In recent months, Union Station has been depicted as a hotbed of violence and drug-dealing. Neighbors and bus drivers have said they feel unsafe. At least one business has shut down over crime.

In December, at the height of public outcry over the issues, Denverite spent 18 hours at Union Station and saw a different story: Unhoused people sleeping, security trying to keep them awake, some doing drugs, many trying to stay warm, and plenty in a state of mental duress. Travelers and transit-users also shared the space -- some having the time of their lives.

The Lower Downtown Neighborhood Association's Safe, Clean and Compassionate committee spent the winter trying to rally Mayor Michael Hancock, the Regional Transportation District and the Denver Police Department to beef up social services, security and law enforcement patrols, asking police to make more arrests.

The city took action. In late March, Mayor Michael Hancock and city brass stood above the Union Station bus concourse and boasted about police making more than 700 arrests in the area -- a response to public complaints about crime. By the end of April, the number had ballooned to 932 in the neighborhood, and the city was on track to arrest 1,000 by the end of May.

"This is not about housing or homelessness," Hancock said in late March, when asked about the many people carrying their possessions with them and shrouded in blankets to stay warm. "What we are seeing here is not homelessness. This is about the sale and use of deadly illegal drugs."

Heading into an election season, in an era when tough-on-crime politics are en vogue and Democrats are rolling back criminal justice reforms related to substance use and resuscitating War on Drugs rhetoric, Hancock -- who is term limited -- pointed to the arrest numbers to show that his administration isn't coddling people who are breaking the law.

But arrests, argue addiction specialists, are not effective in addressing a drug crisis and make matters worse. They say housing and social services are needed instead.

Hancock assured the public that his administration is sending not just cops to Union Station, but also social service and outreach workers. They address unhoused people's needs and attempt to get drug-dependent people into treatment.

Denverite dove into the available data on arrests and social services offered at Union Station to better understand the administration's approach to solving the area's issues.

To get to the more than 700 arrests Hancock boasted between January 1 and the end of March, Denver Police Department tallied every arrest in the Union Station neighborhood -- not just at the Great Hall or the bus concourse.

Of the 932 arrests tallied between January and the end of April in the neighborhood, 696 occurred within a half-block of Union Station.

The Denver Union Station Alliance, the private company that leases the publicly funded Great Hall, argued this criminal activity isn't happening inside their plush space, also known as "Denver's living room." That living room -- once billed as a public place -- has become increasingly privatized in recent months. Guards ensure bathrooms are restricted to paying customers, and media has been barred from videotaping or audio recording without permission inside the building which was renovated with taxpayer money.

"The Denver Union Station Alliance, the entity which leases and operates the historic building, takes tremendous pride in providing a safe and enjoyable experience for all guests, associates, and the community though our full-time independently contracted security team as well as through our partnership with RTD and the Denver Police Department," according to a Denver Union Station statement.

"The ongoing issues are taking place in the RTD transit spaces, not inside the historic building," added Union Station spokesperson Julie Dunn in an email.

