Denver is a weird place, fiscally speaking. While U.S. cities generally rely heavily on property taxes to pay for streets and sidewalks, we've gone in another direction.

Mayor Hancock's 2023 budget estimates the city will bring in $2.8 billion in revenue this year, and 45% of that is expected to come from sales taxes, the largest slice of the pie. Some of this has to do with limits on property taxes that are written into our laws, but that large share is also thanks to voters who have continuously added fees to purchases over the last four years. Since 2018, we've approved measures to increase our sales taxes by about 30%.

To put this in perspective, if you bought a $2,000 jacuzzi from the Home Depot on Santa Fe Drive in 2018, you'd have forked over $73 more dollars to the city. Today, your contribution to city coffers would be $96.

Source: Denver's 2023 Budget

$20 more doesn't seem like a big difference, and that's kind of the point.

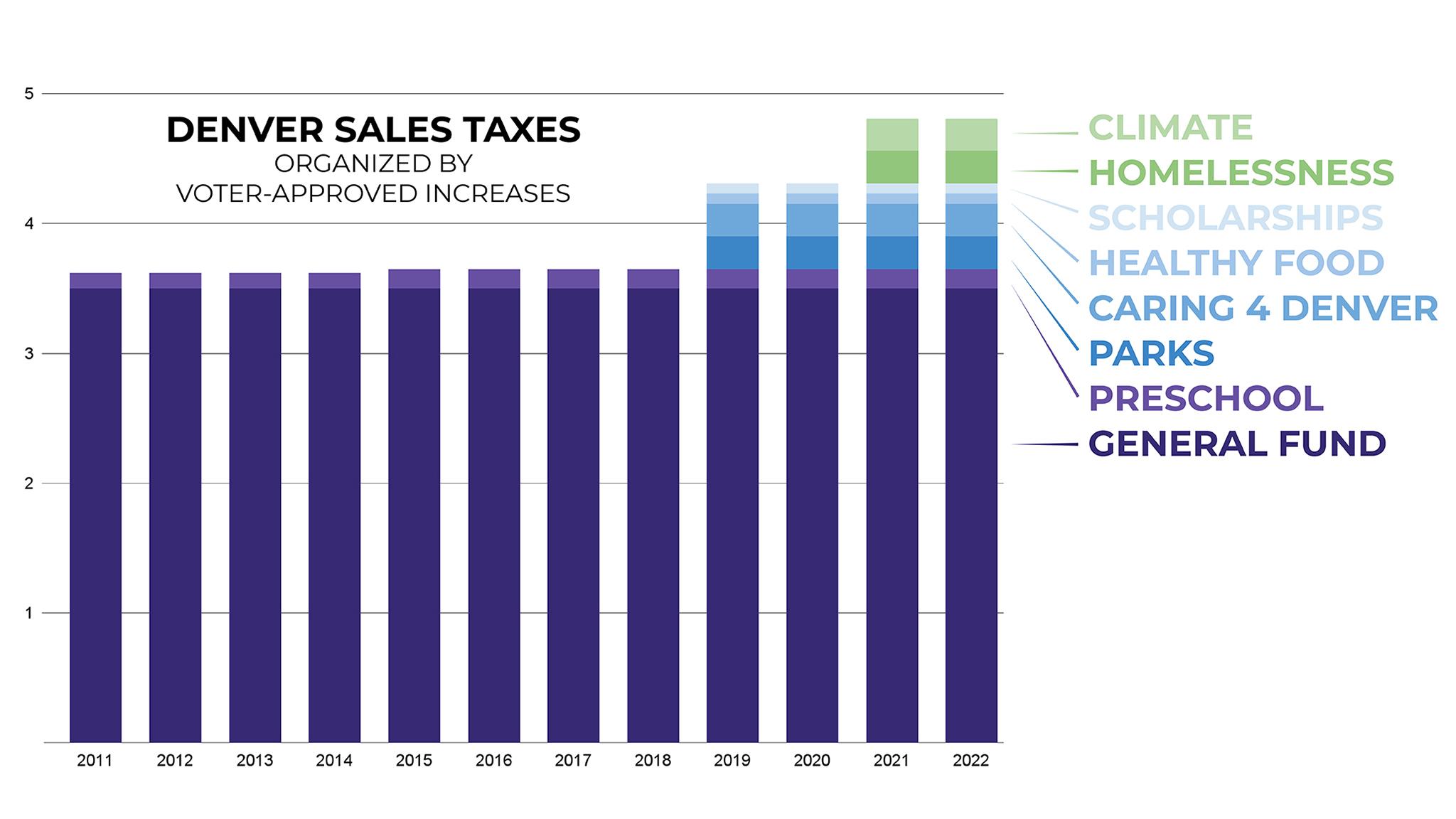

Denver's sales tax rate sat at about 3.6% for much of the last decade. Most of that was the city's baseline rate for its general fund, plus about a tenth of a percent extra for a preschool fund that was approved in 2006 and extended in 2014. In 2018, we decided to add .66% more to purchases to fund mental health services, healthy food for kids, parks and college scholarships. In 2020, we added an additional half percent to mitigate the city's climate impacts and fund solutions for homelessness.

