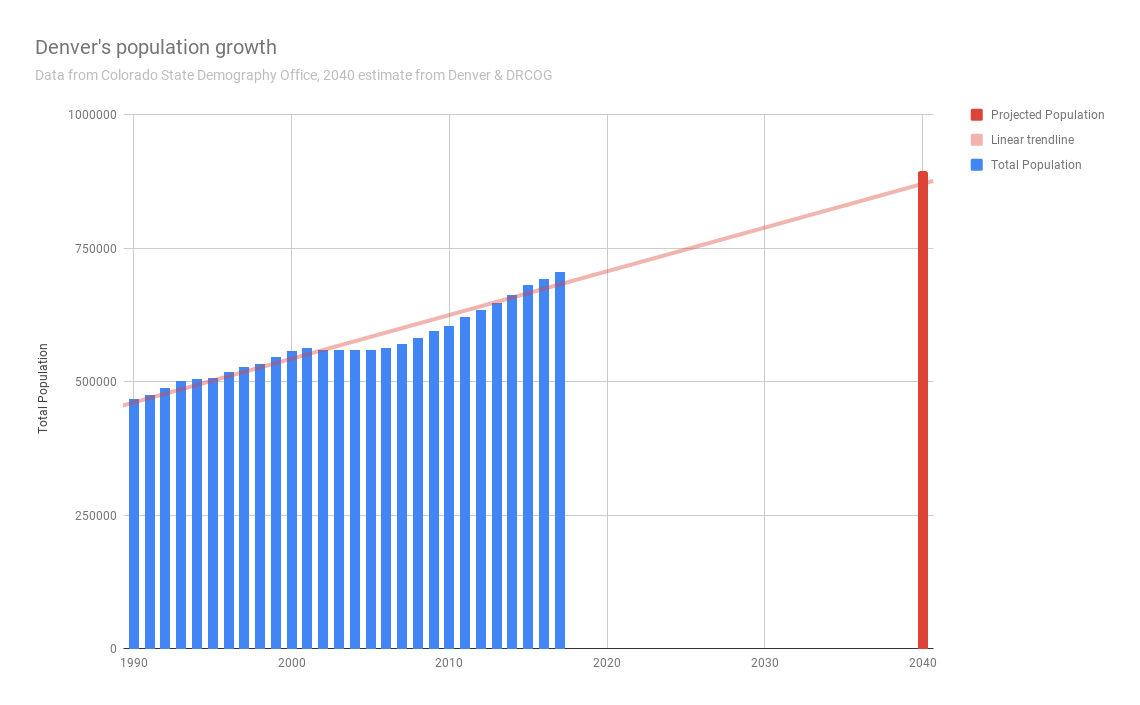

In 2040, nearly 900,000 people could live in Denver.

That's the assumption behind a far-reaching set of plans that the city government introduced this morning. Together, they represent the government's strategies for its next 22 years of growth, covering parks, transit and development.

The figure at the heart of all this -- 894,000 residents -- would represent a 21 percent expansion of Denver's population.

“The reality is, this is our forecast and our projection. We don’t know to what level we will accomplish our forecasted numbers,” Mayor Michael Hancock said in an interview. “Our responsibility today is to plan for the future.”

The exact number will change with inevitable booms and busts. But the projection is part of a vision that will undergird Denver's decisions in the decades to come. Known as Denveright, these new strategies include broad ideas as well as detailed recommendations for the city's streets, transit systems, parks and development.

This is Denver's first unified update to its overall city plans in nearly two decades. These new strategies are built around an assumption that Denver's population will continue growing at roughly the same pace as it has over those 20 years.