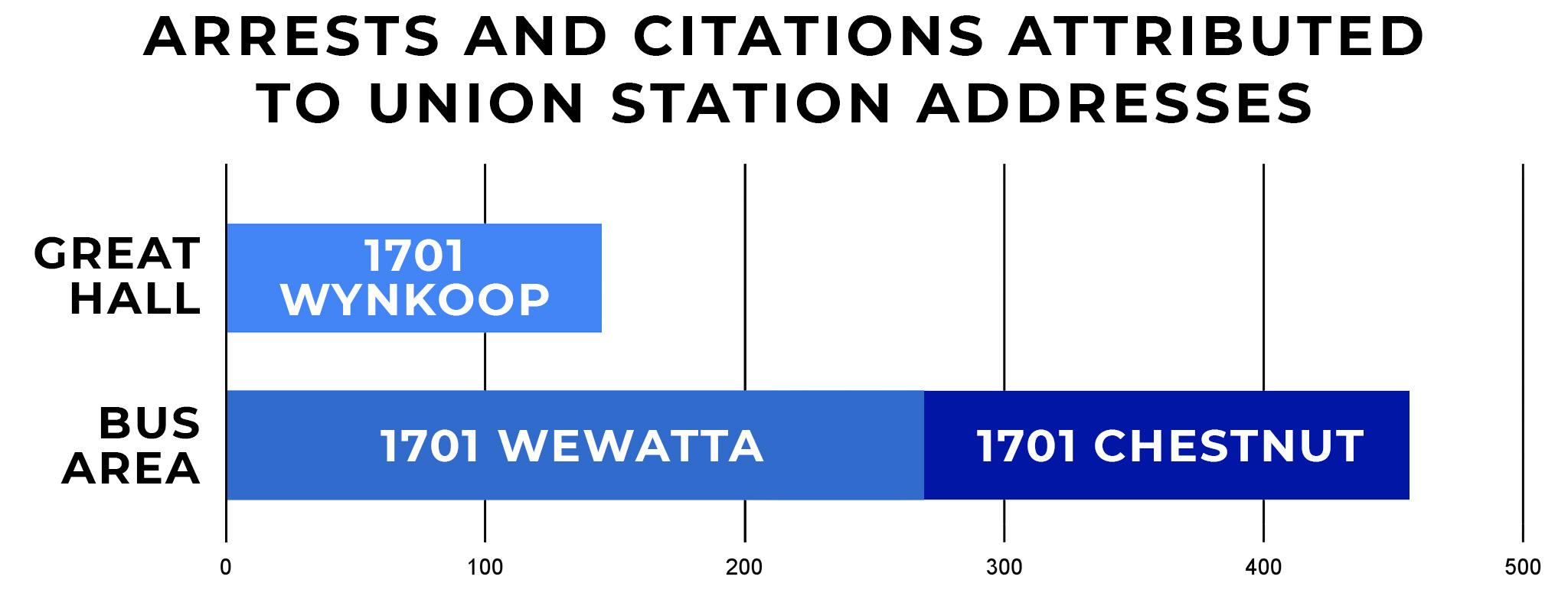

The data provided by the Denver Police Department doesn't bear that out. At 1701 Wynkoop St., the Great Hall's address, DPD tallied 145 arrests.

At the RTD bus concourse, at 1701 and 1700 Wewatta St. and 1701 and 1700 Chestnut Pl., DPD tallied 465 arrests. Those contacts prompted RTD to make a number of environmental changes to the facility, including removing or restricting access to outdoor benches; fencing off park space and sections of the plaza above the concourse; removing electrical outlets passengers use for charging phones; improving lighting; and eventually installing a turnstile-like system to limit access to paying customers only. Progress on those changes can be found at RTD's website.

What were people arrested for?