Carrie Makarewicz, an associate professor of urban planning at the University of Colorado, Denver, said these self-imposed taxes can be seen as a list of residents' priorities. They're almost a projection of what we, collectively, want Denver to be. Then again, she added we've got a reputation for green-lighting almost anything on a ballot.

"The joke is Denver residents have never met a bond they didn't approve," she said.

Her colleague, public finance professor Christine Martell, said we've probably been so open to new increases because they feel gradual and generally far away.

"There's a dissociation between where you're spending your money and where you're getting your value," she said. "You're spending it on bread but you're getting clean air."

We should note that you're actually not spending it on bread, at least at a grocery store. Denver's sales taxes are exempt from most grocery items.

Residents are more likely balk at a property tax bill, Makarewicz said, since they're paid in one lump sum.

"A sales tax, it's harder for them to do a direct calculation in their head," she said.

There are drawbacks to this way of doing things.

The big one is something we've become very familiar with: Sales taxes can be volatile. Remember when everyone stopped buying things when the pandemic started? That had a huge impact on Denver's spending power.

COVID may be an extreme case, but Makarewicz said it demonstrates how external forces can mess with the business of running a city. Inflation is the latest force to rock the boat.

Property taxes tend to provide a more reliable cashflow, Makarewicz said, adding that they also put less burden on residents who may have a harder time paying for things.

Martell said we've also made things harder by raising taxes for every specific purposes. Most of the increases we've passed recently are permanent. The longstanding preschool tax expires in 2026; the scholarship and healthy food measures expire in 2030, unless they're renewed.

"What it does is it ties the city's hands, in some ways, in the long term," she told us. "Let's say, 20 years from now we have a different model of the world and we have different demands on the budget, then the city is still collecting old taxes."

Alyson Gawlikowski, a property tax expert who works for the city, told us Denver's tax configuration is related to TABOR, the 1992 measure that forced governments in Colorado to cap revenues that grew faster than inflation and development. In 2012, Denver passed its own measure to rid itself of TABOR, but replaced the state law's cap with its own.

