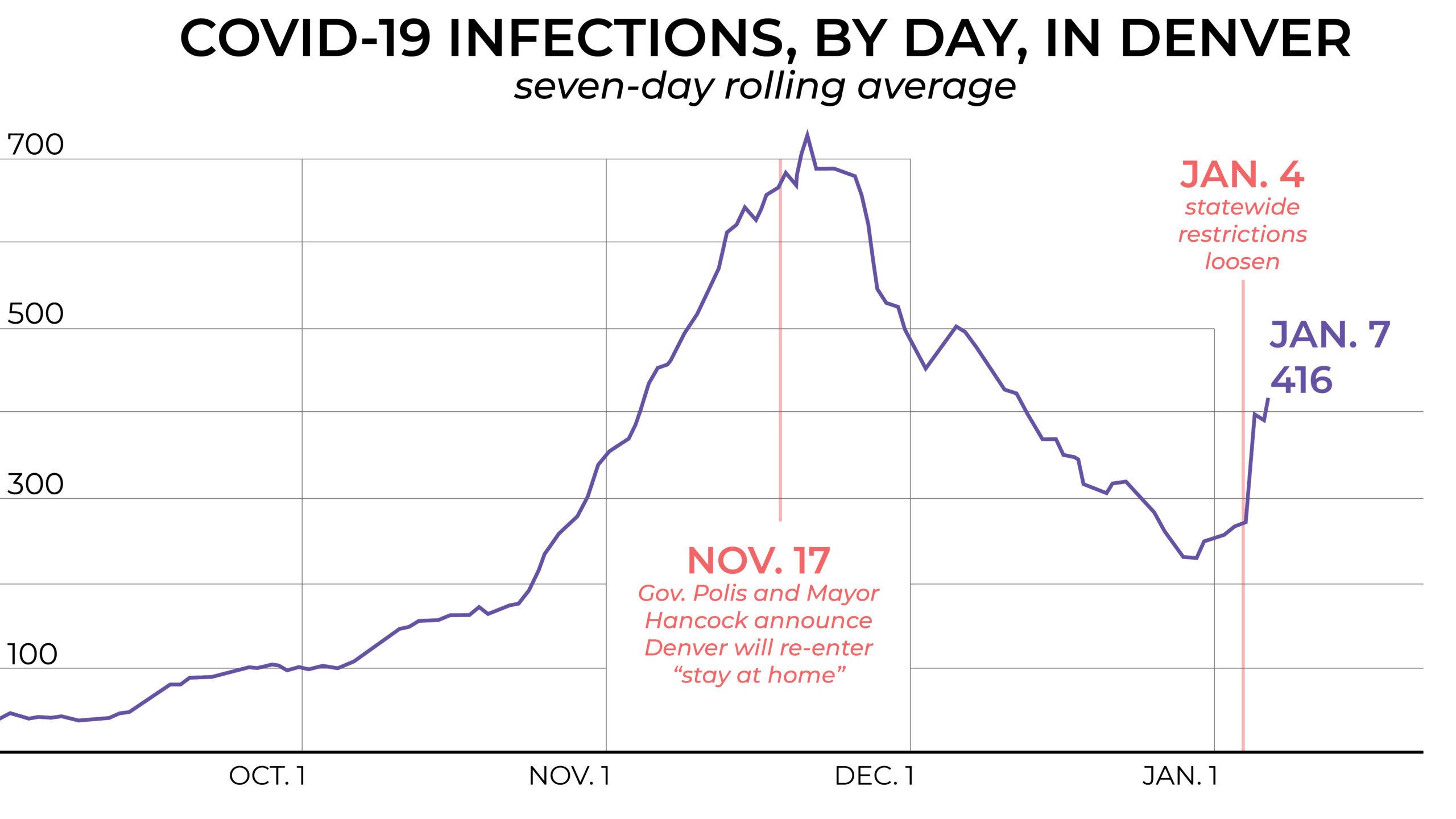

COVID-19 infection rates were on the steady decline in Denver after reaching record highs last fall. But the city is now experiencing an uptick in cases, and it's likely related to the holidays.

Denver saw fewer than 250 positive tests on a single day until mid-October, when those numbers more than quadrupled in just a month. The single-day count peaked Nov. 21 at 1,014 new cases. But new infections began to drop from there, nearly as quickly as they rose.

That trend ended Tuesday. On Jan. 5, the state recorded 1,043 new cases in Denver. On the previous day, just 172 new infections were recorded. Jan. 4 also happened to be the first day restaurants were allowed to re-open in Denver, and elsewhere in Colorado, after Gov. Polis eased restrictions.

