By 8 p.m. on Saturday, the start of the city's first curfew during massive protests against police brutality, word had gotten around that 10th Avenue and Sherman Street was the place to go if you needed help. As night fell, people -- many white, but not all -- crying and choking from tear gas began to arrive.

Street medics laid the protesters onto blankets and got to work. Some had real medical training, and others just had bottles of antacid.

Blocks away, police directed tear gas at angry protesters, including some who threw objects at police even as some protesters asked them not to. The day's peaceful protest over the death of George Floyd, which began at noon, was by now a distant memory.

One woman shrieked in pain. Her eyes had been covered by gas, and her contact lenses were pushed deep beneath her lids.

Jordan Rogell was running things at the camp.

"Where does it hurt?" he asked.

"Everywhere!" she screamed.

A few blocks over, another makeshift clinic was set up, in the courtyard of an apartment building that recently unionized to demand rent be canceled. Street medics rushed in and out of both sites, pouring antacid into people's eyes and and running toward the sounds of flash-bangs as they tried to offer protesters support.

People demonstrated in downtown Denver for hours a day, starting Thursday. The protests were largely peaceful, with people chanting, kneeling in front of police and calling out George Floyd's name. But some heckled or tossed things at police and police responded with tear gas, pepperballs, pepper spray, and flash bangs. After curfew, they used megaphones to tell people to disperse and then, advanced on the crowd, using chemicals to disperse them. In total, 45 people needed medical attention from professionals, according to Denver Health.

The camp at 10th and Sherman was set up by someone with no experience doing this kind of thing.

Police hit Dorian Gray -- no, not his real name, but it's what he goes by on the street and the only name friends know -- with tear gas on Thursday night. He said he was on his way to a corner store on Broadway when he accidentally entered the fray. He was thinking about the incident later that night when he felt a sudden urge to do something.

"I was really high on Thursday and I was watching it all go down from my friend's rooftop," he said. He told the friend: "We should set up a sanctuary at my apartment."

The Dorian Gray name is part of his persona as a member of Denver's "vampire court," a social club of cosplayers who like Victorian style and throwing huge parties. Several others helping out with the camp, like Rogell, are also members.

Gray is a software engineer who dabbles in paleontology and tends bar at Burning Man. He's never been a street medic before, but he said he has "a varied network of talented people" who are generally ready to help him act on projects quickly.

So he started making calls. In a few days, he'd collected hundreds of water bottles, supplies to combat the effects of tear gas, and kits containing goggles and masks to distribute to protesters. People sent money, too. By Saturday, he'd received about $1,500.

Anything left over after the upheaval subsides, he said, will be donated to the Struggle of Love Foundation, a Montbello group that runs a food pantry where he has volunteered.

On Friday night, Gray said he sat on his lawn until 3 a.m. in case any protesters came to the sanctuary on Poet's Row. They didn't arrive until Saturday.

As protests at the Capitol became more tense Saturday evening, Gray headed into the crowds. He and two women, who go by G. and Charlie, rushed toward explosions as people gagging from gas ran away. They held up spray bottles, yelling that they had neutralizer, and washed protesters' eyes.

They, too, were doused with gas. Gray and G. buckled over beneath the Capitol steps as snot and tears poured from their faces. But they bounced back quickly, springing up after the gagging subsided. They began yelling "Neutralizer!" again.

"God I love spicy food," Gray laughed as he headed back toward the line with police.

An existing network of Denver street medics has shown up at protests for years.

Vinnie Cervantes, a street medic himself, said he was grateful for the camp on Sherman. He headed out on Saturday with some other experienced medics but not much of a plan. Soon after they arrived, he began getting messages from his colleagues about the camp.

"Today was rough. A lot of tear gas and rubber bullets," he'd write his friends at the end of the night. "There were two different medic centers, which was really helpful and honestly dope because so many people were working to support them."

Cervantes has been working to establish street medics in Denver for the past few years. Members of his group, the Denver Alliance for Street Health Response, have been advocating for community-led responses to 911 calls about mental health crises that would otherwise be answered by armed officers. He sometimes patrols Capitol Hill, where he lives, to check on people living in homelessness.

He said he doesn't view his work during the current chaos as a form of protest. To him, it's more about broader community organizing. Any effort to make change that involves protest should include a medical element.

"It's community ownership of crisis or any other kind of struggle," he said, "using whatever skills or energy we have to help people who are inevitably going to be hurt by police."

Though he's been at it a while, on Saturday Cervantes said he'd never seen so many informal medics in one place. He was in awe of the turnout to Gray's camp.

