Nearly four years after Mayor Michael Hancock declared traffic deaths unacceptable and set a goal to wipe them out by 2030, Denver is coming off of its deadliest year since 2000.

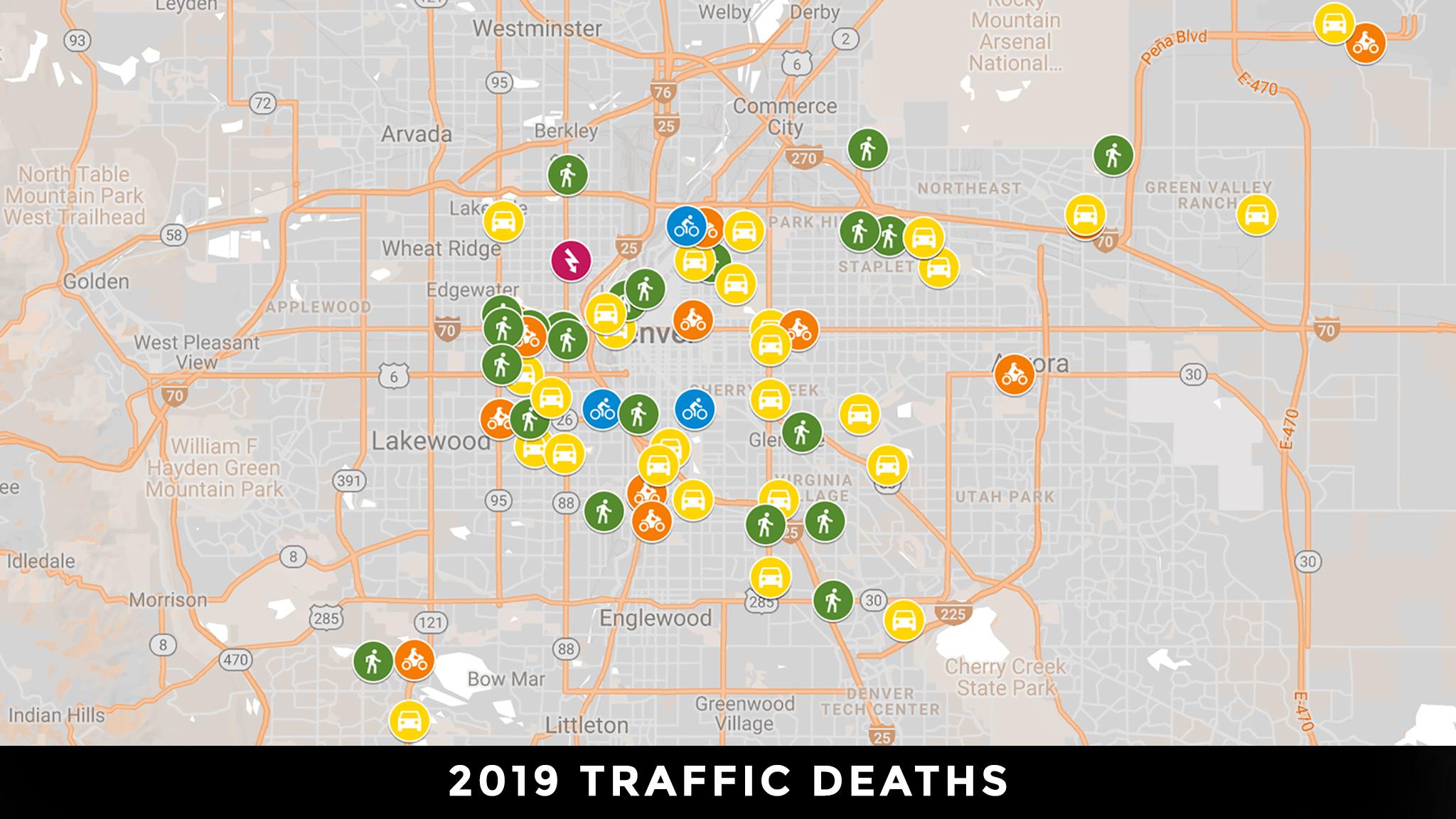

Seventy-one people died walking, biking, electric scootering, driving and motorcycling around the city in 2019, according to the Denver Police Department. The last time that many people died while moving around Denver, America was listening to Destiny's Child -- not a solo Beyoncé -- and the war in Afghanistan hadn't yet begun.