"We have unfortunately seen an uptick in cases, and it's most likely attributed to holiday gatherings," read a prepared statement in an email from the state's Joint Information Center, which did not specify who wrote the message. "It's too soon to tell if it's just a momentary increase or if it's an indication of a more significant, sustained spike."

Those "holiday gatherings" include Christmas, Hanukkah and Kwanzaa. In a press conference on Jan. 8, state epidemiologist Dr. Rachel Herlihy said it was too early to know whether transmission during New Years Eve celebrations will prolong the spike.

Below is the latest two-week-cumulative figures from Denver. Each point on the graph represents new infections per 100,000 people logged on that day, plus every other day for two weeks prior.

The following graph updates every day. Click here to see an interactive version of it.

Worth noting: These numbers don't represent every single case in Denver, just every case we know about. People won't show up here unless they get a positive test.

Also worth noting: The number of people tested on a single day impacts these numbers. During the press conference on Friday, Gov. Polis said many people weren't tested over the holidays, so the new record set on Jan. 5 was probably an over-correction once people finished their end-of-year celebrations. Still, Denver's positivity rate - the ratio of tests taken compared to tests that came back positive - grew in the last week, which means the spike is about more than people rushing to get their nostrils swabbed.

The following graph updates every day. Click here to see an interactive version of it.

The holiday spike occurred just as Denver and Colorado began to loosen restrictions.

Health officials around the state were caught by surprise on the evening of Dec. 30, when Polis announced that he was easing statewide rules to keep the virus from spreading.

He said counties with the tightest restrictions according to Colorado's COVID dial would be downgraded. That included Denver. For example, beginning Jan. 4, restaurants were allowed to host in-person dining again.

In December, Denver County saw about 350 cases on average each day. New positive tests dipped as low as 115 on a single day during the holidays. Then, on Jan. 5, the state logged 1,043 cases in Denver.

The state said loosening restrictions was still the right move, despite the holiday spike and the fact that Denver recently saw twice as many new infections compared to any time over the spring and summer.

"Our goal is to empower counties to operate with the least restrictions possible, while at the same time ensuring protection of the public's health and Colorado's hospital capacity," another statement from the state's Joint Information Center says. "We are closely monitoring disease transmission while working to provide much-needed economic relief by allowing businesses to operate with fewer restrictions. We need Coloradans to continue to follow public health protocols until vaccines are widely available and community immunity is achieved. It's important to continue to wear a mask, practice physical distancing, and avoid large gatherings. Colorado hasn't finished this marathon yet, and we want to ensure our hospitals are never overwhelmed."

Tammy Vigil, a spokesperson with the Denver Department of Public Health and Environment, said city officials are also comfortable with fewer restrictions.

"While daily case counts are generally higher than they were in the spring, we now know much more about controlling transmission, treating the disease, and important key metrics to monitor," Vigil wrote in an email to Denverite. "DDPHE is working closely with the state to loosen restrictions whenever possible, but also closely monitoring and responding to key COVID metrics."

In his press conference on Friday, Polis said hospitalizations had dropped enough that counties could move away from the "really restrictive" measures. Before Monday, in-person dining and gathering with anyone from outside of your household was banned, last call for alcohol on patios ended at 8 p.m. and gyms were only allowed to fill up to 10 percent capacity. That was "level red," AKA "stay at home."

We're now at "level orange," also known as "strongly advised to stay at home," which eases the items listed above and more. Polis said that when he makes a decision on restrictions, he has to weigh the risk of the virus itself against the pandemic's economic and psychological tolls.

"We as a state have always sought to balance the impact," he said.

But Maggie Gomez, deputy director with the Colorado-based Center for Health Progress, a group that connects service providers with people who need them, said she worries fewer restrictions will put communities of color and low-income residents at risk, since they are more likely to work in jobs that can't be done at home. Cities and states are forced to make dangerous decisions, she said, because the federal government hasn't provided the kind of money that would make it easier for people to stay home and avoid catching the virus.

"We want these small businesses to survive. We also want people to live," she said. "It's really important that we do prioritize the health of people over business."

Gomez was a member of several committees that Polis created early on in the pandemic to work on access to testing, aid and vaccines, so she knows how things work inside the state's health department, she said. While she's "confident" some of Colorado's best minds are working to strike the balance between infections, economics and mental health, she said she's not convinced policy changes have followed the numbers. She sees a direct line between loosened restrictions and greater risk for people who can't work from home.

"The data is great, and we actually need to use it," she said. "What I'm worried about is that we're not using the data in a way that is equitable."