On April Fools' Day in 2015, Brad Evans made a Facebook group to channel his displeasure.

He was driving near his home in Jefferson Park when he saw the thing that triggered him: rows of newly completed, boxy condos that nearly occupied the entire block. They were white and grey, each sitting atop a slatted blue foundation with lime green accents and pitched skylights on top. It looked like a container ship had parked on the grass.

"I was headed to my office, saw it for the first time, and muttered aloud to myself, 'that is (f******) ugly,' and went directly to work and launched this group," he wrote in a post to that group, recollecting.

His utterance that day inspired the name, Denver FUGLY. It now boasts over 9,000 members, who all mostly relish in a collective grousefest against new architecture (which they hate) that has slowly replaced Denver's older homes (which they mourn for).

Five years after the group's founding, Evans is channeling his obsession into art, painting the very objects he loathes.

Evans went to college for painting. He was a fine artist, and there was a time when he showed his work all over the place. But his last public display of personal work was in 2000. In the time since he's worked as a designer, fought against the I-70 expansion project, founded the Denver Cruisers, supported Jamie Giellis's mayoral campaign and, yes, railed against the city's architectural transformation. The top item on his LinkedIn page lists him as a "change agent," with specialties in "City Building 3.0 • Bear Poking • Civic Engagement • Pot Stirring • Agitation."

His dive back into the arts is a deeper exploration of Denver's shift to fugliness.

"This is another outgrowth of this ongoing conversation of how we see our physical world," he said. "We're in this place where the world doesn't look so pretty."

The first piece he shared with his group is acrylic painted on birch. It depicts a hulking, three-dimensional home of grey, yellow and brown. There's but one patch of green below it, a teeny bit of grass that survived the property scrape in Evans's imagination.

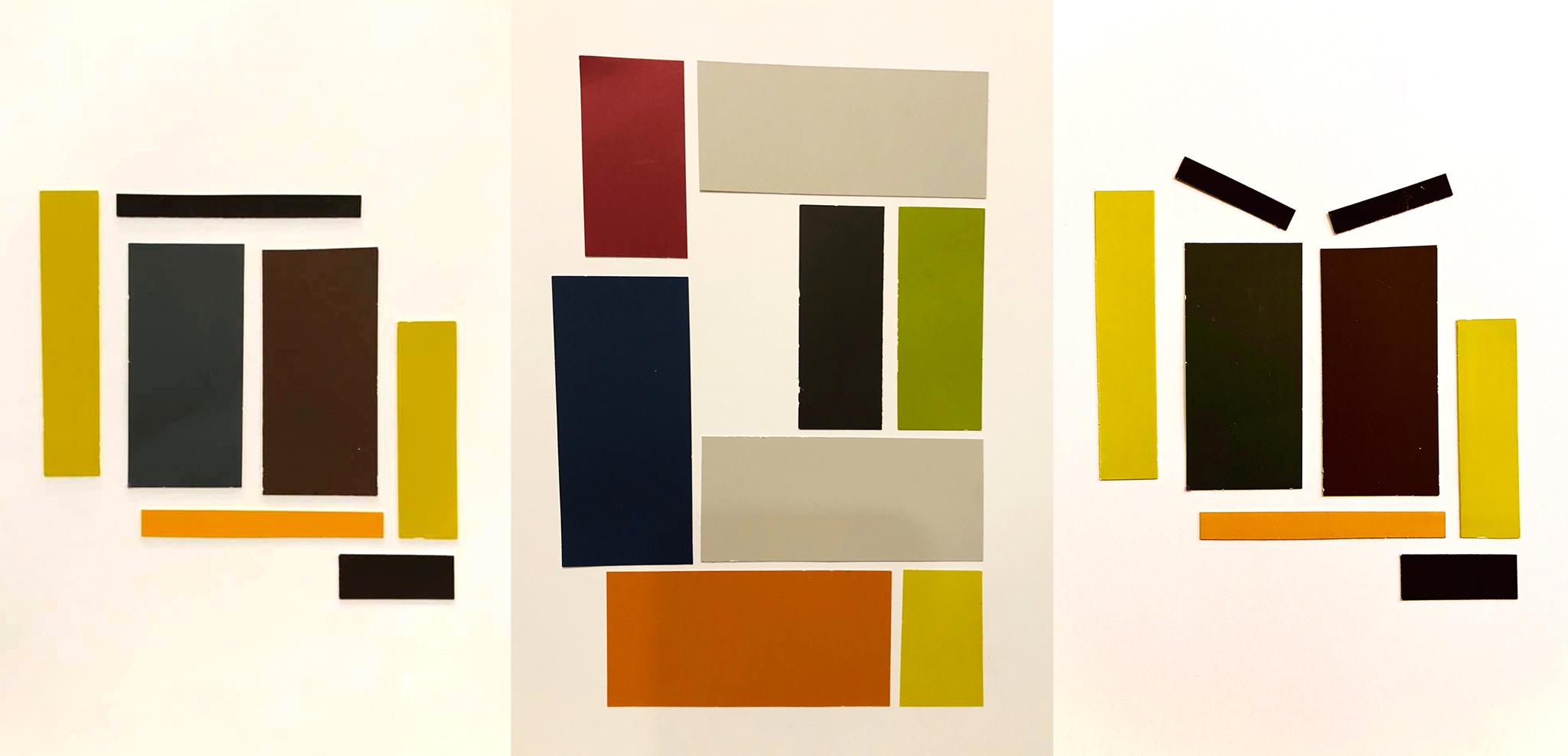

He also shared work made from paint chips, colored rectangles arranged to evoke the shape of a home. His audience responded with glee.

"Not fugly, Brad. Not fugly at all," one person commented.

"Love it. It will be on 38th soon," wrote another.

"Waaaay better than the buildings that inspired it!"

"You have a day job, right?"

Evans said part of his hatred for these housing designs is the context around them. It's not just a blocky house in a vacuum. It's a blocky house in a historic neighborhood on top of land where a pretty house once sat. It's offensive in its stark contrast.

Removing the fugly from that context and isolating it in a painting somehow turns it into a thing of beauty for him.

"It's transcended the ugly, and I'm just using this language of fugly as another way to look at it," he said.

But it doesn't mean he's starting to like how those homes look.

"I'm certainly not softening, I'm just trying to look at it in a different way. Bad design is bad design," he said. "Just because it's in our face all the time doesn't mean it's better."

Evans sees this exploration in line with artistic traditions championed by Charles Demuth and Charles Sheeler, who painted the hard lines of America's industrialized landscapes in the mid-20th century. As they made art depicting grain silos and catwalks and factories, a photographic exploration of the new American landscape was underway across the country and here in Denver. As part of the "new topographics" movement, Robert Adams documented how the Front Range had become suburbanized, creating a commentary through his images of repetition and sameness.

I asked Evans if he'd be upset if, someday, someone who lives in a fugly house bought his work and actually liked it, not getting the joke.

"It wouldn't crush me at all. It would add to the irony and the full circle of what is beautiful and what is ugly and the subjectivity of it," he said.

And, I asked: if you admit there's subjectivity to it, does that mean maybe this stuff isn't as objectively horrible as you think?

"I'll never submit to that," he said. "I think people know what's bad. Whether you choose to live with it is another thing."