Decades later, the memory of fences and bulldozers still haunts Gregorio Alcaro.

Alcaro was 11 years old when an urban renewal project forced his grandmother and hundreds of her neighbors out of central Denver. He remembers as well the tears, illnesses and other signs of stress among the adults on whom he counted. His mother "spent the best years of her life trying to save this place," he said.

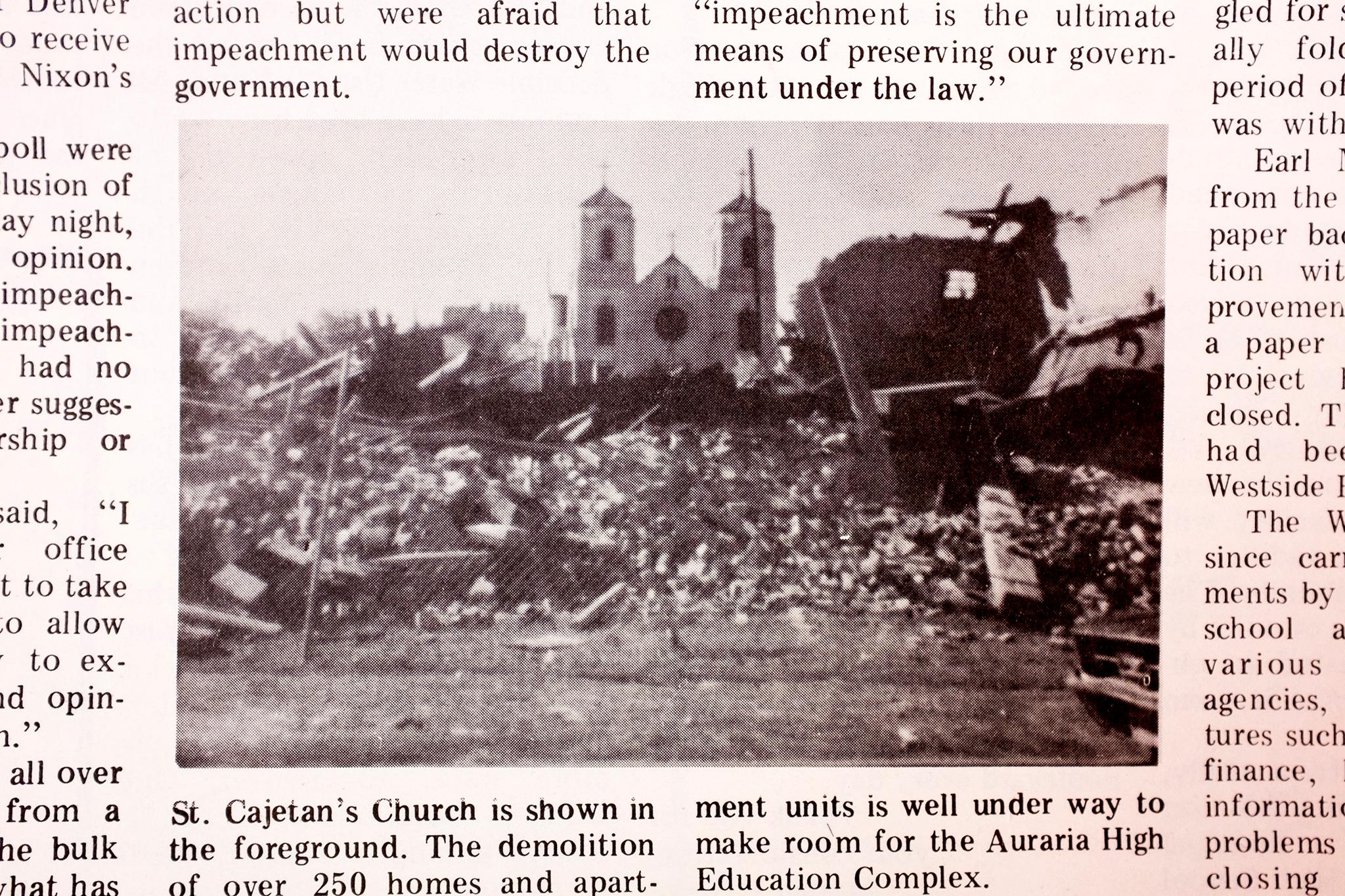

Most of the neighborhood's brick or wood homes and businesses were razed beginning in 1969 to be replaced by the modern concrete-and-glass buildings that comprise Auraria Campus, home to the Community College of Denver, Metropolitan State University of Denver and University of Colorado Denver. A 3-acre block that included the house where Alcaro's family lived and ran a restaurant and cultural center was fenced off during the removals so that its Victorian buildings could be preserved and used as faculty and department offices for the campus that opened in 1976. In all, 250 businesses and 330 households were displaced.

