After running a stop sign at Fifth and Lincoln in the winter of 2017, a driver guaranteed that three children would grow up without their father, Derrick Keith Brown. The 43-year-old was riding his motorcycle to work when the driver struck him, killing him instantly.

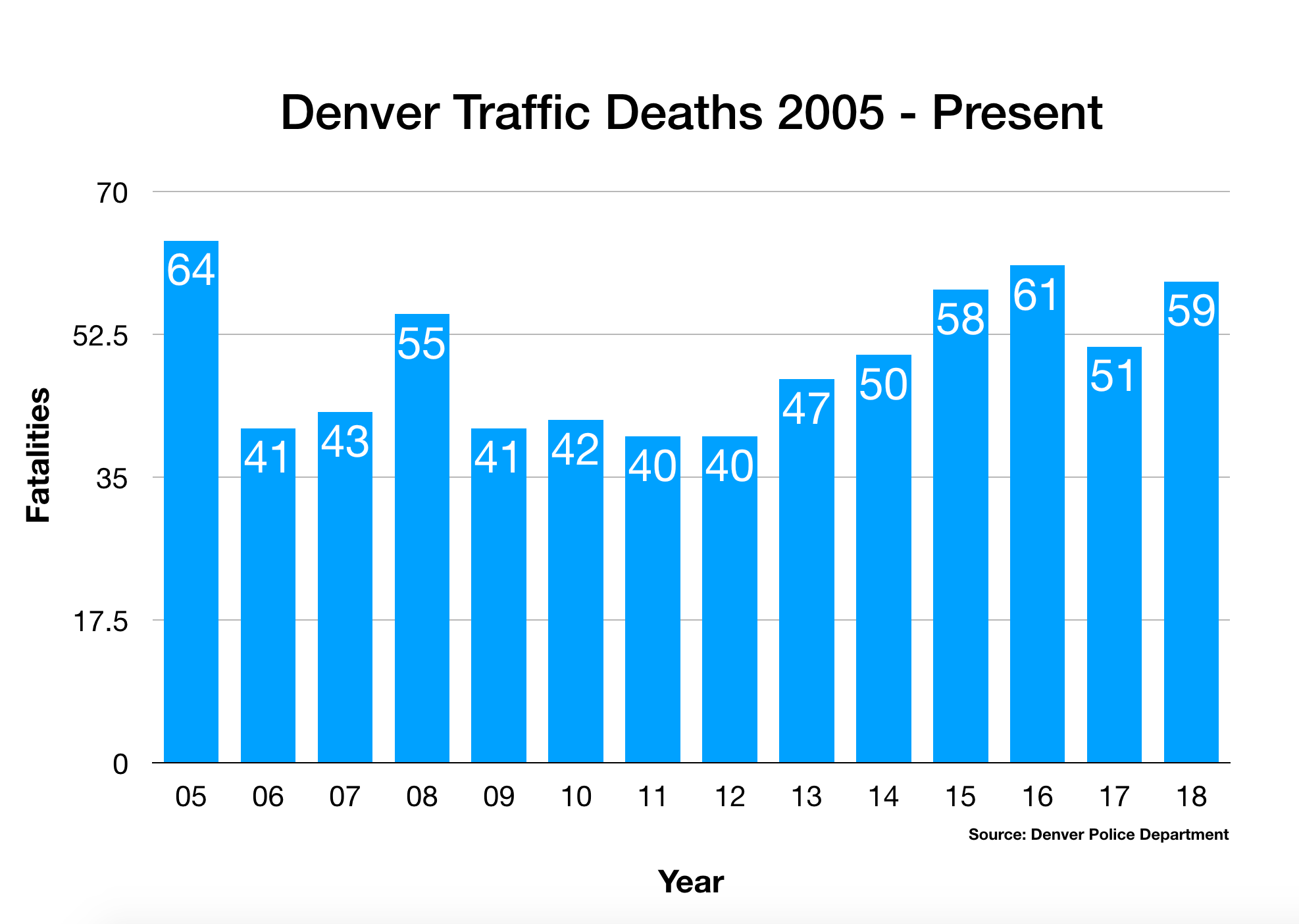

Brown was one of 51 victims killed in transit last year. With a month left to go in 2018, Denver has surpassed that human toll. Fifty-nine people have died this year trying to move around the city, according to the Denver Police Department.