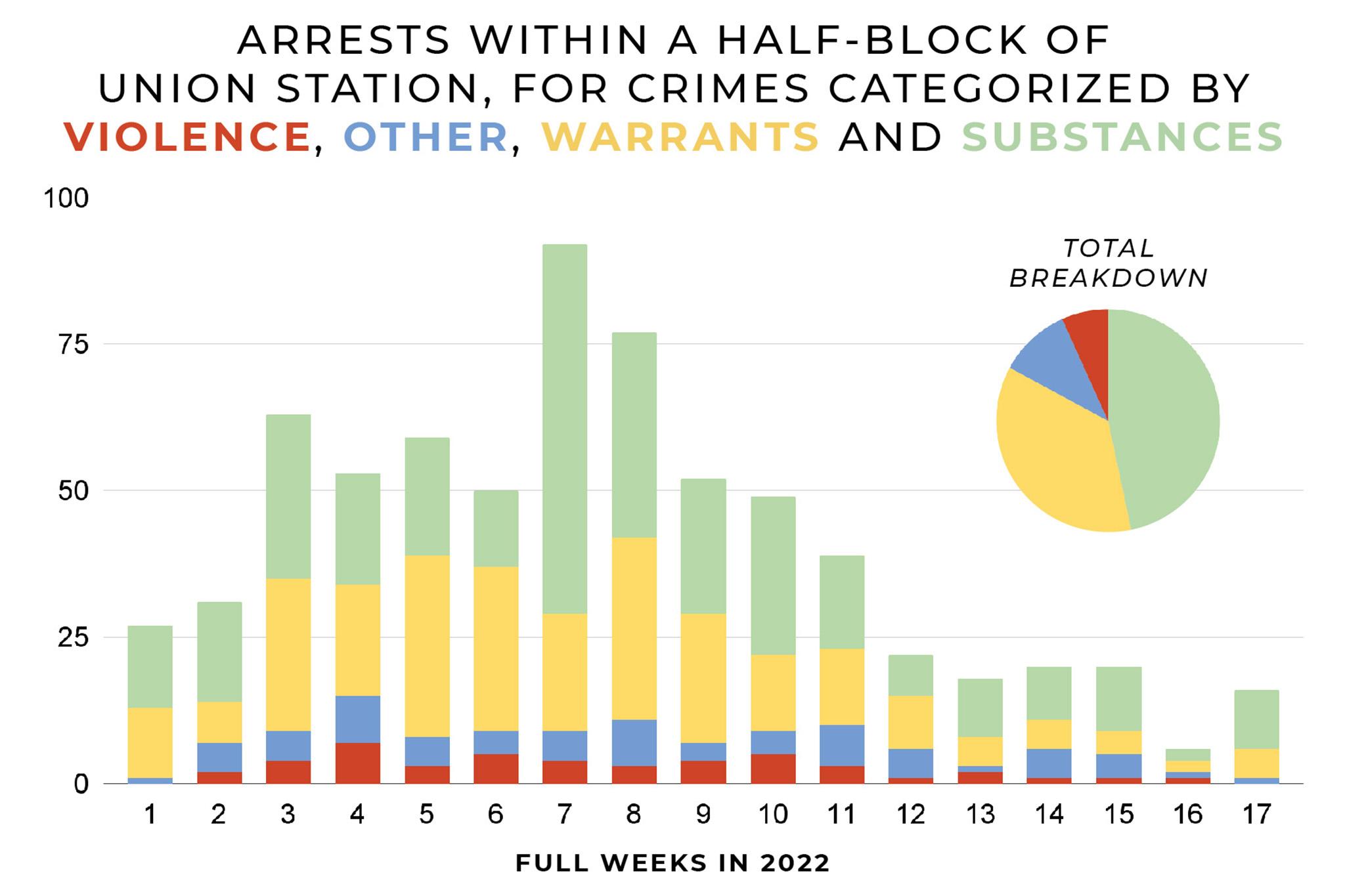

While the headlines about Union Station make it sound like a dangerous place, violent crimes recorded within a half-block radius of its buildings made up just 47 arrests from the beginning of the year through the end of April, or 6% of charges.

The most common charges, which made up about 46% of all tallied near the station, were related to substance possession, use or distribution. Charges related to open warrants accounted for 36% of the total. Other crimes, including trespassing, destruction of property and violations of court orders, accounted for 10% of the total.