"I've never seen it like this, ever. This is amazing. I'm really excited about it," he said. "A lot of the people who showed up are people I've never seen before. So there's just a lot of people getting engaged that just haven't in this way."

Gray said he was "thriving" while running supplies simply because he's an adrenaline junkie. One man retreating from the front line came up to thank him.

"I want to thank you, because y'all don't have to be out here with us," the man said as explosions went off in the background.

"Yes we do," Gray replied.

Gray said his girlfriends (he's polyamorous) have all but left him over his fervor. Both he and his primary partner are at high risk for serious illness if they catch COVID-19, and she's worried about him.

"That's been the biggest emotional stress," he said.

As the night dragged on, more people rushed to Gray's camp as he prepared to head back into the streets.

All kinds of people showed up at camp throughout the night. Some were familiar with the medics and wanted to lend a hand. Others needed help.

Rogell, the camp manager, fielded each one. He assigned jobs to new helpers, fetched supplies and lent a shoulder to people hobbling in.

"We knew that this would be our day," he said.

Medics dragged one man toward a blanket.

"Thank you for taking me," he said wearily. "All my friends had to leave. And thanks for grabbing my skateboard, too."

At 8 p.m., one medic yelled at the crowd: "If you cannot be arrested, now is the time to leave."

People with kids at home, she said, should go tend to their priorities. Things were going to get messy.

As protesters returned, the lawn began to buzz with rumors: One person said police had used a sound cannon to push protesters off the lawn in minutes. Another thought he saw a drone. Someone said journalists had been arrested. (None of these things have been confirmed.)

Michah Yahudah, a member of the local Black Panther Party chapter, said he'd spoken with officials who told him police would leave the field hospital alone so long as protests didn't break out there. Still, every time flashing lights passed after curfew, people ran off the sidewalk, believing it made them exempt from citation or arrest.

