The pandemic continues to threaten Denver's "micro businesses," the smallest outfits whose owners often see themselves as defining the fabric of the city.

That's how Millete Birhanemaskel describes Whittier Cafe, the business that she's managed to keep open even as she halted dine-in operations and stay-at-home rules meant few customers would venture into her storefront on 25th Avenue. In normal times, Whittier Cafe is a gathering place, usually packed with people churning over new ideas and local leaders meeting the people they serve.

Birhanemaskel knows what it's like to rely on a paycheck, so she prioritized keeping her employees on the books as the situation got difficult. Once things "hit the fan," she estimated she could last three or four pay cycles. Beyond that, she'd need supplemental funding to keep her rent and staff paid.

She applied for the first round of emergency grants from the city, which continues to offer up to $7,500 to businesses impacted by COVID-19.

Weeks passed without word on a decision. Then, almost two months after she applied, she got a letter. Whittier Cafe didn't make the first round because, she said, her projected losses weren't as significant as other applicants. It felt like a gut-punch, as if the city told her: "Your pain isn't bad enough," she said.

"I was not feeling supported in a very stressful time, in a neighborhood that I think we play an important role in," she said. "To get that letter that was all nonchalant eight weeks later, I was frustrated."

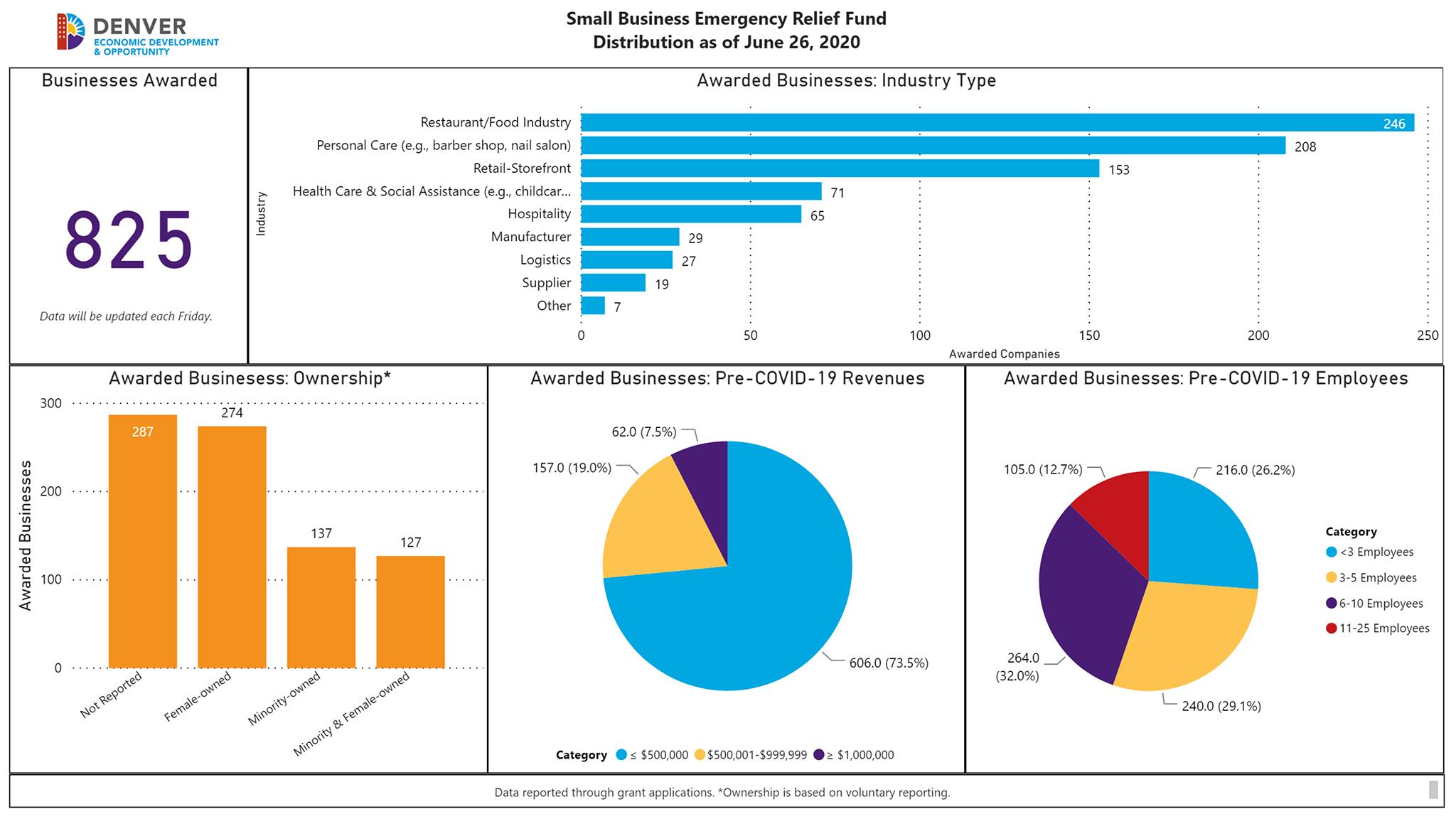

Denver announced its third round of COVID grants at the end of June. So far, the city has doled out emergency funds to 825 businesses. But as officials attempt to keep the economy afloat during the pandemic, some business owners like Birhanemaskel are concerned its efforts won't be enough for small, community-oriented operations to survive.

Kevin J. Beaty/Denverite

Some owners have given up on the fund entirely.

Though she is eligible to apply again, Birhanemaskel said a "ridiculous process" and her bad experience led her to give up the emergency fund altogether. After she penned a Facebook post expressing her frustration, she began receiving checks from customers who felt moved to share their federal assistance checks. That money, plus a loan from the federal Small Business Administration, helped her get through the slowest times. She just wishes Denver officials shared her customers' urgency to keep a place like hers afloat.