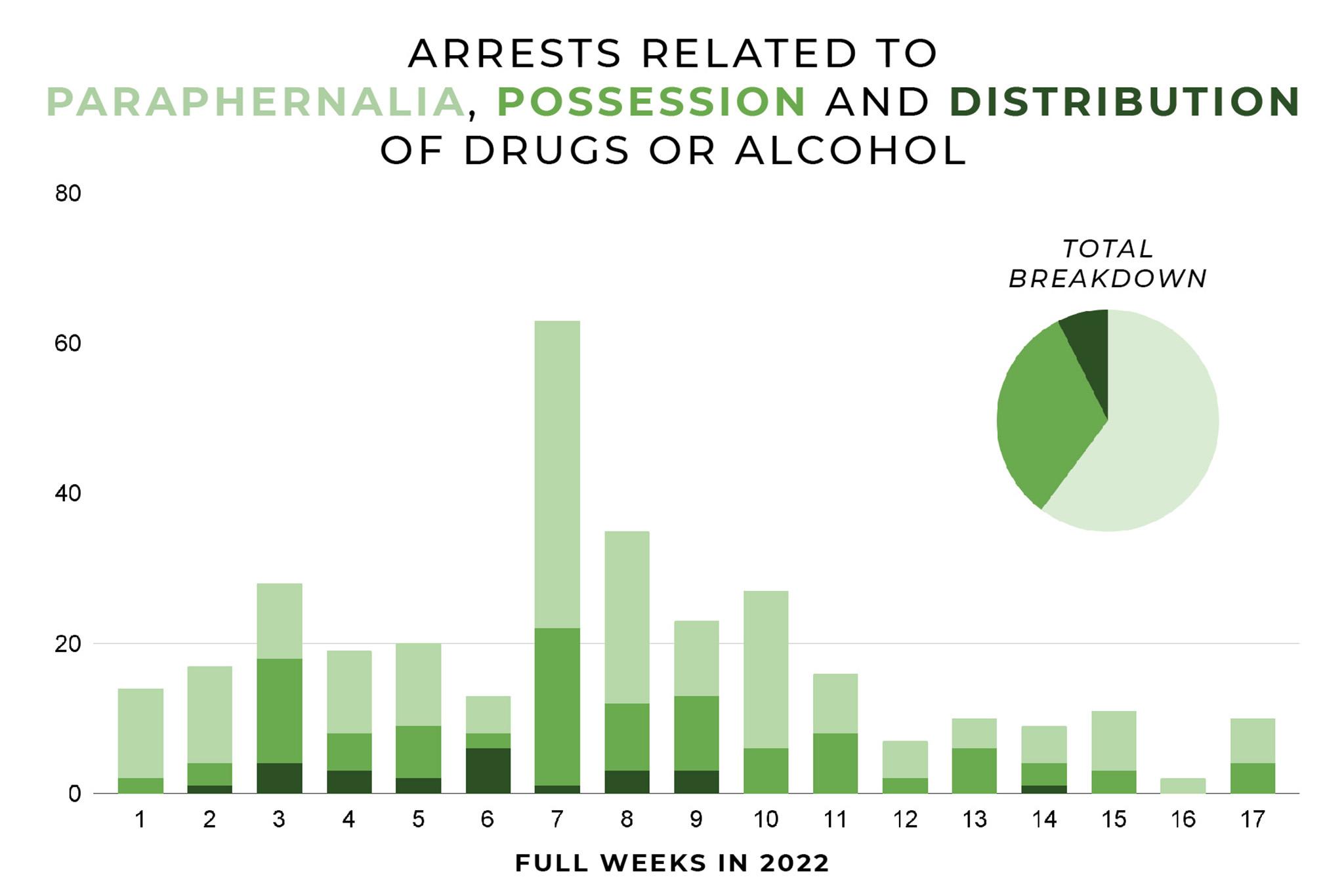

The mayor acknowledged drugs are the main crime issue in Union Station, and the arrest data backs that up. But is the city taking down dangerous drug dealers, as Hancock has suggested, not people dependent on drugs?

Of all the substance crimes recorded at or near Union Station, 60% were paraphernalia charges, 32% were for possession, and 7% were labeled with "distribution."

So what is an arrest, anyhow, and do they all lead to jail?

Denver Police Department arrest tallies include both people who have been booked in jail and people who were simply detained, ticketed and perhaps removed from the premises.

DPD data show 471 of all 696 arrests led to bookings, and 225 led to citations without jail time.

Arrests without booking give police an opportunity to intervene when people are engaged in minor crimes without going through the full rigmarole of jailing them, and it allows officers to legally remove people committing certain crimes from the premises.

But it also means that people receive tickets for charges like drug paraphernalia -- sometimes for as little as $50. Some of those tickets never get paid and lead to warrants. Outstanding warrants lead to more arrests.

Were people arrested multiple times?

Most people, 379, were arrested just once. All but five of those were charged with one crime. Of those crimes, 155 were related to substance use, possession or distribution; 153 were for open warrants; 51 were for other crimes like trespassing, property destruction and the improper use of credit cards; and 25 were for acts of violence.

There were 115 people who were arrested more than once, including 43 people who were arrested three or more times.

Of the 115 people who had more than one arrest, nine were charged with a violent crime, 92 received substance-related charges, and three people were cited twice for trespassing.

Arrests are dropping. Why?

Arrests spiked in the seventh full week of the year, from Feb. 14th to Feb. 20th, and began to gradually decline. By week 12, March 22-27, crimes dropped below 25 per week.

While there are still an abnormal number of arrests in the area, the numbers may suggest crime -- or at least reported crime -- is down. Denver Police Department spokesperson Jay Casillas said there is no single explanation for the drop, but the department has a few theories.

"A variety of reasons including officer intervention, partnerships with the community, as well as weather can play a role in the reduction," he said. "Some data that reflects the decline is calls for service from citizens. In January 2022, there were about 436 calls for service in that area. April of 2022 there was 326 calls for service. Even though there is a downward trend in arrests and reported crime, officers will continue to patrol this area to address any issues."

The administration is using both social services and police to address the issues at Union Station. But the numbers show that arrests are far more common than offers of services. In April, the city upped its social service efforts.

Denver Department of Public Health and Environment's much-touted Support Team Assisted Response unit, better known as the STAR program, shows up for mental health emergencies and other crises in lieu of law enforcement. That group has had 35 responses in the Union Station area from January 1 to the end of April.

The Substance Use Navigator co-responder program, which shows up with police and the Department of Housing Stability's Early Intervention Team when requested, connected with 34 individuals from January 1 to the end of April. Seven of those people were referred to treatment or were being revisited by the team for a follow-up appointment. That team typically distributes harm-reduction supplies like the overdose-reversal drug naloxone and fentanyl testing strips, to ensure drugs aren't laced with the deadly synthetic opioid that has contaminated much of the drug supply and led to a rise in overdoses.

Then there is the Wellness Winnie, a mobile behavioral health unit staffed with peer navigators, the Department of Housing Stability's Early Intervention Team, and counselors, that roams the city, offering mental-health services and other support.

"Beginning in mid-April, the Wellness Winnie team, along with some other city partners, began spending one day per week at Union Station as part of a pilot to provide resources in that area," wrote Denver Department of Public Health and Environment spokesperson Emily Williams in an email. "So far, the Wellness Winnie team has connected with over 120 individuals over the course of 4 separate visits to Union Station."

Its ramped-up presence coincides with a drop in arrests, suggesting addiction experts might be right: Even a small investment in social services could have a large impact on reducing crime.