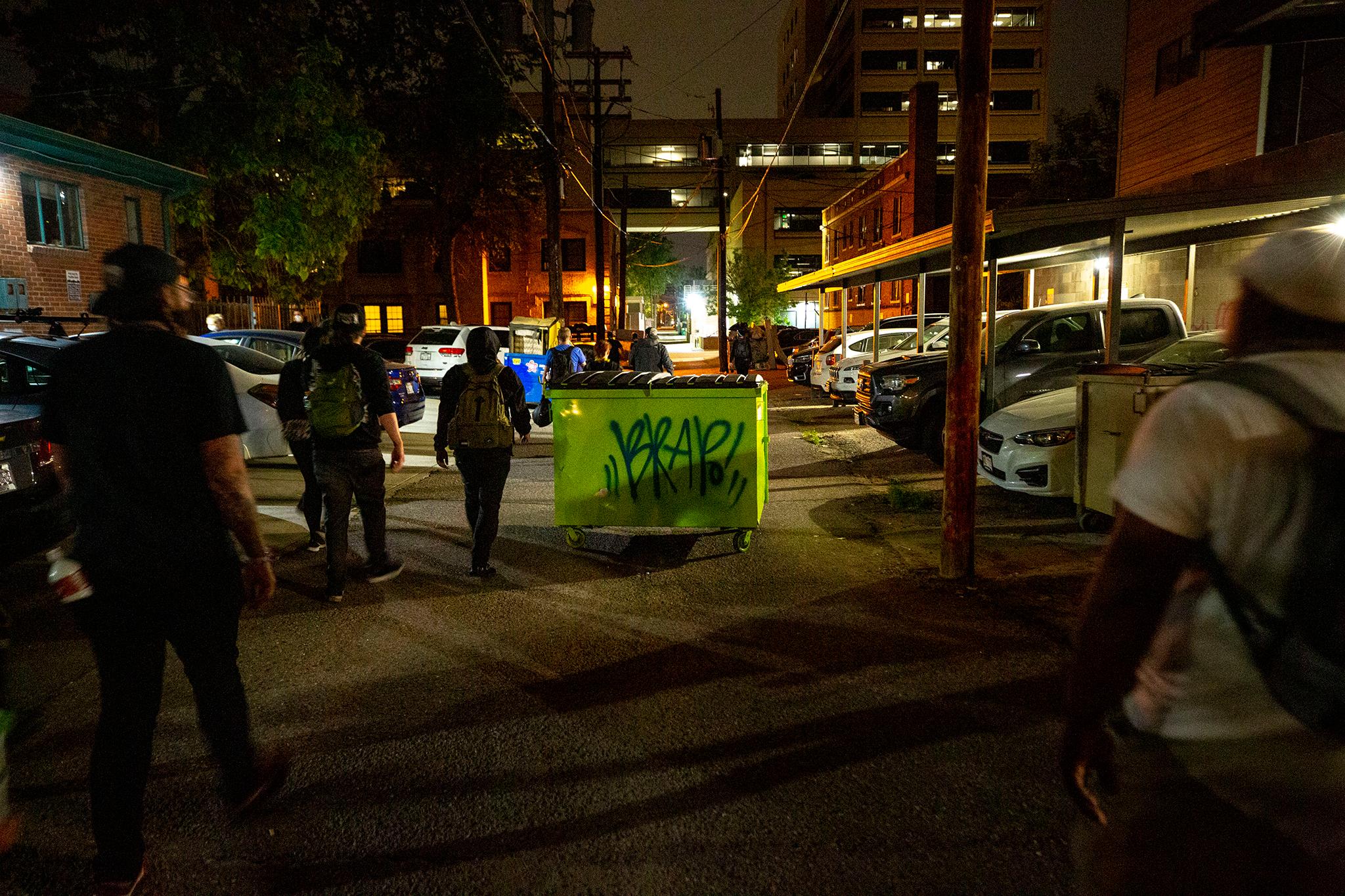

As things escalated, Gray, Yahuda and others made more antacid cocktails and packed bags to head back to the action. They took alleyways north toward Colfax Avenue. Crossing 14th Avenue, they saw the blaze of burning dumpsters a block over. When police approached, they began to jog. They moved dumpsters into the middle of the alley to deter any patrol cars that might follow.

Down the block, residents were hosing down a dumpster and mattresses behind their home.

"We just don't want our house to burn down," one said before wishing the street medics luck as they walked away.

The group ducked into a friend's place in an apartment building at 14th Avenue and Grant Street. They took a round of shots - whiskey - then Gray looked out the window. Below was the second field hospital. From his vantage point on the third floor, he could see people getting hosed down and rushing in and out of the gate. He had to get a closer look.

In this second camp, Paige Warren was yelling for people to get down and into the shadows. Police were everywhere, and she didn't want to draw attention that would end their efforts.

"Everybody stay out of the way," she yelled in the dark. "Sit down and stay out of the way!"

Warren said they'd treated about 40 people. Most needed treatment for tear gas, but others had bruises from projectiles that needed icing. One man needed more care. He hadn't eaten enough and collapsed, hitting his head on the pavement. An EMT on hand patched him up, and they gave the man some pizza.

Back in the apartment, Yahuda was talking shop with the other medics and protesters. He criticized the government "narrative" of events but admitted that he didn't like the violence he saw on the street. Attacking the library, someone said, helps no one.

He added that the Black Panthers have long preached that communities should police themselves. Protesters should root out bad behavior from within and combat violence.

He followed Gray and the other medics back into the alleyways.

They approached Colfax, where police were putting out a fire and shooting pepper bullets at protesters who lingered by the Cathedral Basilica. Antonio Smith came limping toward them, face covered with pepper spray.

Gray sat him down and instructed him to look down as he doused Smith's forehead with antacid. As it dripped into his eyes, Gray told him to blink it in.

Smith said he was glad to see the medics. They helped him recover quickly.

As for the police and the violence, he said: "It helps them to understand where we stand. The message out there is: We're not going to continue to tolerate you guys killing us. You three cops who stood there watching, you're just as guilty."

The large man's voice cracked as he spoke.

Gray and company decided it was time to head back to camp. One person said it wasn't "healthy" to stay out looking for trouble. Plus, Gray thought, Rogell and the others might need some help.

They dodged officers on the way back, creeping toward alleyways. On 14th, a group of protesters ran past and spotted the dumpsters in the street, which had been extinguished and abandoned.

"Let's burn them!" one of them shouted.

Across the street, another group of protesters spotted a FOX31 vehicle. Someone else ran to the SUV with a rock, shattering its windows.

As they crossed 13th, they spotted someone inside Pub on Penn leering out through the glass.

A fire truck passed as they headed south. A firefighter waved as they passed.

"Thank you for your service!" one of the medics shouted.

Along the way, they passed several apartment buildings where people were handing out water and had what they needed to help with tear gas. In front of one, a man yelled that the group should go to 10th and Sherman if they needed anything.

When Gray and his friends made it back, Poet's Row was nearly silent. Someone was sleeping on the other side of a window, and the traffic had died down. Two men sat smoking joints against a tree. One, who said his name is Ananse Kuumma, was grateful.

"It's nice to have someplace to rest."