"The city is completely clueless as to what businesses are making the city go, that make up the fabric of this community," she said. "Ultimately, what saved us was community."

When Denverite spoke to Hope Tank owner Erika Righter in March, she made it clear the pandemic was worsening existing pressures that micro businesses like hers have faced for years. Growing commercial rent prices had piled up long before COVID-19, so when customers disappeared from her stretch of Broadway, the prospect of making it through to a new normal felt extremely difficult.

Righter was denied an emergency grant the first time she applied. So she applied again and again. She finally made the third round. Denver awarded Hope Tank the maximum $7,500.

But Righter said she knows business owners who became discouraged after their first denial and, like Birhanemaskel, gave up.

"They all stopped applying," she said. "The experience is humiliating. You have to prove how bad things are."

A city spokesperson said over 3,700 applicants have tried to access the program since the first round opened in March.

Who will make it out of this moment intact?

City Councilwoman Candi CdeBaca has been trying to see how much money, exactly, has been flowing from this program since the first round of recipients was announced in April. But the Denver Office of Economic Development has refused to share that information with her or with Denverite when we asked, saying it would reveal business losses and is therefore confidential.

For CdeBaca, transparency is deeply tied to concerns about equity. She'd like the grant program to prioritize businesses that already face gentrification and help define the neighborhoods where they're located. In her worst-case scenario, the pandemic downturn could flush small operations like Whittier Cafe from Denver's streets, only to be replaced by companies with more capital and fewer ties to neighbors.

"This is an incredible opportunity for people who had assets to begin with to swoop in and dominate every sector," she said.

According to the city's numbers, 65 percent of awarded businesses self-identified as "female-owned," "minority-owned" or "minority and female-owned." Over 70 percent of recipients reported annual revenues below $500,000.

