A city councilwoman and a nonprofit's board chair walked up to a coffee bar.

It's tough to say what the eventual outcome might be of the ensuing conversation about affordable housing and bond measures between north Denver Councilwoman Candi CdeBaca and John Ikard, chairman of the board of directors of the National Western Center Authority, which guides the massive agricultural, research and entertainment campus that will replace the stock show complex in Elyria Swansea. Scott Turner, executive director of the White House Opportunity and Revitalization Council, said such encounters elsewhere have led to creative development solutions.

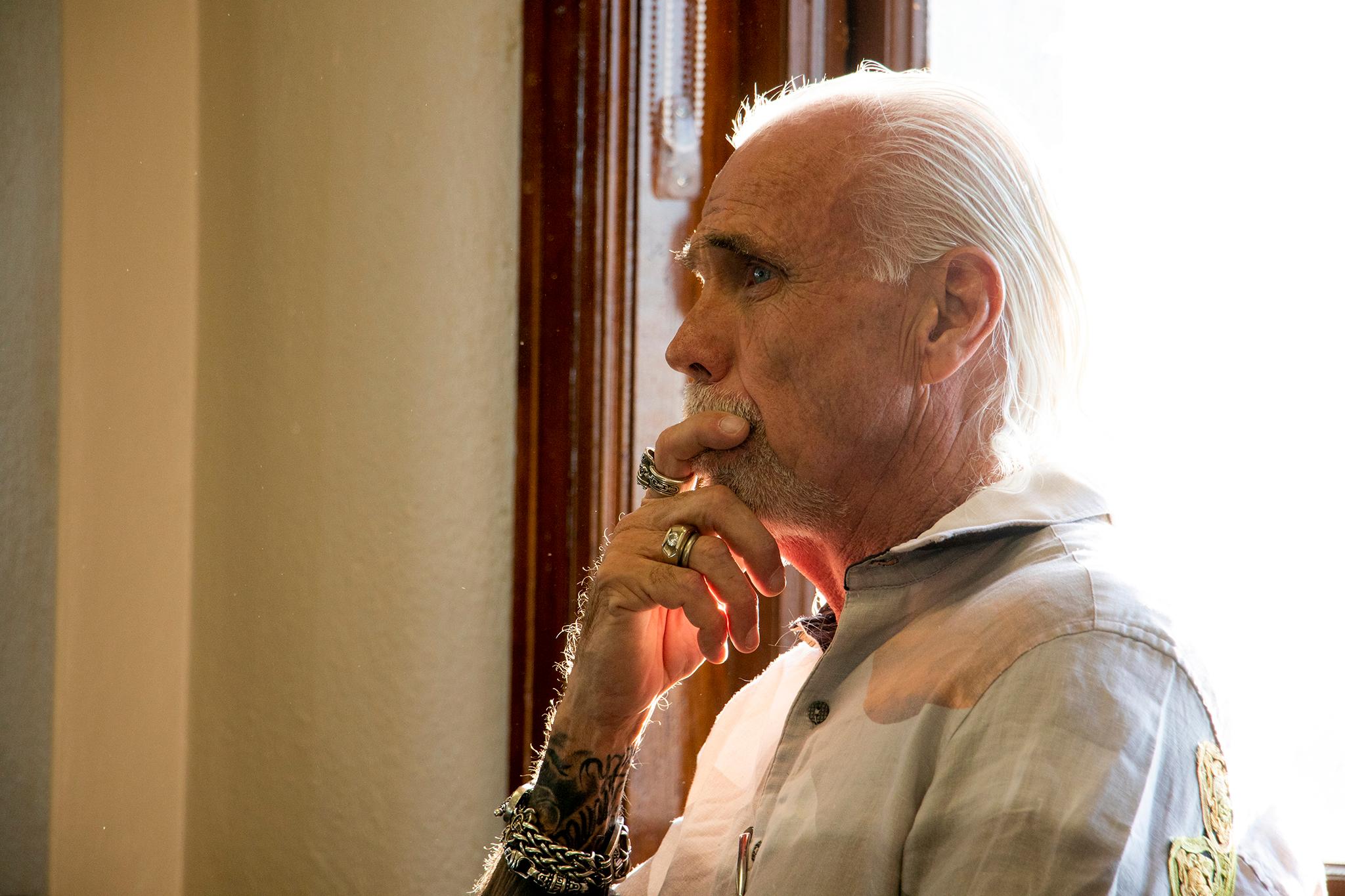

Turner came to Denver Thursday to bring Cdebaca, Ikard and a dozen other government, business and community leaders together for a roundtable on "opportunity zones." The zone program, created as part of the Trump administration's tax cut legislation that Congress enacted in 2017, allows private investors to get tax benefits on profits they invest to develop designated low-income communities. The National Western Center sits in such a zone, which includes Elyria-Swansea and spreads east to Stapleton and north to Adams County. The roundtable was held at the offices of the National Western Center.

