Last week, Denverites across the internet started tweeting about a politically charged postcard that hit their mailboxes.

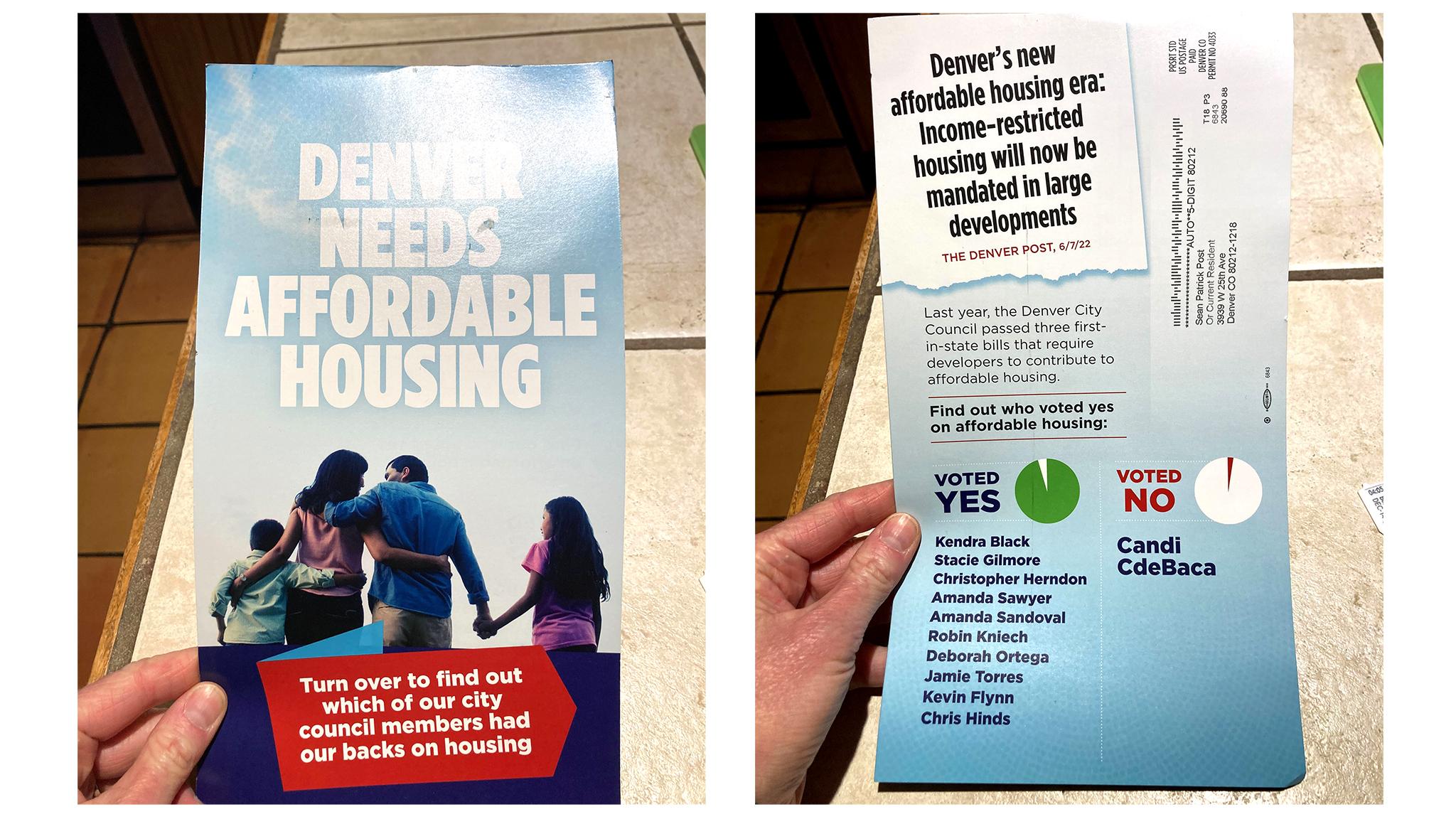

"Turn over to find out which of our city council members had our backs on housing," it read on the front. On the back were two columns: "voted yes" and "voted no." Only one council member was listed under the red-colored word "no," Candi CdeBaca. There was was no disclosure as to who paid for or sent the ad.

"Isn't it illegal for campaign mailers not to disclose who they're from/who paid for them? I got this gross, deceptive ad," Roshan Bliss posted.

CdeBaca chimed in that it was a "developer flex" to "mislead" voters, and characterized it as against the law.

But election experts say that probably isn't the case, based on the content of the mailer and its timing.

Here's why this is probably not illegal:

Mario Nicolais, a lawyer who's worked on election and campaign finance policy across the political spectrum for 15 years (and also writes a column for the Colorado Sun), told us there's two types of ordinances that govern this kind of messaging in cities, states and at the federal level.

The first is a concept called "expressed advocacy," which was established by a 1976 Supreme Court case and refined by more rulings by the high court. Basically, there are a list of words like "vote for" or "elect" or "oppose," direct calls to action, that turn a political mailer into active advocacy for (or against) a candidate. In Denver, he said, any type of communication that qualifies as direct advocacy requires a disclaimer that says who paid for it. Since the mailer does not include this explicit language, it probably doesn't need a disclaimer.

The second is a concept called "electioneering communication," which is defined as any communication that "unambiguously refers to any candidate, ballot issue or ballot question" and is released 60 days before a general municipal election or 30 days before a special or vacancy election. All electioneering communications require disclosures; spending on both expressed advocacy and electioneering communications need to be reported to Denver Elections if the bills exceed $1,000.

Because this mailer came out before that 60-day window, Nicolas said, it's not defined as electioneering communication and therefore not illegal under that ordinance.

"If they had sent this mailer on Feb. 4th, they would have broken the law," he said. "I think that this likely skirted right around the campaign finance laws in Denver."

Elena Nuñez is director of state operations for Colorado Common Cause, which advocates for transparency and access in elections. She told us she agrees the mailer probably doesn't run afoul of city election laws, though she said it defies the spirit of those ordinances.

"Denver voters have the right to know who's trying to influence their vote," she told us. "It feels like something where knowing who's behind it would be better for the people of Denver."

Both Nuñez and Nicolais said they aren't working with anyone involved in the mailer's creation.

Still, Denver Elections say they're investigating.

Lucille Wenegieme, a strategic advisor for the office, said the office got an official complaint Monday, which kicked off an official process to deal with the claim. She didn't add whether the city considered the mailer fair game.

CdeBaca said she issued that complaint and that she's been investigating on her own, tracing a postal permit code to an Englewood direct-mail company and then to a printer based in Kansas City. Getting to the bottom of it might help her politically, especially once independent expenditure committees start pouring money into our various municipal races.

But Nicolais said any legal battle over this piece of mail will probably go nowhere.

"You can always go to court in this country," he said, adding: "My guess is this will not get resolved before the election."