It's been a month since Denver officials hastily turned a rec center into an emergency shelter for busloads of migrants and asylum seekers, mostly Venezuelans, who've been coming from southern U.S. border communities overwhelmed by humanitarian need.

In that time, Denver has spent more than $1 million on facilities, staffing and food. Officials opened a second overnight shelter at another rec center and moved people into motels, all while housing locals from an extremely cold winter storm.

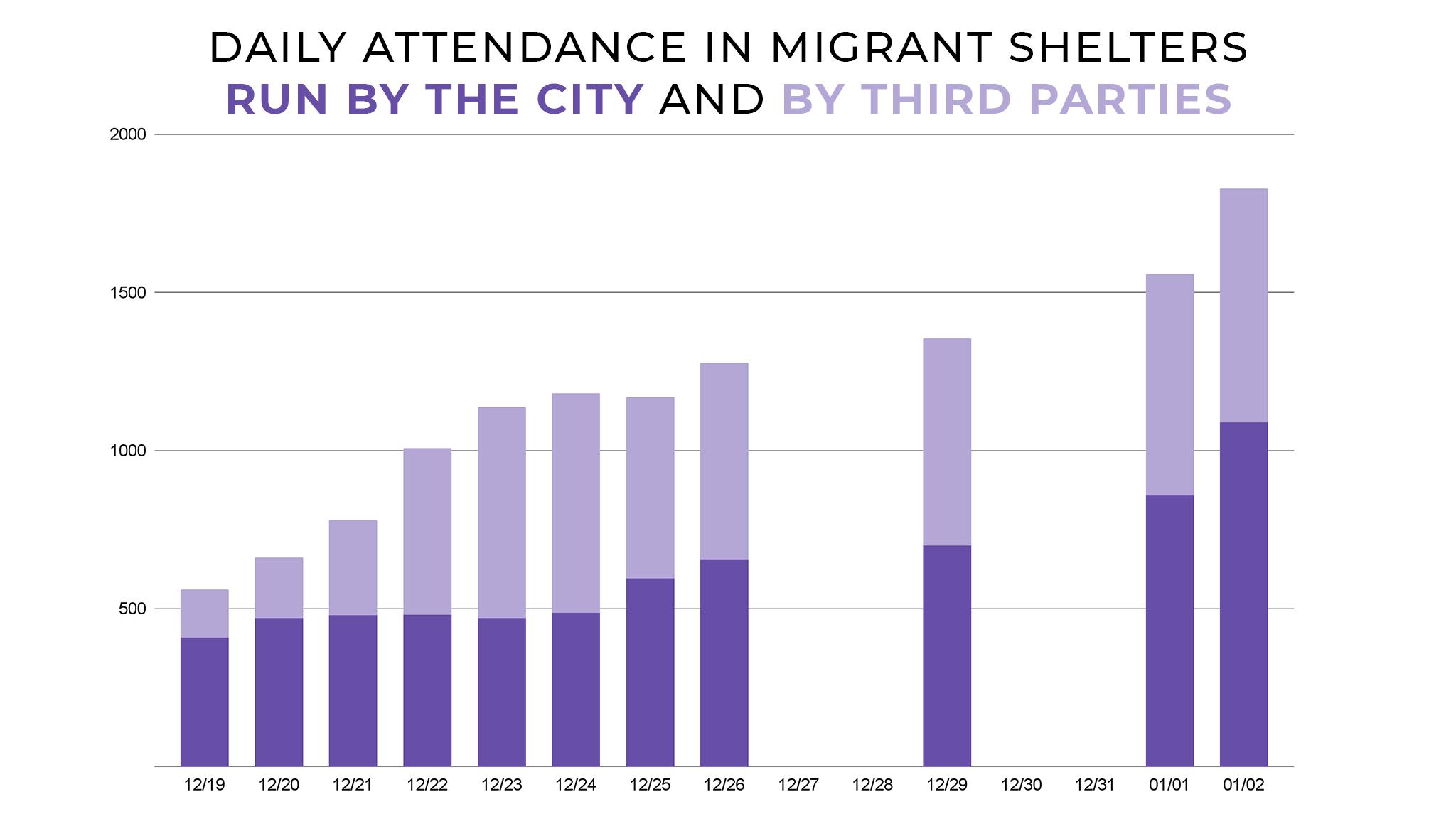

The number of migrants sleeping in city-affiliated beds has risen over 200% in the last two weeks. As of Tuesday, it was more than 1,800 people, putting the demand on par with what Denver's homeless shelter system regularly gets. Mayor Michael Hancock has said the city is running out of capacity to help. His staff and allied community organizers are trying to move this response into a new phase, something more sustainable, but it's going to take work.