Opportunity zones have been met with questions about whether long-neglected communities such as those neighboring the National Western campus will benefit and be treated as partners.

"I object to some of the ways that the community is being talked about. It feels a bit like manifest destiny -- 'We're going to swoop in and save the poor people that have been here,'" said Lisa Calderón, CdeBaca's chief of staff, who also took part in the roundtable.

"Opportunity zones have been used to get rid of and displace communities of color," Calderón said during the roundtable.

Ikard said during the discussion that Globeville and neighboring Elyria-Swansea "have not shared in the economic development and they quite frankly have been disrespected."

Turner, a former member of the Texas House of Representatives, acknowledged the weight of the past.

"I know what has happened historically. People have been displaced," he said.

"This new tool," Turner said of opportunity zones, "is bringing not just investment. It's bringing people who care about communities together."

In his role with the White House Opportunity and Revitalization Council, Turner said he has toured dozens of opportunity zone projects around the country. New ideas came out of bringing people together to talk, Turner said.

"We've got to drive that conversation," Turner said. "That's my job."

He said the zones give local authorities flexibility to ease construction permit fees and temporarily freeze property taxes, saving developers money that can be passed on to homeowners and renters.

CdeBaca said, "I don't think it's the permitting or the taxes that are preventing the development. I think it's the cost of construction and the price of land."

During the roundtable, Bernard Hurley, a developer who is active in the area, said he got his start because he was given an opportunity even though he had been in prison. He asked Turner whether the program included measures to encourage contractors to hire people who have been in prison or experienced homelessness.

"If you just help them, it will change lives in a significant way," Hurley said. "It changed my life."

Turner said the federal government was not making such requirements, but that local governments could. Turner believes private companies with social consciences would take steps to help neighborhoods. Hurley was skeptical. Only a minority of businesses could be expected to do so without government prodding, he said.

"This is a locally led and privately led deal," Turner said. "The federal government is just a facilitator."

CdeBaca said federal funding for housing was decreasing and questioned how much progress could come without government investment. Evelyn Lim, the Denver-based regional director of the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development, said the program did not mean new funding for housing, but said HUD would use grants from existing funds and other incentives to prioritize development in the zones.

After the roundtable in a room at with windows offering a wavy antique-glass view of the stock yards, Ikard and CdeBaca ended up at the back at a table laden with coffee and paper cups. The board chairman handed the councilwoman his card. The two fell into a discussion about a 60-acre tract known as the Triangle between the stock show arena and the Denver Coliseum. The National Western Center plans call for an as-yet determined contractor to build and renovate stock show structures and get land for development that could include housing.

In 2015 Denver voters approved borrowing up to $476 million to be repaid with taxes on car rentals and lodging for the National Western Center. CdeBaca suggested to Ikard that the voters be approached again to ensure affordable housing comes to the area, noting that he and other city leaders had shown they could persuade voters to accept big projects.

"You think the Triangle proposal could go back to voters?" Ikard said.

"I think the city needs to do a bond for housing and that could be part of it," CdeBaca said.

Patrick O'Keefe, program director for Jacobs, the company in charge of program management for the National Western project, said later he expected housing to be built on the Triangle.

"If they build housing, they have to have affordable," O'Keefe added.

After the round table Turner and others in the group took a tour of the site and neighboring areas on one of the buses used to shuttle stock show visitors. Liz Adams, deputy to the chief executive officer of the tried to get passengers to envision a vibrant future. She also pointed out the way a tangle of highways and railroad tracks can make it hard for children to get to school, discussed the lack of grocery stores and plethora of fast food restaurants, and mentioned the legacy of pollution and poison left by industry.

It was new to Turner, though the former professional football player was once a Bronco. Turner, who wore a blue sport coat and an orange tie to the roundtable, said he hadn't had opportunity to see much beyond the stadium and practice fields during his playing days.