Alejandro de Luna, a sinewy 34-year-old, never imagined being a firefighter when he was a kid.

For the past three years, he sat crunching numbers for a general contractor wishing he could do something more to help people.

He thought back to 2013, when his mother had a heart attack. He was out of the country, and firefighters were the ones who responded. He appreciated what they did for his family, and he wanted to serve others in the same way.

Tired of his office job, he decided to apply to the Denver Fire Department -- the largest in Colorado.

For several months, he's been going through the Denver Fire training academy, learning the basics of first aid, how to fight fires in burning buildings and cars, how to rescue people trapped in wrecked vehicles, how to brave a burning basement and find bodies in the dark, and how to care for someone having an overdose.

He's practiced these skills one by one. But when he joins the department, each 24-hour shift could involve several at once, along with other challenges he can't prepare for.

In their professional lives, he and his fellow recruits will put out flames, reverse overdoses, witness suicides and murders, and attempt to save dying children. They'll be a lifeline for shut-ins and answer calls for tummy aches, explosions and mass casualties, too.

Tonight, on the first Saturday in October, he and the other recruits of Class 2303 will put all of their skills to the test at Hell Night, a longstanding tradition aspiring Denver firefighters must survive before joining the department. It's the hardest thing they'll go through in their training -- a rite of passage, an affirmation of all they've learned and how much they've grown.

Before the fires start, the recruits share one of their last suppers at the training academy at 5440 Roslyn Street.

Soon, they'll graduate and join fire stations across the city, only seeing each other on emergency calls. Hell Night is a test, but it's also a celebration and a goodbye.

Half of Class 2303, as they're known, wrapped up in the afternoon. The other half, including de Luna, is about to start. A few sooty students, aching from the afternoon's drills, kick gasoline-rainbow puddles from leaking fire hoses as they head over to eat with the nighttime class, then pack up and go.

They meet a trio of fresh-faced recruits who just arrived, sitting on a curb and chatting about the challenges of the night ahead.

The new arrivals inspect their weary peers who survived.

They wonder: How bad will Hell Night be?

The fires begin as the sun starts dropping.

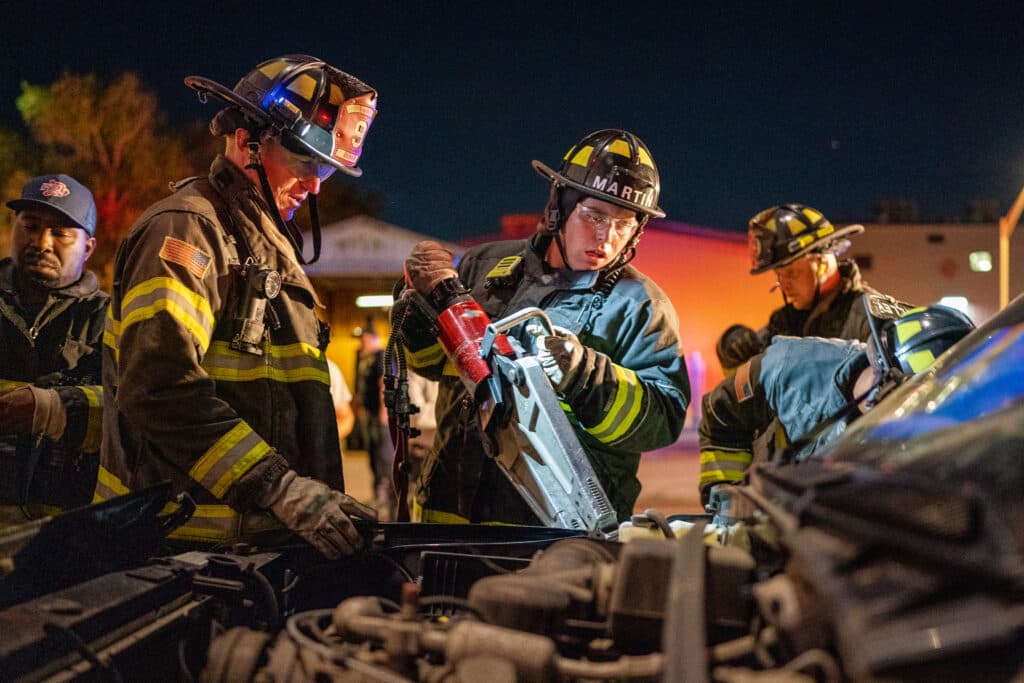

Hot flames rise from car batteries. Pistons explode and airbags pop like gunshots. Smoke billows out of windows in a building nearby. Voices cut through static, mumbling about medical emergencies. Crumpled vehicles trap stuffed mannequins inside.