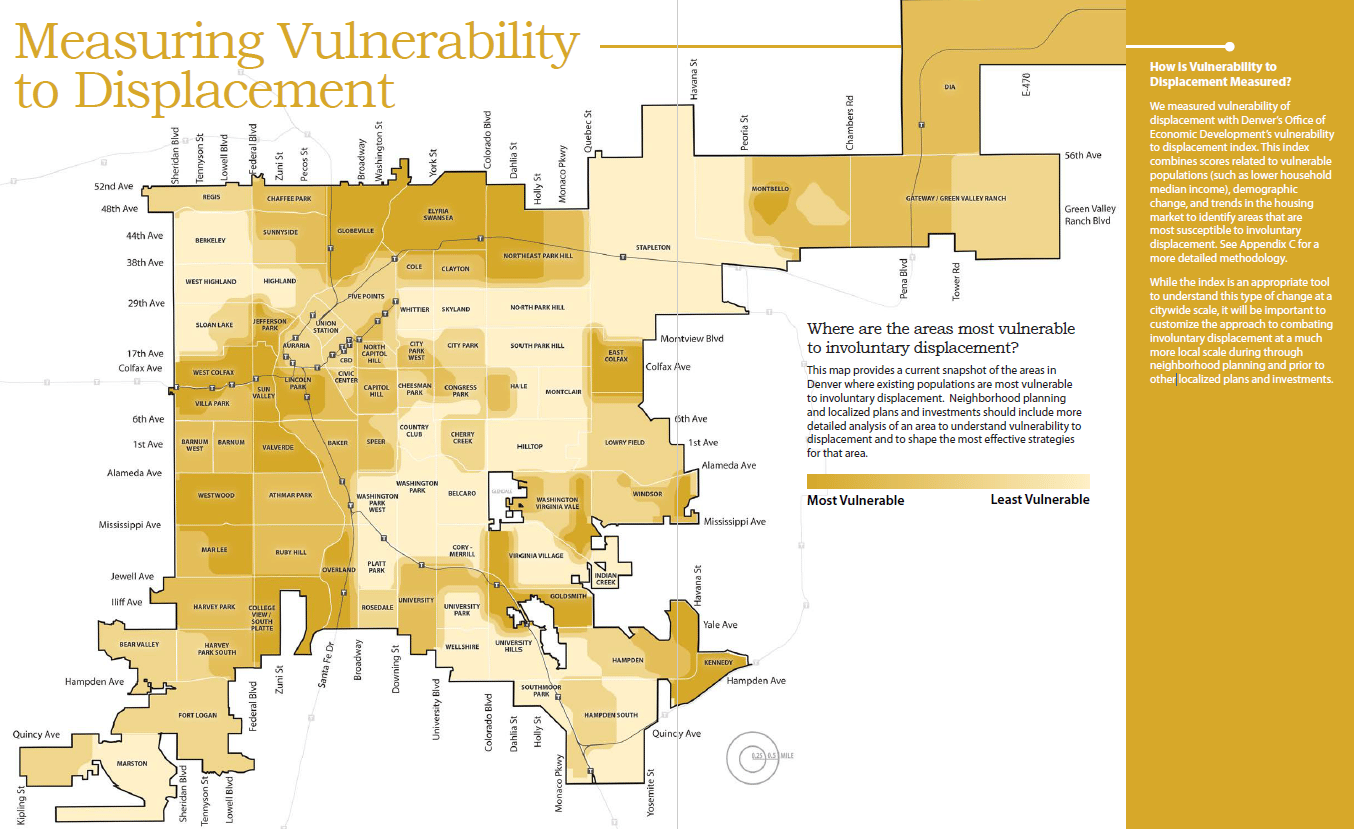

Today, the city has nearly filled out all of the available open space within its borders, and it's surrounded by fast-developing neighbor cities and suburbs. High housing prices have forced countless residents from their homes.

Meanwhile, the city's builders have turned their focus to redevelopment -- whether they're building condos in residential neighborhoods or planning new urban districts on former industrial sites and even Elitch Gardens.

With those new challenges in mind, the plans outline how and where Denver will grow. They try to funnel new development into dense urban centers and along busy corridors, which could be upgraded with new transit services. They call for new architecture rules that could stop the next annoying architectural style, such as slot homes. And they introduce new ideas about social justice and equity.

“It’s a waste of time to focus on whether we can stop growth. What you do is ask whether you can plan for growth responsibly," Hancock said when asked about the assumptions of new development in the plan.

“There’s anti-growth sentiment all over the nation. ... I think what people are most concerned about is their quality of life and the uniqueness of the neighborhood.”

Of course, it's all hypothetical for now. The plans represent the vision and philosophy of Mayor Michael Hancock and his administration. They don't guarantee that anything will be done -- instead, that depends on the Denver City Council and the mayor's future actions.

So, here's what we know.

Transit.