"They could say they were paid for their homes. But you can never replace a community," said Alcaro, who often apologizes for being "emotional" when he talks of what happened to Auraria, the neighborhood that gave the campus its name.

Alcaro's past will resonate with many in changing neighborhoods who fear for their futures. He embodies the human costs of development, but also offers a lesson in resiliency. And he is a living link to a history that could shape the conversation about where Denver is headed.

Where to begin a discussion?

Consider what it means to create a home out of a spot on the map, and how outsiders can miss or misinterpret the investment residents have made. Sometimes, prejudice informs the misinterpretation.

Auraria was founded on the banks of Cherry Creek in 1858 as an independent town. It merged with the only slightly younger Denver in 1860. Both Auraria and Denver were settlements of immigrants from Europe, New Mexico, Mexico and elsewhere.

By the 1960s Auraria was largely Hispanic and working class. Politicians and planners looking for a site for a new campus to revitalize downtown and create new higher education opportunities saw a chance to remake a part of town long looked on with suspicion by the larger white community. As scholars Brian Page and Eric Ross wrote in the journal Urban Geography, in Denver "the term blight as applied to Auraria signified a minority-filled urban space that was poor and deteriorating, yet capable of overrunning the rest of the city if left unchecked."

Auraria residents resisted that depiction. They saw themselves as a "supportive cultural community," Alcaro said.

"We were not lazy, stupid, dirty Mexicans, criminals."

Alcaro's great-grandparents Trinidad and Belen Gonzalez left Chihuahua with their family during the Mexican Revolution, coming first to Texas and New Mexico, later to southern Colorado and then Auraria. In 1933 they bought 1020 Ninth. Built in 1872, it was the oldest house on the block. Trinidad and Belen's son Ramon and Ramon's wife Carolina opened Casa Mayan on the ground floor in 1947. In later years it was run by other members of the family, including Joe Arnold Gonzales and Erminia Gonzales.

Casa Mayan became a multicultural hub run by a creative and welcoming family. Diners included Tex Ritter, William Shirer, Andres Segovia, Marian Anderson, Paul Robeson -- and local intellectuals, artists and politicians who turned the restaurant into a kind of salon.

Alcaro's mother, Marta Rosa Gonzalez, helped run the restaurant. Her watercolors adorn a framed menu that is among the family mementos on the walls today. Her brother composed music and read so widely the neighbors called him Professor. Alcaro, an architect, is professorial himself in round, wire-rimmed glasses, a graying ponytail trailing from his Greek fisherman's cap. He said his uncle left school at 13 to work, so would have been labeled uneducated by the statisticians who compiled the reports that led to Auraria's designation as blighted and in need of renewal.

Aurarians resisted removal.

Arrayed against them were the Denver Urban Renewal Authority, City Council members, Mayor Bill McNichols (who said during the debate over urban renewal that "Auraria is a deteriorating area. That's not an indictment against the people in the area; it's a plain fact"), politicians holding state office and business leaders. Denver's Catholic archbishop supported the campus plan even though the largely Latinx St. Cajetan's in Auraria had been a hub for opposition organizers. The Spanish Colonial style St. Cajetan's building, erected in 1925 and once the center of the oldest parish serving Spanish-speaking Catholics, is now a campus event center.

Luis Torres, who came to Metro State to develop a Chicano studies department in 1995 and went on to hold administrative posts, has researched the founding days of the campus. He notes the closeness of the vote in which Denverites approved a bond issue for the city's share of the project. After a campaign in which Aurarians wrote letters, held public meetings and lobbied officials, the vote was 53 percent in favor of and 47 percent opposed to the proposal to raise $6 million. The $24 million project also drew on state and federal funds.

Torres said the pro-campus forces assumed, "'These are Mexicans, these are Latinos. They can't really fight.'

"But they did. They put up a strong fight. Because they didn't want to lose their homes. Who does?"

Alcaro has symbolically reclaimed his family home.

The two-story green house at 1020 Ninth Street has a front porch that invites you to sit for a chat. Other buildings along a tree-lined, grassy Auraria Campus mall known as Ninth Street Historic Park are college offices. No. 1020 is a small museum, albeit open only upon request.

