Gov. Jared Polis's decision to gradually reopen Colorado raises questions about how Denver, home to the state's greatest concentration of COVID-19 cases and deaths, will shield itself against a potential surge as people reemerge into society.

Experts say more and better testing paired with a regional approach to reopening metro economies will be crucial. But politics also play a role.

The city's stay-at-home order expires April 30 -- Mayor Michael Hancock was considering an extension as recently as Monday -- but Colorado's stay-at-home order expires April 26, at which point localities can decide for themselves what to do. The statewide relaxation loosens rules on who has to stay at home, which businesses can operate and how close people can be, putting Denver's situation into sharper focus.

Denver is the epicenter of the virus in Colorado.

As of Tuesday afternoon, 1,981 Denverites had tested positive for COVID-19 and 108 people had died, according to statistics from Denver Health. The curve is trending in the right, flat direction. But decisions by some cities and counties to open back up might undercut Denver's efforts to keep those numbers at least somewhat in check.

But there are no guarantees of an allied front.

Douglas County, for example, will probably follow the state's guidelines come April 27, County Commissioner Abe Laydon said, though no final decision has been made. He believes in the Colorado Department of Public Health's tiered approach to reopening and is boosted by revised projections from the White House predicting a lower death toll than originally thought.

"While we listened to good data, we need to make good public policy decisions that also reflect the externalities that all of our citizens are facing throughout the region," Laydon said. "So we're looking at really key metrics such as unemployment statistics and domestic violence and substance abuse and mental health issues, which are all competing with the need to stay at home and to be really careful about these public health measures."

Douglas County residents seem less at-risk of catching the virus than their neighbors in surrounding counties. State health statistics show the county, which is 47 percent open space, has the ninth-most known COVID-19 cases in the state, at 364. Laydon praised regionalism and said Douglas County would "leave that door open to have the conversation" with Denver and its other neighbors.

Boulder County, which parallels Douglas in terms of its infection rate, will have a decision on reopening to share Thursday morning.

"We are currently in discussions with our colleagues in neighboring counties, as well as the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, to determine the best course forward for our local communities," a spokesperson said. "We do not yet have adequate access to testing supplies, which is one of our considerations."

Denver's COVID-19 testing rate is subpar. Its strategy will evolve to include contact tracing and targeted testing.

Health officials agree that testing people for the respiratory disease and tracking infected people's contacts will be key to suppressing COVID-19's spread. Yet a little over a week until Denver's stay-at-home order expires, its testing rate is not up to snuff. The city's public health director, Bob McDonald, said Denver has "a ways to go" before it can administer the necessary 1,500 to 2,000 tests per week. Denver's weekly test results number in the hundreds, he said.

Mayor Hancock would not commit to reaching those goals before lifting his stay-at-home order, citing the possibility of more promising circumstances, which will probably only happen if Denver is able to team up with its neighbors on testing, said Cali Zimmerman, the emergency management coordinator for the Denver Department of Public Health and Environment.