On this cold October night, the recruits breathe in the burning wood, plastic and gasoline, sucking down tanks of oxygen. They heft fire hoses, run into blinding smoke, feel their way through burning buildings, drag limp, singed mannequins to safety.

The students are running drills on every emergency the department predicts they could face.

The top floors of a mock house catch fire. Fire trucks rush to the scene.

Firefighter recruits crowbar through prop doors made of iron.

Several hoist on their oxygen tanks, don their masks and charge inside.

Others climb ladders to the top of the building and saw through the roof to let out blasts of smoke.

Inside the building, the students search for mannequin victims. They find most of them. One they don't find.

A group searches a floor that isn't on fire, while above them, the building burns.

Eventually, they spray out the fire.

Officers stand by, arms crossed, and watch.

The recruits huddle up with their officers to discuss how it went.

The incident commander asks: What went wrong and what went right?

You searched a floor that had no fire while another burned. You left a victim behind.

You crow-barred your way in and put out the fire. You did your job with precision.

Good work. Do better. Here's how.

When you speak into the radio, press the mic toward your larynx and speak clearly in your normal voice. No need to yell. No need for inflection. Don't clog the channels with needless chatter. Officers need to be able to hear everything going on to coordinate a response.

Find a victim? Tell the supervisor. And if possible, do it face to face. With 50 radios, it's easy to create too much noise. Cut the blather.

Keep up the good work. It's a long night ahead. Fill up your oxygen tanks and head back to base. More calls will be coming soon.

De Luna, the 34-year-old recruit, takes a break from the flames.

"I think the adrenaline is just rushing right now," he says. "I mean, it's scenarios that we're gonna be able to put into the streets here in a few weeks. I'll be able to actually do this in the community. So I'm super pumped about it. I'm really thrilled about being able to start doing that and start making an impact."

He knows the job will come with trauma. He plans to meditate when things get tough.

"Whenever I feel stressed, whenever I feel like a lot of stuff is piling on me, I just go do that and go spend time with my daughter, with my fiance and kind of decompress."

Watching firefighters set up a simulation of a basement fire, Public Information Officer Captain J.D. Chism and Chief Warren Mitchell are reminded of the things that training can't address.

"Smell," Mitchell says.

"What's gonna be on your gloves when you pull someone out," responds Chism. "We can tell them that's going to happen. But skin coming off in your hands?"

The smell of suicide: "It just has such a distinctive sweet smell that your brain goes to every time," Warren says.

"It was never sweet," Chism disagrees. "For whatever reason, the way I smelled it, it was never sweet."

For Chism, smell works like songs. He can be living his daily life, breathe in and be transported back to a scene.

"It sometimes triggers bad memories," Mitchell agrees.

"It's that ammonia....it's that battery," Chism recalls. "Just talking about it, three or four situations just popped into my head."

"It's an ugly thing," Mitchell says.

Before he moved to a desk assignment, Chism spent most of his career working from firehouses on Denver's Westside and Downtown.

Driving through those parts of the city these days, he notices divots in the concrete where crashes he responded to took place. He sees the ghosts of flashing lights and mangled cars at empty intersections. He drives past vacant lots and remembers when they weren't empty. He eyes memorials put up by families for kids he couldn't save.

"It kind of just soaks in your brain," he says. "It just leaves that imprint."

Some of that trauma, untreated, has led first responders to abuse booze and drugs, to kill themselves. Other traumas manifest themselves in little ways that affect not just firefighters but their families.

"Why do we have to cut the grapes?" Chism remembers his kids asking him when they were smaller. His wife, too, couldn't figure out why it mattered.

The answer, for Chism, was simple: "My first dead kid was a four-year-old who was choking on a grape."

In another incident, he was treating a mom who had been shot, and while he and the crew were administering first aid, a cop got shot a hundred yards away. The team rushed to care for both the cop and the mother.

A month later, Chism showed up to another shooting scene.

"I start shivering like it's the middle of winter," he remembers. But the temperature was around 60, and he was wearing a coat. He shouldn't have been that cold.

After getting back to the station, he told his crew that he thought his reaction was related to the previous shooting. He needed to talk it through, and he wanted to model how to do so.

For decades firefighter culture discouraged mental health treatment, but over the past decade that's been changing.

"We can't take away the traumas that we're going to experience," Chism says. "That's part of what we signed up for. But we can recognize the signs. We can recognize something's a little off here. How do we get this person what they need?"