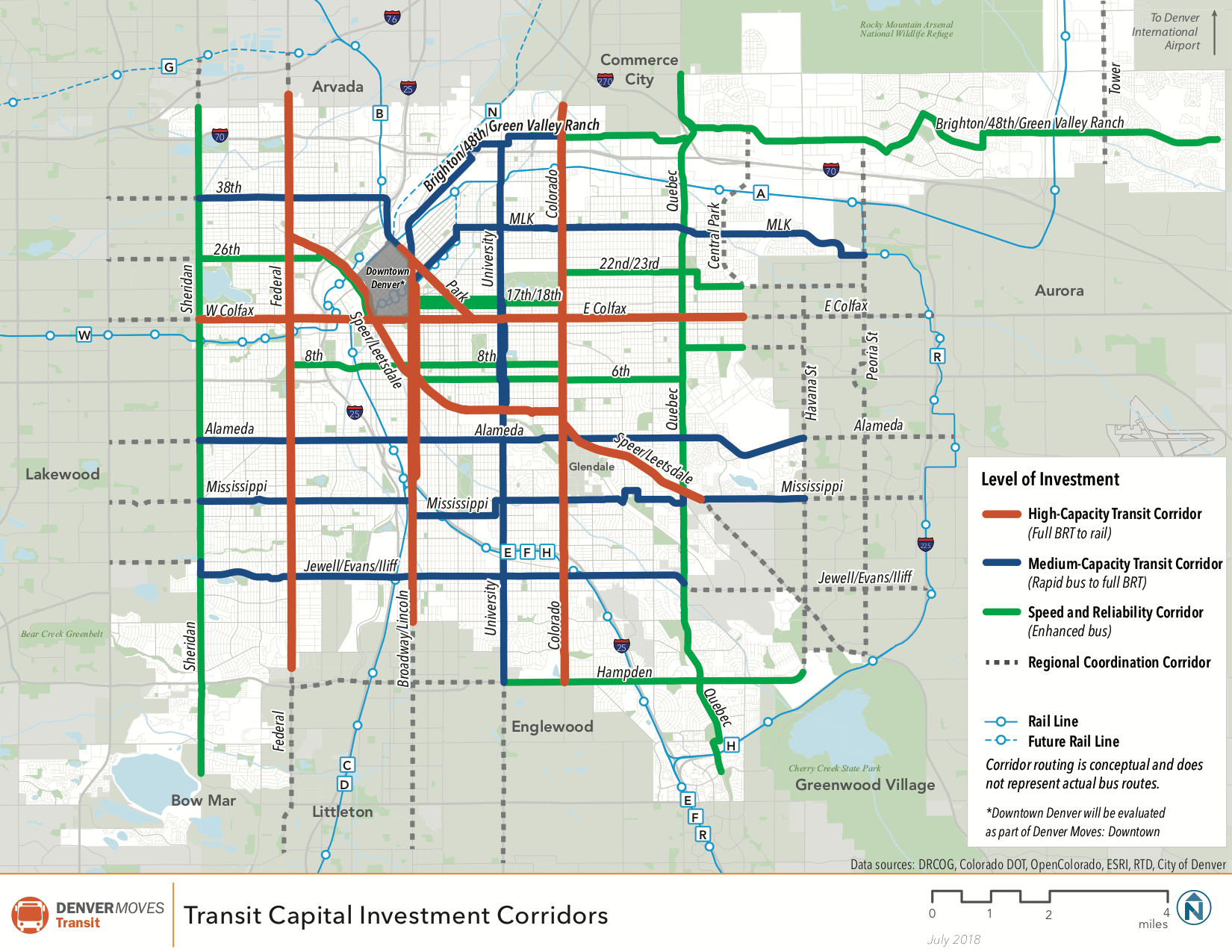

The new "Denver Moves" plan calls for the city to strengthen its transit system along key corridors. They represent the city's "first ever city-wide transit plans," said Eulois Cleckley, the new head of the Department Public Works.

"There's going to be a higher demand on alternative transportation modes, and transit is truly the great equalizer," he said, referring to a goal of allowing all people to get around "without having to rely on their vehicles."

The strongest focus would be along Federal, Broadway, Colorado and Colfax and Speer for "high-capacity" transit, but the city has identified 19 corridors in all.

Right now, only three of the city's bus lines meet Denver's new "frequent transit" standards, with buses arriving at least every 15 minutes. The new vision calls for 75 percent of all households and jobs to be within a quarter-mile of a high-frequency line.

"Anytime you increase the frequency, you're going to increase the attractiveness of that mode," Cleckley said.

That would take some spending. The plans lay out options ranging from $1 billion to $5 billion. At the highest end, the city envisions building out six rail corridors and seven new BRT lines. Of course, RTD doesn't have that kind of money in its accounts.

The biggest question will be whether the city attempts to launch its own transportation department -- a plan that may be looking more attractive as RTD looks at service cuts and fare hikes.

"This is an aspirational plan, first. We want to be bold in setting the vision first for transit," Cleckley said. "There's definitely a recognition that RTD may not be in the best position to provide all of the bold recommendations in this plan." We could learn more about that toward the end of the year, he said.