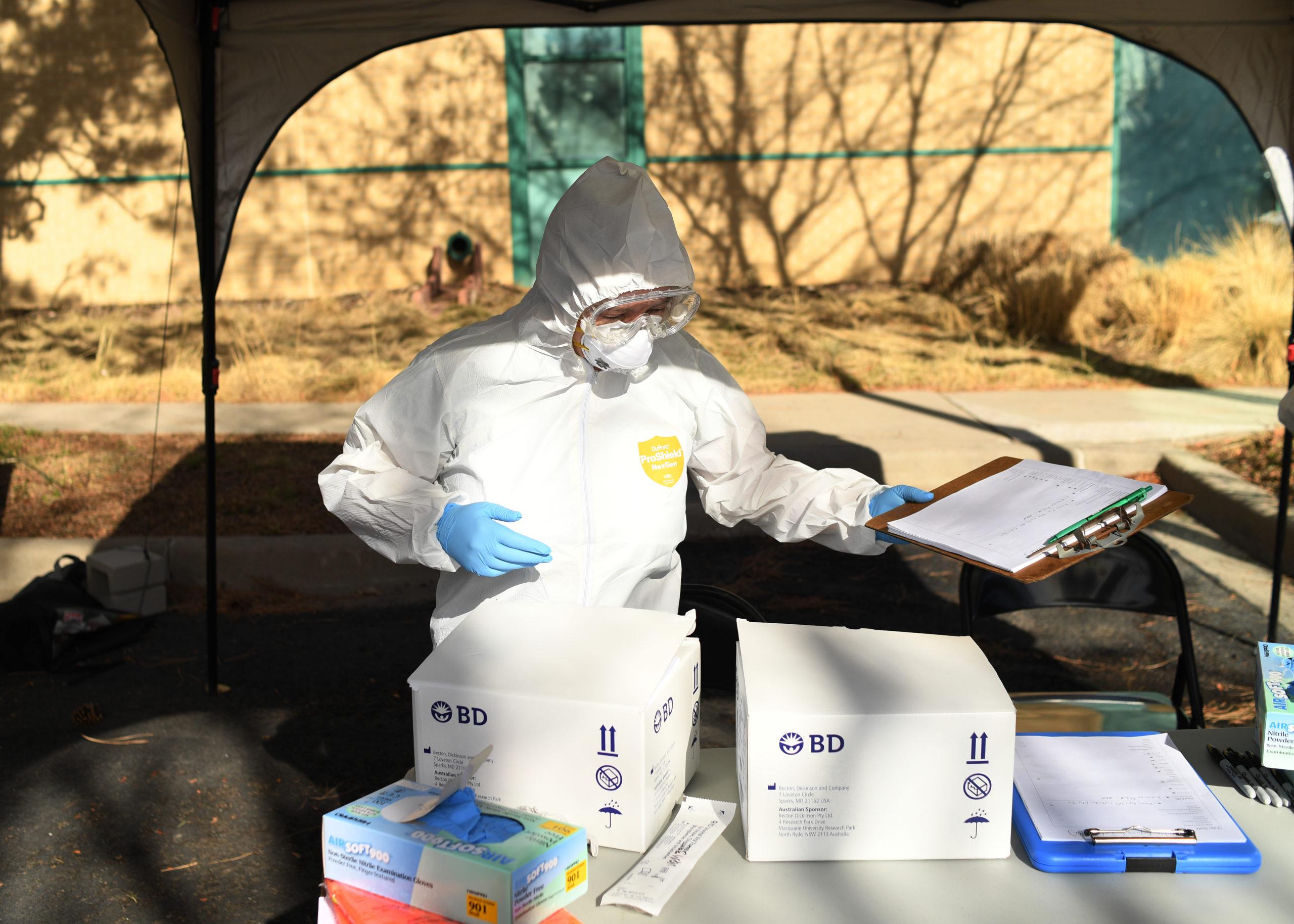

As the city prepares for the next phase, DDPHE aims to increase testing generally, target specific groups of people when necessary, and trace the contacts of infected people. But some health departments, including Denver, had been short on tests because of supply chain problems. In particularly short supply has been components of the "PCR" swab test that offers more rapid results and allows health workers to test targeted groups of people, like nursing home residents, at once.

"We don't have a ton of access to the testing supplies needed to both collect the sample and run the PCR testing on the lab side of things," Zimmerman said. "We're working with the other metro public health departments to come up with a strategy for the region and along the Front Range so that we're all providing similar access to testing for everybody in the area."

The city still does not have the capacity to test all the asymptomatic people it needs to. But Denver Health, the hospital that serves as the medical arm for the city's health department, is now stocked with tests for "congregant settings" like nursing homes, said Connie Price, the hospital's chief medical officer. Outpatients, inpatients and staff are also covered. Price is confident with Denver Health's abilities -- as long as things stay somewhat stable.

"We still have the capacity to probably double what we're doing right now," Price said. "There'll be a limit, but ... as we open up, we have plans to utilize that capacity. As long as COVID stays fairly stable and in control, we'll be able to accommodate that. If we have another surge, then, you know, that's a different story."

Aside from targeted testing, Denver health officials will gear up to track the contacts of up to 150 infected people per day.

Contact tracing -- or tracking people down who may have interacted with an infected person -- is on the table again after the city health department used the tactic early on in the pandemic. Now it's prepping to turn 150 city staffers into tracers, who will call and text infected people to find out who they've interacted with. Those who break their quarantine orders face a ticket or time in jail.

"If somebody is symptomatic right now and goes to a grocery store and puts a lot of people at risk, it's going to be a little bit harder for us to kind of trace that," Zimmerman said. "So what we'll rely on is building up our staff capacity to reach out and identify close contacts."

Denver's goals of regionalism and more testing won't matter much if people don't do their part, said Denver Health's Price.

Back in 1918, the city reopened the economy prematurely during the "Spanish Flu" after outcries from commercial interested and a cooped up public. Scientists charted the infections and the result resembled a camel: the first hump represented the initial outbreak and the second hump -- a larger hump -- depicted the second surge.

Zimmerman cautions comparing that time to today without caveats. Testing was different, communities were more insular, and scientific knowledge was far from where it is today, she said. But there is more than one similarity, including the common denominator of trying to control the movement of a lot of people.

"I think we can continue to be successful, but I worry that if people aren't 100 percent adherent to what the governor has really ordered, which was a tiered approach and opening up in a very structured manner -- if we don't abide by that, we really are at risk for having another wave," Price said. "This is not gone."