Professors hold the keys. But Alcaro can take students and other visitors on tours, pointing out artifacts such as a photo of the final meal served in the Casa Mayan restaurant that the family ran on the ground floor of their home. Among the guests pictured is renowned Denver architect Temple Buell.

It's difficult to imagine putting a value on all that the Gonzalez family made of their home. When it came time for relocation, they were offered a spot in a strip mall for Casa Mayan.

"It was humiliating," said Alcaro, who by then was living with his immediate family in North Denver.

The family closed Casa Mayan. The widowed Carolina Gonzalez moved from upstairs at 1020 Ninth further west, to a small duplex in Athmar Park.

"It was not a community," Alcaro said of his grandmother's new street. "It was a place people lived and rented and left."

Torres, who retired from Metro this past June, was once a CU Boulder undergrad involved in the then-nascent Chicano civil rights movement. The young Torres would travel to Denver to meet with like-minded young people and dine at Casa Mayan. The debate over Auraria helped energize El Movimiento.

Torres questions whether displaced Aurarians were fairly compensated.

Similar concerns are being raised today by residents of Globeville and Elyria-Swansea, Denver neighborhoods threatened by gentrification and a highway construction project that, like Auraria was, are largely Latinx and poor. Torres said there's evidence Aurarians were not paid enough to allow them to stay in Denver, another current issue as home prices soar in the city.

Torres said he found in minutes from meetings about relocating Aurarians that oral promises were made that were never written into agreements.

"I remember going through (documents) and thinking, 'This is just really underhanded,'" Torres said. "If somebody wants to lose faith in the government, read through these minutes."

Fast forward to community meetings in Globeville and Elyria-Swansea, at which residents can be heard expressing skepticism government officials will make good on promises.

One pledge that resonated even with Aurarians who did not want to leave their neighborhood was an assurance that their children could be educated on the new campus. It was two decades before that was realized in the form of the Displaced Aurarian Scholarship for undergraduate and graduate students who were residents of the Auraria neighborhood between between 1955 and 1973. Children and grandchildren of Aurarians also are eligible for the scholarships.

"It really took too long for that to come to pass," Torres said. When it did, "it was because the community representatives and the community members kept insisting."

Rebecca White, a communications specialist for the Colorado Department of Transportation, has seen such persistence among community members in Globeville and Elyria-Swansea whose lives have been disrupted by a project to renovate and widen Interstate 70. Scores of homes and businesses were demolished in the neighborhoods in preparation for the construction, which recently began and will continue for years.

Protests and court cases did not stop the highway project.

CDOT says it is improving I-70 to increase safety and reduce traffic jams on a key east-west route. Residents forced to sacrifice for the greater good wrested some benefits for themselves and their children.

CDOT, for example, provided the first $2 million to help develop a land trust that residents researched and pushed for in hopes of ensuring that housing remains affordable in the neighborhoods. CDOT also worked with partners that included Gary Community Investments -- which combines philanthropy and investment to help low-income communities -- to start a job training program for local residents. And CDOT helped build a new wing for Swansea Elementary and provided the school with a new doors, windows and a heating, ventilation and air conditioning system.

"This is a neighborhood that has a very strong voice," White said.

Tracey Stewart, who focuses on family economic security as investment director for Gary Community Investments, said policy makers are more likely to listen to such voices now because of progress made by activists who have come before.

Stewart is an African-American with family roots in Five Points, a historically black neighborhood that has been transformed by gentrification. Stewart worries about stubborn economic and racial inequities in Denver and said much remains to be done. But she added that progress has been made.

"People need to understand that there is a continuation," she said.

Candi CdeBaca, an activist and youth development worker who lives in the Elyria-Swansea house that her grandparents once owned, worries that many people feel disengaged after decades of struggle for gains that can seem hard to measure.

"It's always been this really abusive relationship with government," she said.

Some gains can be counted.

Since the first scholarships for displaced Aurarians were awarded in the mid-1990s, CU Denver has awarded more than $2.6 million in funding to 150 students, 63 of whom obtained degrees. This fall 20 students started CU Denver on the scholarships, in line with the average of 15-25 a semester. The Community College of Denver was not able to provide as much information, but did say 119 students had been awarded such scholarships since 2006, with the average amount of $1,824, and that 26 of those students had graduated. CCD currently has 18 Displaced Aurarian recipients on campus.

Torres's Metro State has funded a total of nearly $2 million in scholarships under the program since 1994, benefiting 272 students who have taken classes. Of those, 68 obtained degrees. According to school records, 36 students are currently receiving scholarships totaling more than $250,000 for fiscal school year 2018-19. Historically Metro has averaged around 20 students on the scholarship each year.

