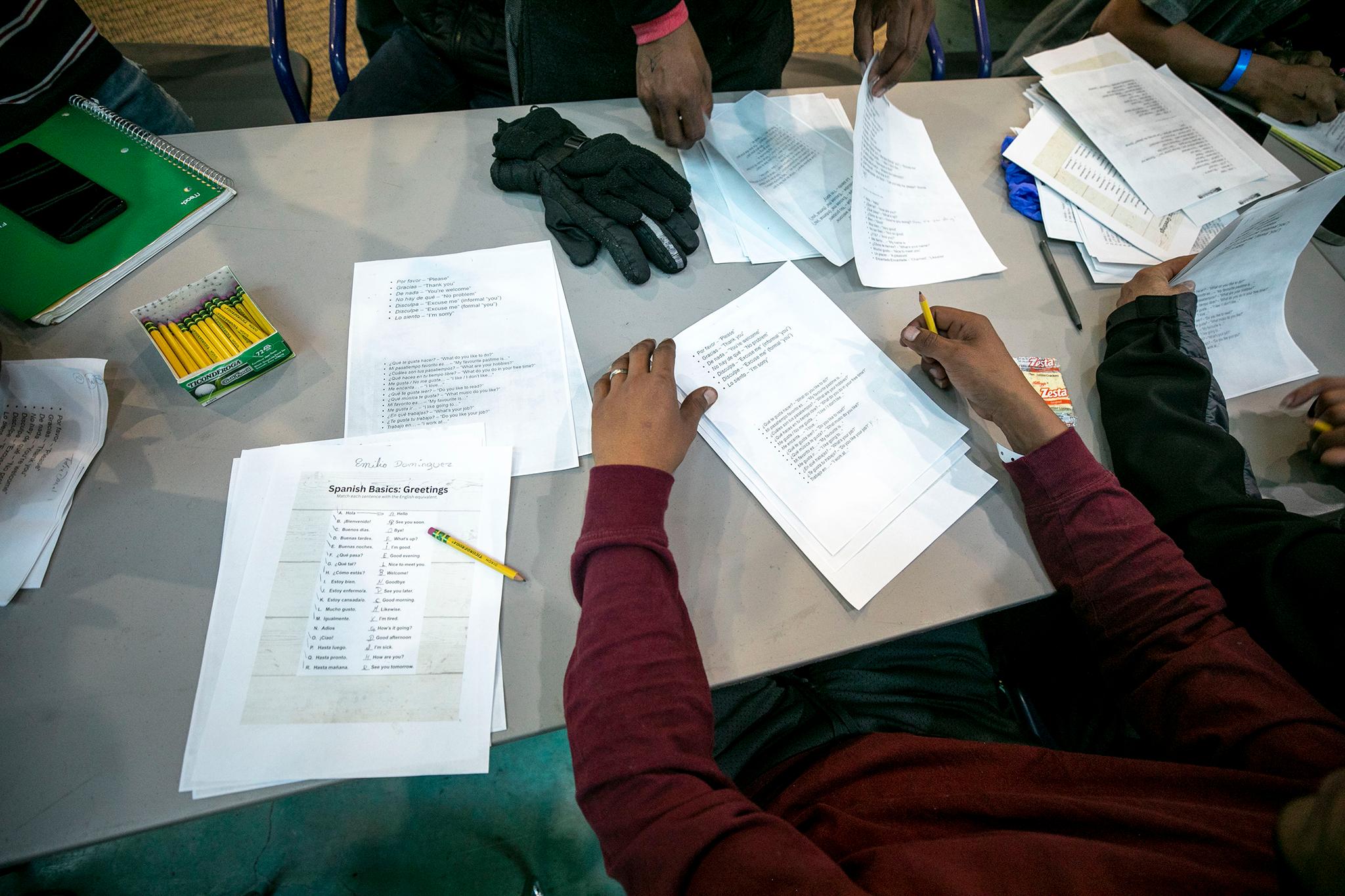

It's another busy day inside a west Denver rec center, where regular exercise has been suspended and a few hundred people have taken up residence on gym floors. A city employee, who would normally be doing some other job, stands over a table of men poring over worksheets.

"Trabajo es? Work," he says.

The men repeat it back to him: "Work! Work!"

While nonprofit and faith groups have been helping Denver shelter some 4,000 migrants who've arrived here from southern border towns since early December, the city has been doing most of this work by itself since the holidays. The effort has been made possible by city employees who've left their posts elsewhere to lend a hand.

Amelia Iraheta, who usually does emergency management for the Denver Department of Public Health and Environment, said her colleagues are really proud of the hours they've put into this project.