But CdeBaca said she remains skeptical because she can't see how much money actually flowed to these recipients. Her frustration plays into an effort she and her colleagues have started to change the city charter to give Council more power over departments that currently "unilaterally" answer to the mayor.

"A lot of what's happening, and even the transparency, is because we have no control or semblance of partnership over the agencies," she said.

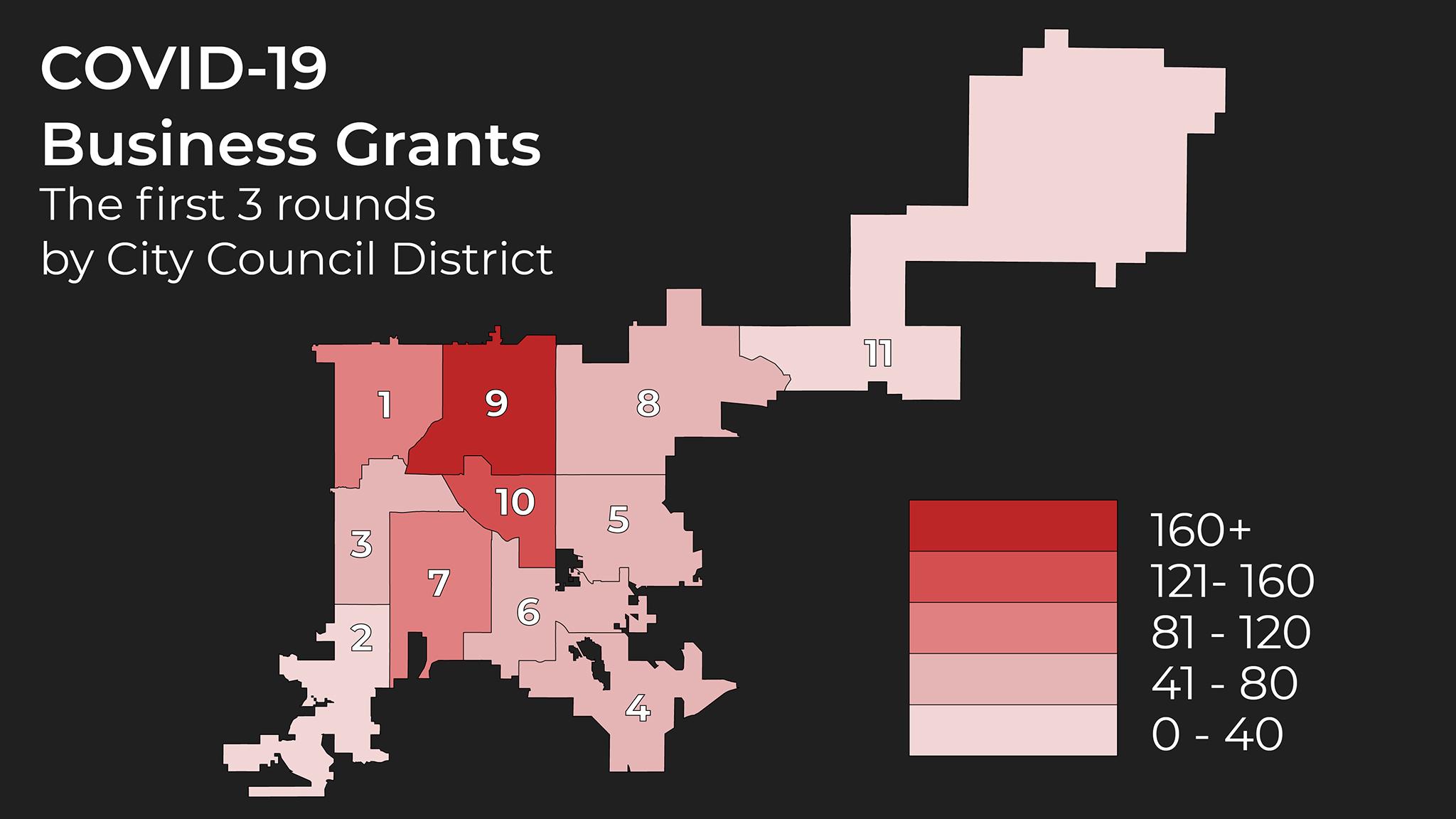

The majority of grants, 192, have been distributed to companies based in CdeBaca's District 9, which includes Whittier Cafe, downtown and the RiNo Art District. District 11, which encompasses far northeast Denver and is home to many residents of color, only received 29.