Torres said reaching out to displaced Aurarians is part of a broader effort to serve minorities. CCD has and Metro is approaching Hispanic-Serving Institution status, a federal designation recognizing colleges and universities that have a student population that is at least 25 percent Hispanic.

"We want to serve the population in the area," Torres said. "We're educators. That's what educators do."

"We understand the pain and the difficulties that the people went through when they were displaced," he added. But "ultimately it had the effect of bringing higher education to the community."

Yessica Holguin grew up in Swansea and attended CU Denver.

Holguin earned a bachelor's in business administration with a focus on information systems and a minor in Latin American literature in 2003. Her master's in management and organization with an emphasis on human resources came in 2004.

Now she's working to improve economic opportunities among minorities as a fellow for Community Wealth Building, a Denver network of people and organizations dedicated to equitable economic growth.

Holguin has seen Swansea businesses where she and her family once shopped closed to make way for the CDOT project or on the brink of bankruptcy because of construction-caused disruptions. Speculators are gambling the area will be more attractive because of the highway changes and plans to develop Globeville's National Western Complex. Holguin, who no longer lives in Swansea, has heard of her old neighbors being approached with offers to buy their homes.

Looking back on Auraria, Holguin said "people were active in ensuring there was a scholarship. Our role now is determining what is the equivalent of a scholarship for the people of Globeville-Elyria-Swansea."

That could include an agreement by National Western to do business with local entrepreneurs. How that might look is being hammered out in forums such as a citizens advisory committee, which was formed in 2013 and meets monthly to bring together residents and policy makers including representatives from nonprofits, the city and Colorado State University, which will be part of the National Western campus.

Empowerment and the local economy are on the agenda. Last year, Mayor Michael Hancock announced an investment fund he envisions people in Globeville and Elyria-Swansea deciding how to use. Earlier this year, the National Western Center Authority and City Council approved investing $550,000 for more job placement, training, and support services offered by WORKNOW. WORKNOW supports people in the Denver area whose neighborhoods are affected by community construction projects.

"I think it can be a win-win situation if the communities are taken seriously," Holguin said. The key is ensuring "what they're giving is not just charity, but is actually changing the economic environment of the community."

Meanwhile Holguin is working on linking CU Denver events staff to small caterers, including some in northwest Denver. The tenacity of the entrepreneurs with whom she works is inspiring, she said. Their "determination to work hard despite the odds gives me the determination to work even harder to support them."