"Something like this really drives people towards a common mission, and I think it actually tends to be a very bonding experience for people," she told us. "It's really, really just making me feel more proud than I even normally do of where I work, because so many people are really committed to this work and they're continuing to do it."

Iraheta said guests heard about the shelter before they ever arrived in Denver. Their arrivals are testaments to her colleagues' commitment to the cause.

A lot of the people staying in this shelter are bound for other states. Some have family in places like California and Florida and plan to apply for asylum in order to attempt remaining here with them permanently. Others are just looking for a place to land, find work and eke out a life. Not everyone plans to stay.

Most made it to the U.S. after enduring extremely dangerous journeys through jungles and deserts. They've had to be resourceful, and they've built networks through message apps and online groups to get this far. Iraheta said guests have told her all about this; it's how a lot of people ended up in the city's care.

"They're organized amongst themselves, so we've seen a lot of people here who are telling us things like, 'I texted my cousin, or I'm part of a WhatsApp group that told me to come here,'" she told us. "I do think it speaks to the fact that the staff, that have been working tirelessly for the last month, are doing a really good job of providing the types of support that people are needing."

Most people staying in rec centers are single men and women. The city has placed families with children in motels, which have been used as shelters since the pandemic lockdowns of 2020.

Lately, Iraheta added, people have also arrived to reunite with people who've already left city shelters and found somewhere in the metro to stay.

"Of course, people are gonna congregate where there's already a community that they're comfortable with," she said.

Lisa Gibbs, who stepped away from child support services to manage the westside shelter, said she met a handful of men there who left, found jobs and got a place together. It was a moment of pride, she said, because the welcome she helped roll out for them translated to real stability.

"My heart's 100% in this," she said. "It's worth it."

Destination or not, other forces are reshaping Denver's role in this national issue.

While the 12-hour shifts, early mornings and late nights are points of pride for workers, they're also reasons why the city needs to transition this project into a new phase. For weeks, officials have been talking to leaders in churches and nonprofits to find a new home for its shelter program, which they expect will need to stay open for months. They want to re-open rec centers for regular business and get staffers back to their usual jobs.

Evan Dryer, Mayor Michael Hancock's deputy chief of staff, told us there's still no concrete plan for a move like this. A future configuration could lean on the Denver Catholic Archdiocese's Mullen House in west Denver, though an Archdiocese spokesperson said on Tuesday that they've not reached any deal. Dreyer said the shelter program could continue in city buildings that are less public-facing, or even cycle through other rec centers.

In the meantime, two things relieved pressure on Denver's existing emergency shelters.

First, Gov. Jared Polis' office chartered buses over the span of four days last week to take people where they wanted to go, mostly New York, Chicago and Florida, according to a city worker who helped get people on those routes.

State officials won't say how many people they transported, but Polis' office said the assistance was meant to alleviate a backlog of trips out of town that built up after winter storms and air travel delays halted transportation in the region. That ended after New York City Mayor Eric Adams and Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot sent him a letter "respectfully demanding" he stop. Denver is still helping people get on commercial buses, when they ask for assistance.

Also, President Joe Biden announced last week that he was doubling down on policies to bar people from crossing into the U.S. outside a port of entry, and made rules that will allow up to 30,000 from Cuba, Haiti, Nicaragua and Venezuela enter the U.S. each month and work legally for up to two years. To qualify, applicants must have a financial sponsor in the U.S. and pass a background check.

A nonprofit leader based in El Paso told us it's too soon to tell if that's had a meaningful impact on arrivals.