Data source: Denver Office of Economic Development and Opportunity

In May, Righter conducted a survey of 65 business owners to see how people were faring. Eighty-five percent said the city had not given them enough information or tools to "safely re-open."

When asked what Denver's leaders could do to show more support for small businesses, responses ranged from "I have no idea at this point" to "I don't think they fully understand the long-term impact."

"If we could get relief on bills, that would be the biggest help," one respondent wrote. "As of now we are still paying our bills without a penny of relief and that has been really painful. If we're going to get through this, we need help or we're going to be faced with one hell of a hard decision. I don't know how realistic that is, but it's what we need. And it all starts with being heard."

Still, small-business owners that fit the "community-oriented" description have received emergency grants and were happy for the help.

Kevin J. Beaty/Denverite

Martha Jamieson, who runs a piñata shop on Federal Boulevard, said she was awarded $5,000, "a lot of help" to make rent after she had to shut down. When she spoke to us in April, she was still waiting to hear if she'd made the cut.

"It worked out a lot better than I thought," she said recently. "I was worried about it."

In March, Sylvester Osei-Fordwuo was wringing his hands over African Grill and Bar, which he co-owns with his wife, Theodora. Sales had all but halted in his Green Valley Ranch location, and the mortgage on their new, much bigger location in Lakewood was cause for deep concern.

But Osei-Fordwuo said he also received emergency money from the city, and he was grateful. Like Righter, African Grill also got the full $7,500. But, he added: "The rent is $7,000."

While Righter said the $7,500 will help correct the $70,000 deficit she's found herself in, she would like to see the city do more. It's not just about money, she said. It's about leadership.

Before she spent $500 on masks (which she later learned were defective) and before she raised money to buy plywood to cover her windows and pay artists to adorn them with murals, Righter said the city could have "leveraged" its relationships with large corporations and suppliers to lend a hand. She wondered if a company like Home Depot, for instance, could have donated supplies.

More than a shortage of customers, her debt reflects everything else she must buy to keep herself, her business and her customers safe.

"Expecting the city to do all of this is unreasonable," she said, "but it is reasonable for the mayor's office to call publicly on corporations who have benefited greatly from his administration to pony up."