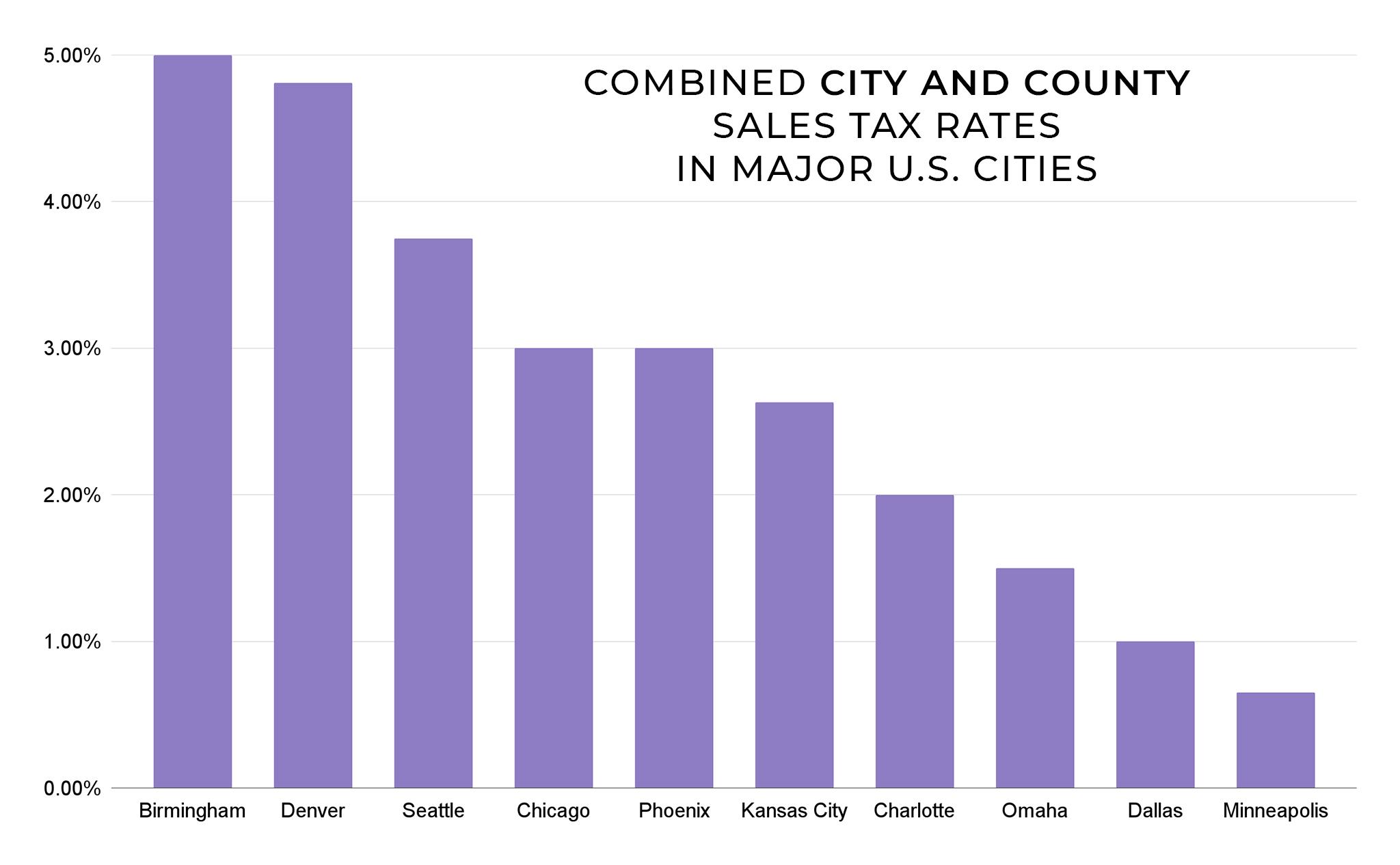

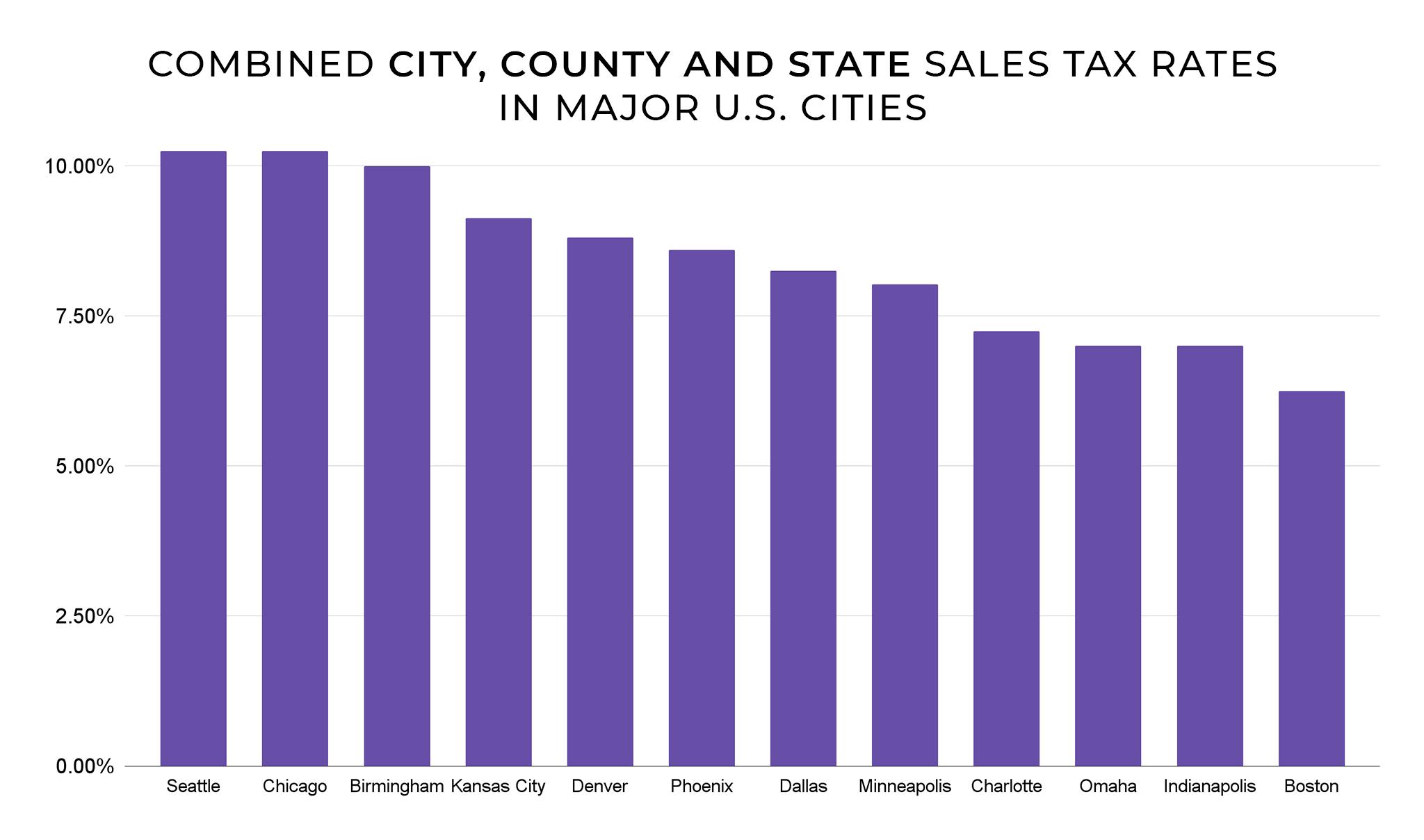

As a result, Makarewicz said, property taxes in Denver and Colorado are among the lowest in the nation. Our local sales taxes are pretty high compared to other large U.S. cities, but that's balanced out by low rates imposed by the state.

Correction: Carrie Makarewicz's title has been update to reflect that she is an associate professor.