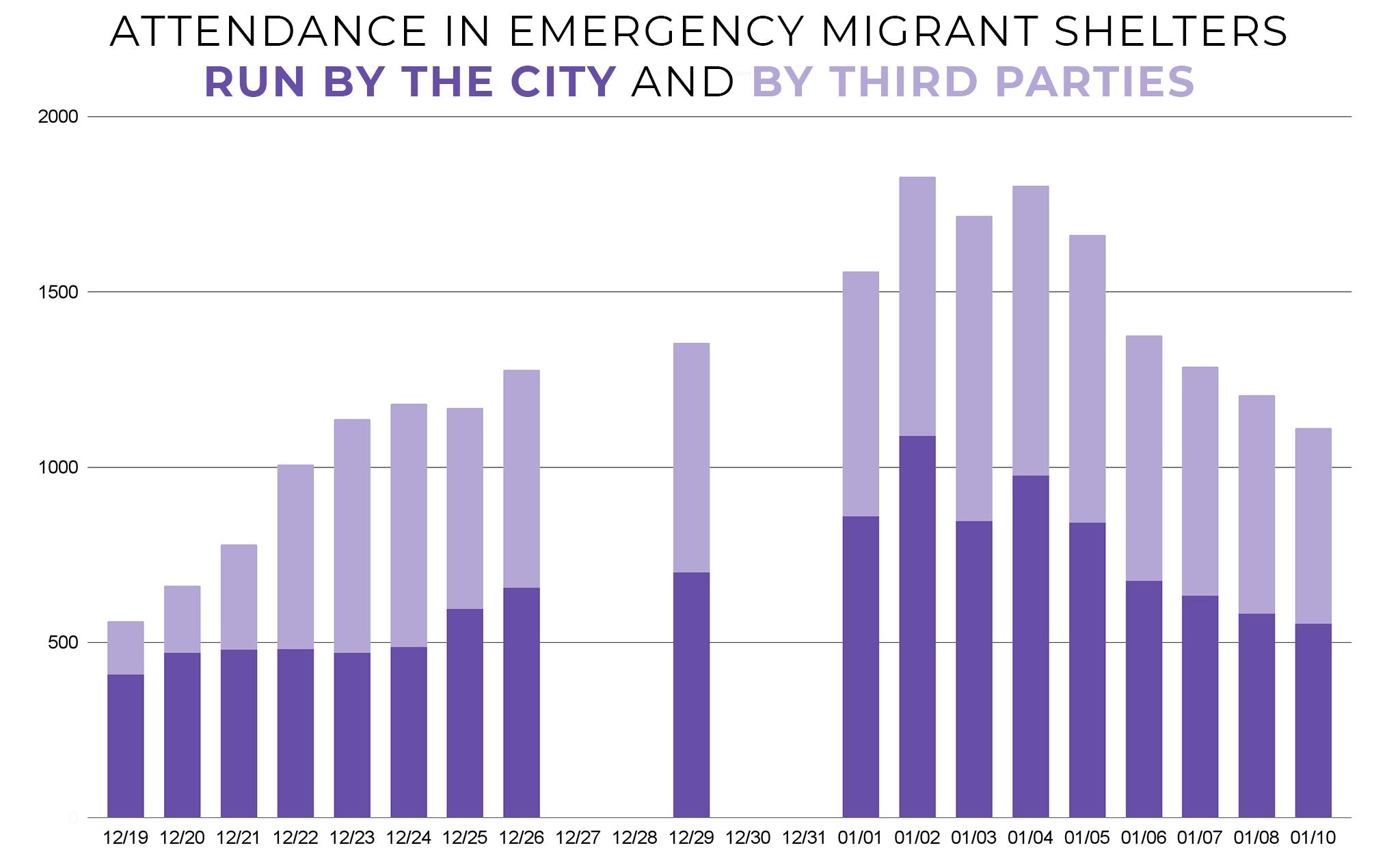

One way or another, the city shelters have housed fewer people over the last week, though numbers are still higher than they were a month ago.

Denver employees will keep doing this work for now. They believe it's the right thing to do.

Gibbs, the shelter manager, said she'll keep this up as long as she's needed. If the need lasted forever, she said, she'd love to switch between her day job and shelters.

"Honestly, every day I'm excited to come here. I was needing a little change in my day-to-day routine at work," she said. "For most, especially us human service workers, this is where our heart lies. So it was easy for us to just come over and start lending the hand into the community."

She and her colleagues come from all different sectors of city work, from public works to human services. Jill Lis, a Denver spokesperson, said this is how emergency operations are supposed to go: each person pulled into something like this has their own skill set, and they're trained how to use that background in new ways when needed.

Denver's Emergency Operations Center activated for COVID, the protests in 2020 and the Avalanche's Stanley Cup parade, she added, so they've had a lot of practice lately. She expects they'd be ready for anything at this point.

"The more that you practice, the better you get, and the more that we're used to how we can all work together collaboratively and get things done," Lis said. "Everybody is assigned to a specific position in the EOC, and so they just really do their job perfectly, and it fits like a puzzle and with everybody else."