"People honestly do not seem to care. They drive so carelessly, they don't pay attention to the speed limits, street signs, lines, the cars around them," said Rebecca Ross, a lifelong friend of Brown's and mother to two of his children. "And if you're on a bicycle, motorcycle or walking, you're at such a disadvantage. I watch people texting, taking selfies, putting on makeup, lighting cigarettes, all while driving. As if driving is getting in the way of the other things they're trying to do."

Ross happens to be the sister of Crissy Fanganello, who oversaw the beginnings of Mayor Michael Hancock's initiative to end traffic deaths by 2030. It's been 21 months since Hancock committed to the onerous task under the banner of "Vision Zero." The nationwide movement views traffic fatalities as preventable and seeks to end them with a systemic approach -- engineering, enforcement and education -- rather than focusing on individual behavior.

The administration has ideas for how to curb deaths. In many cases, they're still just ideas.

The death toll indicates a transportation system that has yet to truly change, despite an apparent change in mindset.

"It's more than just the whole numbers at the end of the year," said Eulois Cleckley, executive director of Denver Public Works. "It's more about the causes leading into those numbers and understanding ways in which we can be more aggressive."

Cleckley, whose department plays the largest role in ending traffic violence, hired a Vision Zero coordinator last month and has established a policy office to change how the city designs and maintains streets.

Hancock's Vision Zero Action Plan calls for calming traffic speeds -- the most fatal factor -- with lower speed limits and physical changes to streets that slow drivers down and prioritize pedestrians. Examples include traffic circles on West 35th Avenue and an intersection overhaul at Colfax, Park and Franklin.

The city needs to aggressively install more of those inexpensive, rapid treatments made mostly of paint and plastic, says Jill Locantore, a member of the Vision Zero Coalition, a group of safe streets advocates.

"I think Denver needs to stop being much too timid," Locantore said. "It's a mindset. They want to engineer something to death, but when people are dying, there's an urgency to get stuff on the ground."

DPW and the Colorado Department of Transportation are supposed to transform one dangerous corridor, such as Federal Boulevard, by the end of 2019, according to the plan. DPW is processing data collected last month at 37 locations throughout Denver, DPW spokeswoman Nancy Kuhn said, and will use it to prioritize streets for changes.

The document calls for policy changes, too, plus a scroll of other measures. Some are wonky, like changing street design guidelines. Others are straightforward -- building 14 miles of sidewalks by the end of 2019. Closing in on two years since Hancock's commitment, the city has only built 2.2 miles, according to DPW spokeswoman Nancy Kuhn.

The gears have started turning, slowly, on a policy that ensures safe walkways in construction zones, which pose a major problem for pedestrians and wheelchair users, the system's most vulnerable users.

Meanwhile, people keep dying.

Denver darted past last year's tally in October. A deadly Thanksgiving holiday weekend, which included the deaths of one person walking and one person riding a bike, nudged the city further past the mark.

DPW is in the midst of major restructuring and has experienced turnover since Cleckley took the helm. The department deserves some slack, Locantore said, but needs to deliver in 2019. "They have come up with a great plan but failed to implement it in a timely manner," she said.

The supposed paradigm shift has yet to sink in street-level, Ross said.

"I have children so even before (Brown's death), I would pay attention to how horribly people drive through school zones," she said. "It's amazing that even children cannot get people to slow down and pay more attention. I tried to get more signs up in their school zone; I tried to change where the crosswalk was for their middle/high school campus. But it feels like an impossible task. If it fits into whatever the norm is, and how engineers think it's supposed to work, it doesn't seem possible to get things changed."

This article was updated to correct the name of Rebecca Ross.