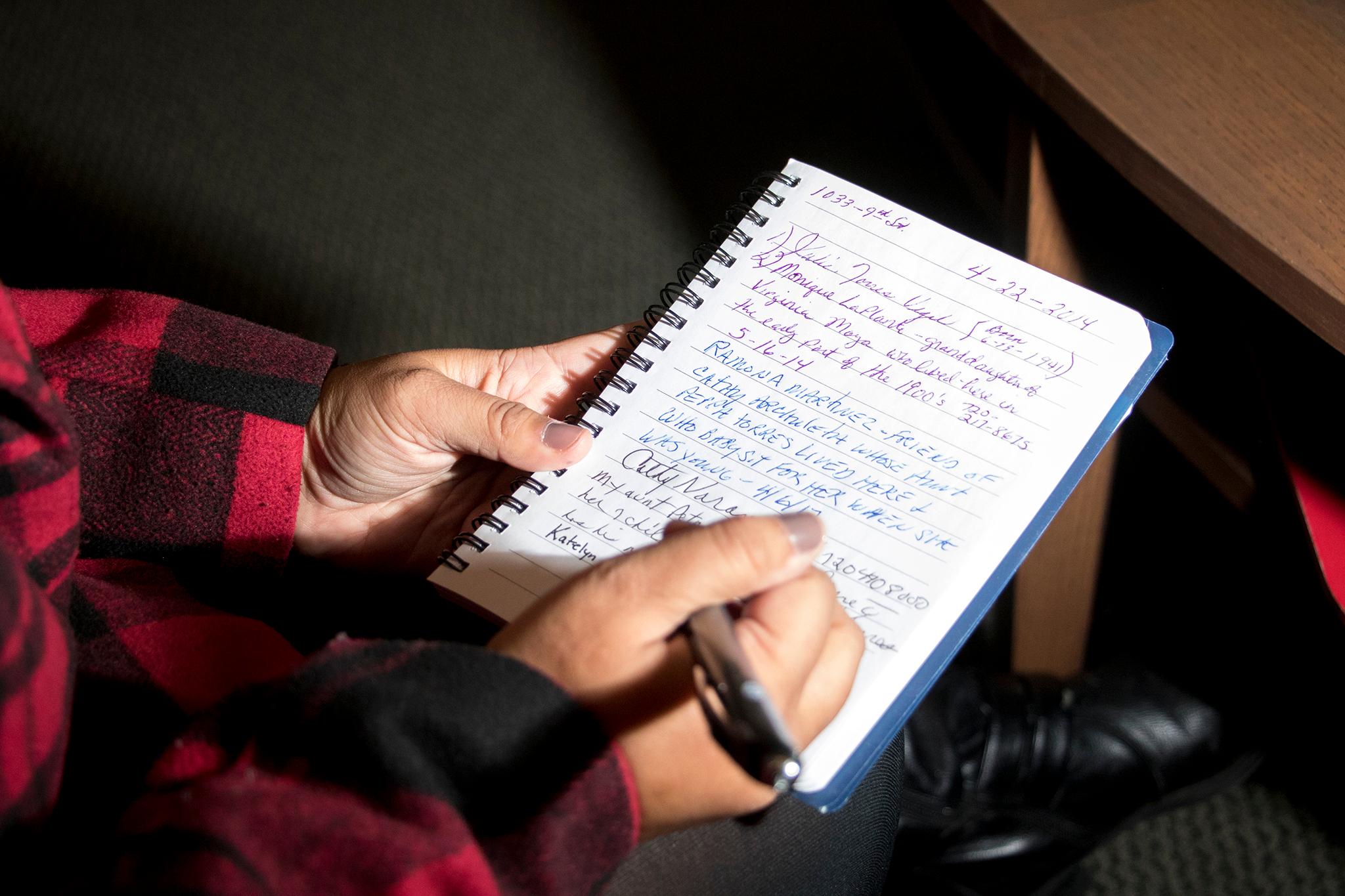

Another CU Denver alum, Katelyn Puga, recently visited her alma mater's campus. Puga stopped by a wooden Victorian painted light brown that houses the offices of Metro's center for honors students. When she explained who she was, Puga was asked to sign a guest book. She beamed when she found her grandmother's signature on the pages. Her grandmother, Julie Torres, who has no relation to the Metro academic, grew up in the house.

"I love taking my grandmother to campus. She will stand in the middle of Ninth Street and just stare," Puga said. "She's just in awe that it's still there and that it's always going to be there."

"To us, it's (like) a museum. To her, it's her life."

Julie Torres used to tell Puga stories like the one about a boarder she and her siblings feared and nicknamed La Llorona. Puga also grew up hearing about her great-grandfather Phillip Torres. He was a businessman who founded a credit union for St. Cajetan's. He helped campaign for the displaced scholarship Puga used to earn a bachelor's in geography in 2015 and a master's in urban planning in 2017 from CU Denver. She's now a planner for the city of Thornton.

Her grandmother attended both of her graduation ceremonies.

"She always says that her dad would be so proud of me, that I took the scholarship."

Puga's younger twin brothers have taken classes on the Auraria campus and at least two cousins also took advantage of the scholarships.

"I come from a big Hispanic family -- there could be more," she said, and laughed.

In a family photo, Phillip and Petra Torres pose with other members of a wedding party, he in a dark suit, she in a hat with a wide, elegant brim.

"I've been told I look exactly like her," Puga said. It's true.

Petra Torres was just 59 when she died.

"My grandmother swears she died of heartbreak because she was torn from her community," Puga said. "It's hard because our family had to move. But it propelled us forward."

"Generations later, we're seeing the positive."

During her student years, Puga would sometimes find herself pausing as she walked back to her car after classes and thinking, "This place kind of grew me, grew my family. And now it's helping me grow."

Puga is fascinated by history and communities. As an undergrad she researched what happened to Auraria and as a graduate student looked at other communities coping with change. She became an urban planner, with an interest in how the past shapes today's choices.

As an architect, Alcaro's practice has included helping communities participate in the design and development in their neighborhoods. He believes history can inspire people to solve problems.

Alcaro, standing one afternoon on the porch of his old family home, greeted a campus staff member who worked next door and pointed to a gnarled, hollow tree that still was managing to sprout leaves.

"I have a photograph from 1930 with this tree," Alcaro told his neighbor. "And it was old then."

Adds names of other family members who ran Casa Mayan.