Separately, the mayor said that new transit districts could be created. He currently has a group working “to identify a pathway forward toward a more sustainable funding source for the city of Denver,” with a goal of minimizing the cost to residents while guaranteeing a “healthy investment."

“Outside of housing, there is no greater need than the investment in our transportation infrastructure," he said.

Development.

In the early 2000s, Denver introduced the idea of "areas of stability" and "areas of change." The result: A lot of people were pretty surprised when blocky new condominiums started to fill out single-family neighborhoods.

This new plan suggests some changes in how the city would manage and talk about development in various neighborhoods. It largely gets rid of the idea of "areas of stability," trading it for the idea that different neighborhoods will change in different ways.

New maps designate various "centers" and "corridors." For example, I-25 and Broadway with its Gates Rubber site could be a "regional center" for some of the most intense development. Colfax Avenue and transit-station areas would see smaller but significant change.

"No place is in stasis. Every place evolves in some way, shape or form," said planning director Brad Buchanan. "It is not a black-and-white conversation, as much as folks would like it to be. Some areas are going to have more evolution than other areas."

That could mean change even for existing residential areas. For example, the city could "modernize" its rules about group living and allow more accessory dwelling units.

It also could try to encourage more duplexes and four-unit buildings on corner lots and in denser areas. Meanwhile, the city could get rid of some requirements for minimum lot sizes if they "restrict the development of multifamily housing where it is otherwise appropriate." And former church sites near residential areas could be tweaked to allow higher-density housing and taller buildings with limited parking.

But the plan does call for some potential limits and requirements for development. That includes the potential creation of committees and rules for "design review" to ensure that new architecture fits into certain areas.

Meanwhile, in denser areas, the city could require space for shops and other non-residential uses on the ground floors of buildings -- which could be a response to fears that apartment-only buildings are crowding out the charm of shopping areas like South Pearl Street.

The city also could consider increasing requirements for accessible open space in large developments and for tree planting. And it could even implement more rules about what you can build near transit stations -- apparently a response to the proliferation of storage units and other unwanted buildings.

Parks.

The city's new plan declares that its parks system is "not keeping up with growth." On average, the city has 9 accessible acres per thousand residents, "well below the national average of 13."

The city's new mindset, according to the plan, is to treat parks as "vital urban infrastructure," which can support the natural environment, control flooding and provide for recreation.

"Our focus has been on the healthier city, creating a healthier city," said parks director Happy Haynes.

The goals include:

- Plant more trees, especially in hot urban areas, and potentially incorporate new technology to support trees. The goal is to have at least 18 percent canopy coverage. Neighborhoods in central, western and northeastern Denver tend to fall short.

- Create more natural and low-water landscapes, getting rid of bluegrass lawns in some areas.

- Consider creating new fees on development that will fund parks, and a new nonprofit foundation to support parks.

- Restore vacant and degraded urban land. The overall goal is to bring every neighborhood within a 10-minute walk of a park. Part of the focus will be on "high need" areas where residents are less likely to own a car, populations are higher, income is lower and people's health is poorer.

- Adjust rec center strategies to better engage surrounding communities. A survey found high demand for arts and culture offerings, followed by pools and fitness facilities.

- Conduct more surveys to understand what people want, and create better signs and information to show them what's available.

- Work with Denver Public Schools to allow more public access to school recreation facilities.

Walking and biking.

The new plans identify nearly $2 billion of potential spending to complete the sidewalk network, build new greenway trails, create safer railroad crossings and more.

Some of the highest priority projects would be on the "high injury" streets -- which account for just 5 percent of the grid but half of all traffic deaths. Next up would be areas near transit, and then destinations such as schools, parks and grocery stores.

Around the city, Denver would try to create raised crosswalks and "refuge" islands in roads for pedestrians, among other changes.

The plan lays out dozens of specific projects, such as a new pedestrian overpass above the railroad near I-25 and Broadway, possibly connecting the South Platte River to Broadway.

Interestingly, it also calls for new trail design standards -- including one that would create three lanes on the Cherry Creek Trail on its busy section south of Colfax, where pedestrians and cyclists are currently crammed for space.

What's next?

These plans are still drafts. Each one included input from various public meetings and surveys.

Now, they're open for public comment for the next 90 days, through Oct. 31. After that, the land-use and parks plan will go to Denver City Council for approval, while the transit plan only needs approval from the mayor's administration.

There's no guarantee, again, that any of this happens. But the plans do set the expectation for the decades to come, and they signal which direction the administration's moving.