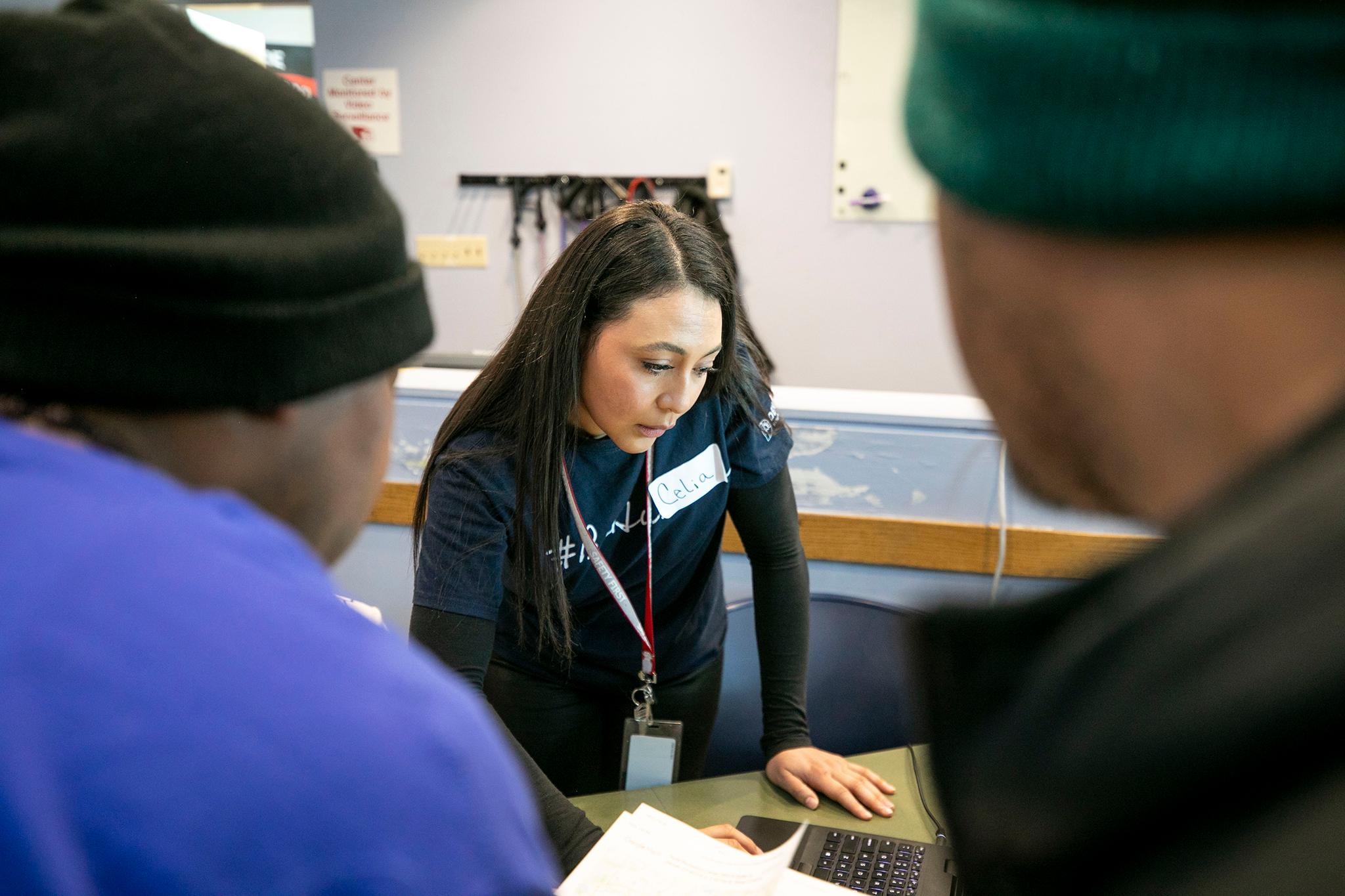

Celia Leal, who set aside her normal job with Denver Human Services to help sheltered migrants get on buses, said her contribution to this emergency response aligns with what city work should be.

"Growing up, my vision was to be able to get any step stones to help people, especially in the Spanish community," she said. "I grew up really close here, so this is my community. I'm more than happy to be here assisting."

It's a feeling shared by people who don't work for the city, who've stepped up in other ways. Denver's Jewish community has been handling donations, leaning on their faith as they support "the stranger." Marcel McClinton, who was handling food preparation at a short-lived shelter run by Denver Community Church, said he's motivated to show people a different side of America.

"There is something happening in the country right now, and in our communities, right now where we have dehumanized unhoused people generally, but we have made migrants the enemy," he said. "What we've been doing at the shelter is providing a welcoming, kind and comfortable environment as possible as we can, for folks who have seen and heard the absolute worst from Americans."

And it's personal for Iraheta of DDPHE. Her family fled civil war in El Salvador to come to the U.S. She sees them in the people she now works with in the transformed rec centers.

"There are a lot of similarities," she said. "This kind of work has meant a lot to me."