More than 500 people were seriously injured.

In an interview, Director of Denver's Department of Transportation and Infrastructure (formerly Denver Public Works) Eulois Cleckley was quick to point out that some of the pedestrians killed were on train tracks, not streets controlled by the city. Four people walking were killed by trains, according to Denver Police Department data.

Cleckley also noted that motorcyclist deaths spiked and comprised an outsize share of traffic deaths for how many exist citywide.

"I don't know if it's behavioral versus environmental, but that's something that we're going to be taking a look at," Cleckley said.

Vision Zero is a philosophy that views traffic deaths as preventable. It charges politicians and transportation planners and engineers with addressing the problem systemically with safer street designs and policies that slow motorists down. Cleckley says individual behavior is equally to blame -- intoxicated driving, texting while driving.

"Street design is critical but human behavior is just as critical," he said.

Safe streets advocates don’t totally buy the personal responsibility argument in a city where 40 percent of streets have shoddy sidewalks or are missing them altogether. Jill Locantore, who has watchdogged what the city has and has not done for traffic violence for years as the head of WalkDenver, points to Oslo as possible model. The Norwegian capital had relatively deadly streets by European standards before committing to Vision Zero. It just finished 2019 with one person dying in traffic. The city is 20 square miles larger than Denver with a similar population.

“Is it really the case that people in Oslo are just so much more conscientious and safe in their individual behavior? Is that how Oslo got to zero?” Locantore said. “What is the lesson we should be learning from cities like Oslo and how can Denver apply those lessons here?”

Locantore believes retrofitting streets to prioritize people walking, biking and e-scootering goes a lot further than telling people to slow down. That means adding bikeways and bus lanes to make options other than driving more viable, painting crosswalks, and calming traffic with inexpensive but effective plastic posts and markings.

Those things happened in 2019 at a faster pace than any other year since Hancock adopted Vision Zero. The city:

- painted 60 “high-visibility” crosswalks downtown;

- built 24-hour bus lanes on 15th and 17th streets;

- added four crosswalks with flashing lights for pedestrians;

- installed bright yellow signs in the middle of streets to alert drivers of crosswalks;

- installed 14 bike corrals;

- implemented a policy to ensure construction detours for people walking;

- lowered the speed limits (slightly) on five stretches of road;

- converted about 30,000 street lights to LED.

And crews just built 15 safer intersections along East Colfax Avenue this week.