Sometimes that's firefighters debriefing together. Other times, it's seeking professional help.

Mitchell, who runs the training program, has been with the Denver Fire Department for nearly three decades and remembers when things were much different.

When he got his start, superiors yelled at the recruits. A few years back, corporeal punishment was more in fashion.

If a recruit messed up, he -- and back then recruits were virtually always men -- would be forced to climb dozens of stairs, loaded with gear. Now, exercise isn't used as punishment.

"It's a paramilitary culture that has been male-dominated for years and years," Mitchell says. "There's a lot of value to some of those paramilitary customs. We have to be able to make decisions in emergencies where orders are followed quickly."

But there is also value in asking questions. Firefighters should be taught good risk management. Training needs to incorporate both respect for the chain of command and critical thinking.

"You don't necessarily need to be running on a Montessori school's culture. But we're also not teaching people for complete compliance," Mitchell says. "We don't want them to run into dangerous situations without question. We want them to be able to say, 'Hey, wait a minute, did you see this?'"

Changing customs in training to encourage more questioning has been tough for some of the older brass. But like in most professions, older firefighters grumping about changes in how the job is done is also something of a tradition.

"That's a forever-ending human experience, where the old guys are gonna judge the young guys," Mitchell says.

It's not just the culture of firefighting that's changed over the decades. So have the demands of the job and the sorts of emergencies the new recruits will face.

There's the city's ever-increasing density. New buildings are designed around a new fire code. Sprinklers and fire-resistant materials keep things safer.

But there are new hazards, too. One breath of smoke from synthetic furniture can kill. Controlling fire in lithium batteries in multi-cell electric cars takes much longer than dousing out a gas fire. The city's increase in homelessness means more tent fires from people trying to stay warm at night. There's a drug epidemic on the sidewalks, and the firefighters know many users by name, having saved them with Naloxone multiple days in a row.

"There was a big shift when we had cell phones," Mitchell says. "We had a tremendous amount of call load increasing."

Chism estimates the call load has doubled and outpaced growth in the department. The more calls, the less sleep firefighters get in their 24-hour shifts.

Despite the demands of the job, Denver Fire has had a relatively easy time recruiting and retaining staff compared to the police and sheriff departments.

In kindergarten, Mitchell's daughter Saba told her teacher she wanted to be a firefighter like her dad.

She loved getting to climb into fire trucks. And holidays looked different for her family: They spent Christmas and Thanksgiving together at the fire station.

There were times she missed her father during his long hours. When her dad would come home and nap, she'd ask, "Why are you sleeping in the middle of the day?"

Yet, by the time she was in college, she knew she wanted to be in public safety. She wasn't sure how, so she joined the cadet program at Metropolitan State University.

She took various assignments with the Denver police, sheriff and fire departments. She knew she wanted to join either the police or fire department, and after coming out for a training event, she decided to follow in her dad's footsteps.

A month after graduating from Metro, Saba started the fire academy.

"It's been really awesome," she says, now 23 years old. "It was exactly kind of what I expected it to be. And it was a lot of hard work. But I went home every night and I was just happy. Like to be here, I was happy to be tired and just go back out and do it again."

On her seventh week of training, Saba's time at the fire academy was cut short after a bail-out exercise from the second story of a building. She climbed in and out of the window more than half a dozen times, and on the last one, her feet missed the window, and she landed on her back.

She broke two ribs, had a concussion and suffered from back and nerve pain on the left side of her body.

While she completed whatever work she could in the next few weeks, her injuries kept her from running drills. In week 10, she was officially deferred to the next class.

"The injury didn't make me want to stop being a firefighter or feel like this wasn't for me," she says. "I was actually more motivated, and I want to become better." Now, she says she's healed and ready to be in the academy's next class.

She's proud of her fellow recruits putting out blazes, even as she's also itching to be out there with them.

"We've been training on this, but now actually seeing them as basically professional firefighters, everything's coming together," she says.

As Hell Night comes to an end, the commanders light up one last vehicle, a white pickup truck spray painted with the words "Call Me an Ambulance."

It's a little joke for the recruits, who, like Saba, suffered their share of injuries, mostly twisted ankles and hurt backs.

As the inferno blazes, the recruits stand around the truck and watch it burn. The flames warm the recruits.

It's an explosive campfire, at once comforting and a vision of emergencies to come.

Above the recruits' heads, a firehose spews water toward the truck, reaching toward the flames.

Hell Night ends, and soon, the real work begins.