Kevin J. Beaty/Denverite

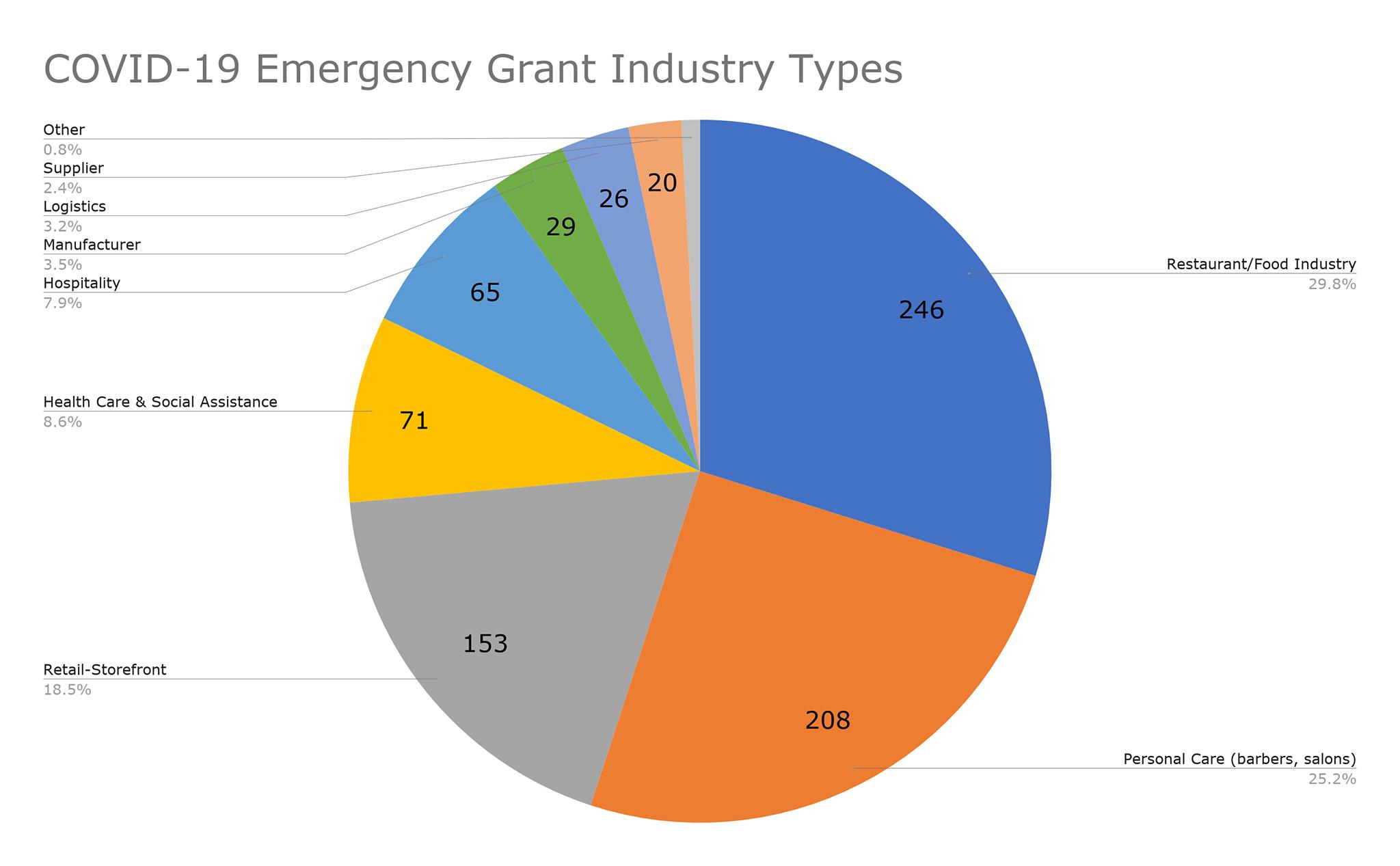

She'd also like officials to speak up for small retail operations like hers. The way she sees it, Denver spent most of its time focused on food service. Only restaurants, for instance, are currently allowed to apply to use parking spaces and sidewalks to expand their spaces as the city re-opens. Righter said stores like hers are being left in the dust.

"I want to see a campaign around local spending, separate and apart from food and booze and weed," she said. "I want to see actual plans of how that's going to happen."

Almost a third of emergency grants were awarded to restaurants and other food-adjacent operations. Retail accounted for just under 20 percent.

Righter said it's not too late for something like this to come to fruition. She stressed that proprietors like her are still a long way from making it out from the pandemic's long shadow. A single grant will only cover so much rent.

"I'm grateful that we're open, but now people have this impression that -- check! -- yeah, we're good," she said. "No."

Many of her customers are likely still dealing with the COVD-19-caused recession. While Denver isn't seeing as many new cases as it was in April, recent numbers show infections have begun to rise slightly again.

Business owners like Righter and Birhanemaskel hope authorities won't let them disappear as the crisis drags on.

"The city needs to do a better job if they're doling out community dollars," Birhanemaskel said, "to understand what the community wants and what's important to the community."