"It's important actually to acknowledge that this is an ongoing, and in many ways, a worsening emergency. We have to acknowledge that before we can really get to what's a mid-term and long-term sustainable approach," Evan Dreyer, Hancock's deputy chief of staff told us. "That, I believe, is gonna require greater partnerships with the region, with nonprofits, with the faith community."

Source: Denver's Joint Information Center

While he said the city didn't "choose" this responsibility, Dreyer added city governments like Denver have "a moral obligation" to care for people who need help. Whether or not they find a more cost-effective way to do that, he expects Denver will continue to field large numbers of people arriving from border cities for months.

The system strain goes beyond finances.

On New Year's Eve morning, two city workers sat in Union Station's underground transit terminal and waited as a bus arrived from Texas. They found their way to a handful of people who looked lost as they stepped off the Greyhound, spoke to them in Spanish and helped them head towards a processing center downtown. People show up at all hours, one of the workers said, and not just from the obvious buses pulling in from El Paso.

The worker, who didn't share her name because she wasn't authorized to speak to press, said she and her colleagues have been posted there for weeks. She usually does some other job for the city, but for now, this was her mandate. A few days ago, the city revised its municipal code to make sure employees diverted to shelters and efforts related to the migrant response are paid their usual salaries.

One man, who stayed in a rec-center shelter and was catching an eastbound bus to stay with friends, told us word has spread that Denver is a safe place to go. Migrants like him who arrived in El Paso have set their sights north.

Officials are hoping the city will be paid back for some of its spending on its emergency shelters. Denver received $1.5 million from the state. Hancock and Gov. Polis also set up a fund with the Rose Community Foundation to help cities in the metro better meet the need. Margaret Danuser, Denver's chief financial officer, said the city will also try to get some reimbursement from the federal government.

But backpay won't replace the hours city workers have poured into this effort, diverted from whatever else a local government should be doing.

Amy Beck, an advocate who helps people experiencing homelessness navigate Denver's regular shelter system, told us she's had a hard time connecting people with services since this all began.

While she and her colleagues praised the city's response to the pre-Christmas freeze, setting up more emergency shelters in the Coliseum and the Webb Building for people who are unhoused, there's growing recognition that the work to care for migrants has chipped away at Denver's ability to address other things. Dreyer said city employees are absolutely feeling the extra hours.

"People have been working every day - every day - for a month straight, through the holidays, to stand up these facilities to make sure that newly arrived migrants have food, that they have winter clothing, that we're able to transport people," he told us. "It's an incredible effort."

Denver needs a lot of help to make this sustainable.

In December, Denver Community Church (DCC) opened up its own shelter to help the city house migrants. But Dave Neuhausel, DCC's pastor of mobilization, said it had to shut it down before Christmas.

"We had tons of volunteers, and our coordinators around the clock were people we trained for this work. They've done and unbelievable job, but all these people have families and holiday obligations and full-time jobs," he said. "We did our eight-day effort, what we could do, then at some point we have to say, 'This is our limit.' We bought the city a lot of time during a critical timeframe when things were uncertain, and we've just seen an increasing number of arrivals."

Neuhausel added his church and its volunteers are eager to reopen their shelter, at least for the next six months or so, but they'd like the city to step in and help run things. Ideally, Dreyer said, Denver will lean more heavily on groups like DCC, and "all options would be on the table" in terms of how those relationships are managed.

Neuhausel said he's in regular conversation with officials on how and when to reopen. Meanwhile, Mayor Hancock appealed to Denver's Catholic Archdiocese and neighboring cities for help. Right now, Denver is shouldering most of this work by itself.

Both Dreyer and Cyndi Karvaski, who is working as a spokesperson for Denver's emergency Joint Operations Center, told us there are currently no large shelters being run by outside churches or nonprofits. They had to set up an overflow shelter in a city building downtown to keep people from staying outside or in the regular homeless shelter system. On top of moving city workers to help with the effort, the city has also opened 100 new positions to assist with the migrant arrival response and has begun making a new sign-up portal for volunteers to make it easier for people to help out.

Transportation is another big need, and Dreyer told us the federal government needs to step in with a national approach to help migrants move between cities as they head to unite with friends and family, find a place to stay, work and attempt to declare asylum.

He's grateful for the assistance nonprofits and faith communities have offered up so far, he added, and he's hoping they'll keep stepping up as this continues.

Stephanie Rivera contributed to this report.