city with a plan: The organization would buy a motel, fix it up and maintain it to "Motel 6 standards." Denver Human Services would have case managers on site to work with residents, who stay anywhere from a few days to two weeks.

Thus was born the 45-room Volunteers of America Family Motel.

"It's a motel, but it's not a motel," Kunz said. "You have to be actively working on your issues."

A stay comes with a free continental breakfast and snacks and fruit all day long, so the kids never have to go hungry. Case managers help residents sign up for the services for which they are eligible and find a more stable housing situation.

The motel serves families with children, single women, adults with disabilities, veterans, runaway teenagers. There are also 20 respite beds for homeless people who are ready to leave the hospital but have nowhere to stay while they recover, and those folks get three meals a day.

It's proved more challenging than Kunz expected to keep the place to the appropriate standards. The large majority of residents treat the place with respect, but with people moving in and out all the time and some of those people having a range of problems and 45 separate units with 45 separate bathrooms, things break and get broken. The remodel was extensive -- "down to the studs" -- and there's still a mortgage payment from the purchase. It costs about $31 per day per unit to keep it running.

"It is expensive, but I don't know what isn't," Kunz said. Helping vulnerable people costs money no matter how you do it, and the challenges are balanced by some real benefits to the motel environment.

"The beauty of it is that families do have their own private space, and that increases their feeling of security," Kunz said.

And there isn't the stigma that attaches to shelters.

"People understand motels," Kunz said. "People are ready to go there. The family stays together, there is security, you keep track of your own belongings. ... It makes a lot of difference to the families when they check in, and it looks like Motel 6."

The old Aristocrat sign still hangs over the Volunteers of America Family Motel. The neon is hard to maintain, and it is "a bit of a misnomer," Kunz said.

"The architect convinced me we would be ripping the heart out of Denver if we took that sign down," she said.

Andrew Kenney contributed reporting to this story.