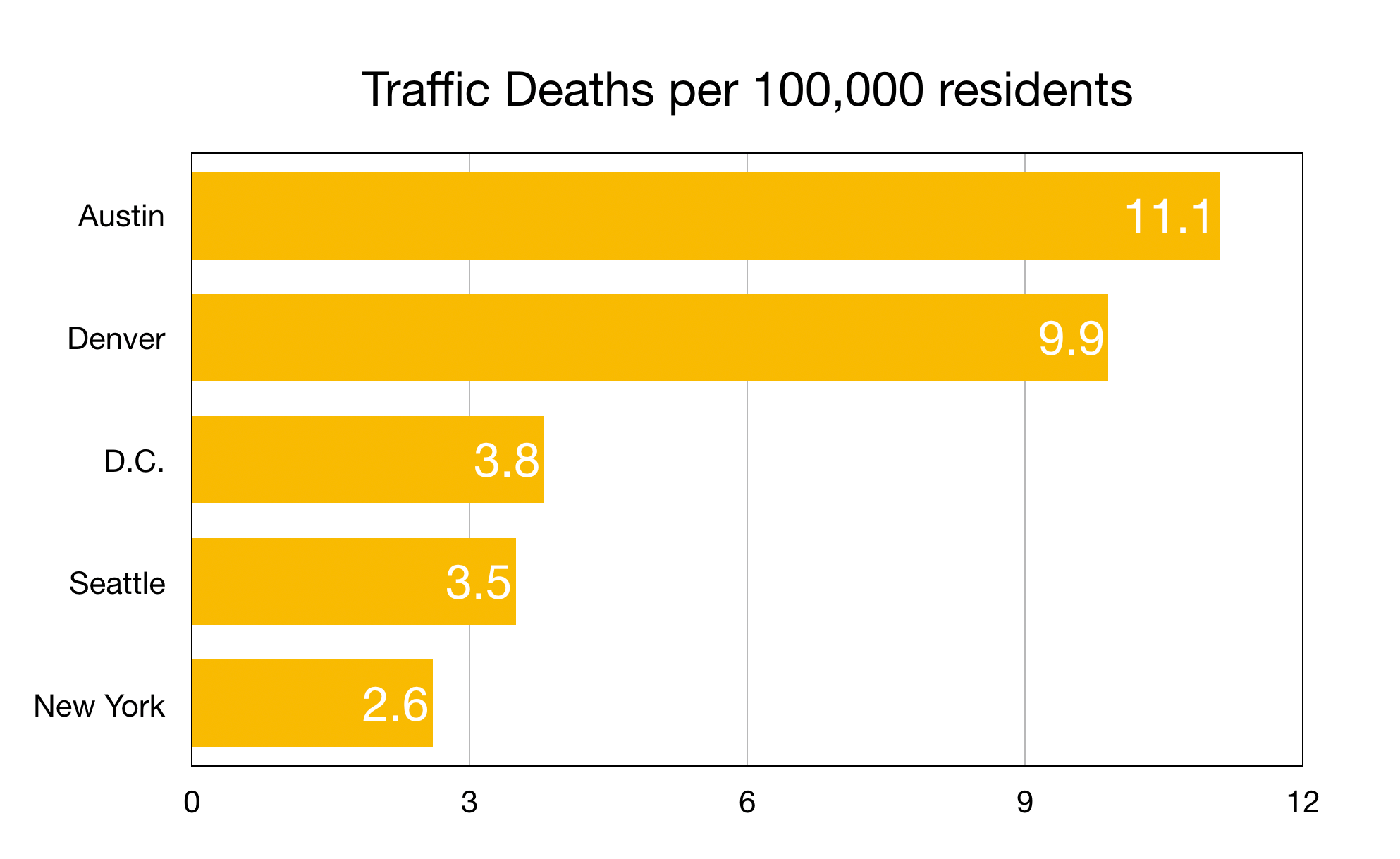

Cleckley said his team met every single day for four months to ensure those projects got done. Yet the deaths continue, and Denver lags behind some peer cities… and New York.

"My guess is it's just a result of the fact that we've got ever more cars on our streets and I think they've pushed the ability of our street system to function safely over the edge," said City Councilman Paul Kashmann, who has made safer streets one of his issues.

As a legislator, Kashmann says his effectiveness comes via funding but also policymaking. He secured money for DOTI to study the possibility of dropping the speed limits on Denver's residential streets from 25 to 20 miles per hour. Still, signs can only do so much, he said.

"Engineering is everything from what I've read," Kashmann said.

Locantore calls Kashmann a "champion" for safe streets, but her wishlist is much more aggressive. She wants to see turns-on-red banned citywide. She wants "beg buttons" -- those things people have to press if they dare cross a street -- thrown into the ocean in favor of intersections that assume people walking and wheeling are present. She wants the state legislature to expand automated traffic enforcement.

"Those are some of the sort of overnight things that will have some of the biggest impact on safety," Locantore said.

She also wants the transportation department to make good on its Vision Zero commitment to build 14 miles of sidewalks per year.

"Delivering our projects from the lens of safety is something that we're embedding in the culture of how we're pursuing our jobs on every everyday basis," Cleckley said.

Cultural change is inherently slow, and no one disagrees that Denver has a very long road to travel before reaching its goal of a truly safe transportation system.