Denver Mayor Mike Johnston broke the news to city workers Thursday morning: The city is facing a $50 million deficit in 2025 and will have a $200 million deficit in 2026.

The city’s general fund spending will need to be slashed by more than 12 percent — more than during the pandemic, when it was cut nearly 10 percent.

The mayor told employees at an all-city meeting they would face furloughs this year and that a restructuring of the city would be announced in late summer or early fall, as the budgeting process begins.

Everything, including layoffs, the reduction or elimination of programs and the consolidation of departments, is on the table in 2026, he said. The city will undergo a massive restructuring with an emphasis of making government “smaller, faster and easier.”

Hiring freezes start today. Furloughs begin June 1.

The city will move more government services online, cut red tape and rightsize the budget, the mayor said.

The city is launching a public outreach campaign for feedback on how the city should cut the budget, identify what services matter and don’t, and how the city can speed up city services and make them cheaper.

Starting in 2025, the city will institute a tiered furlough system, with employees taking between two to seven unpaid days off. The city will enact a hiring freeze until Sept. 15. Departments will limit discretionary spending, and the city will reduce and restructure contracts.

Johnston still plans to spend big on homelessness and big projects

Since taking office, Johnston has spent mightily on both the homelessness and immigration crises. In 2023, the city spent $73 million on both. The following year, Denver spent $86.6 million and in the following year $76.2 million.

Johnston says he plans to continue spending on homelessness resolution as an investment in downtown and the city.

And despite slashing government, Johnston plans to invest in “catalytic projects.”

Big projects will generate revenue, the mayor says. Those big projects include downtown reinvestment, the expansion of the National Western Center, contributing to a stadium for the National Women’s Soccer League team and the debt package he hopes voters support in November.

These projects are not funded by the general fund but by a Capital Improvement Fund that can only be spent on infrastructure.

Elected officials and city workers alike have been in the dark about how bad things could get.

Even as Denver City Council met last week and tried to set priorities for the 2026 budget, they didn’t have budget projections from the mayor’s office.

Morale is already bad among city employees

Multiple city workers told Denverite that morale has already tanked. An untold number of employees will lose their jobs as the mayor and his executives decide how to restructure the city government. Unlike in previous administrations, Johnston is not offering them early retirement and has not determined what a severance package might look like.

Compared to 2018, the city’s budget rate of growth has already declined slightly. In 2020, during the pandemic, spending was cut by nearly 10 percent. Last year it rose by just 1 percent to $1.76 billion.

Agencies froze vacant positions in recent months. In April, the Department of Finance recommended that those unoccupied jobs disappear from agencies' rosters for the next few years altogether. Meanwhile, the mayor was trying to push through long-awaited raises for a dozen executives — some up to 44 percent, but that decision has been postponed.

The safety department has already slashed year-round mental health care for the police and sheriff departments’ employees. City leaders were asked to cut discretionary spending to balance the 2025 budget.

Heading into 2026, the cuts will go even deeper. The city will attempt to shore up core services and prioritize what residents actually need from the city: trash collection and public safety. But even those services will be strained.

How did Denver get here? Sales tax, Trump and the end of pandemic relief

The city has been spending more than it’s bringing in. In previous years when Denver has done so, there has been a cushion of savings. This year, the fund balance has dropped below 10 percent of the budget.

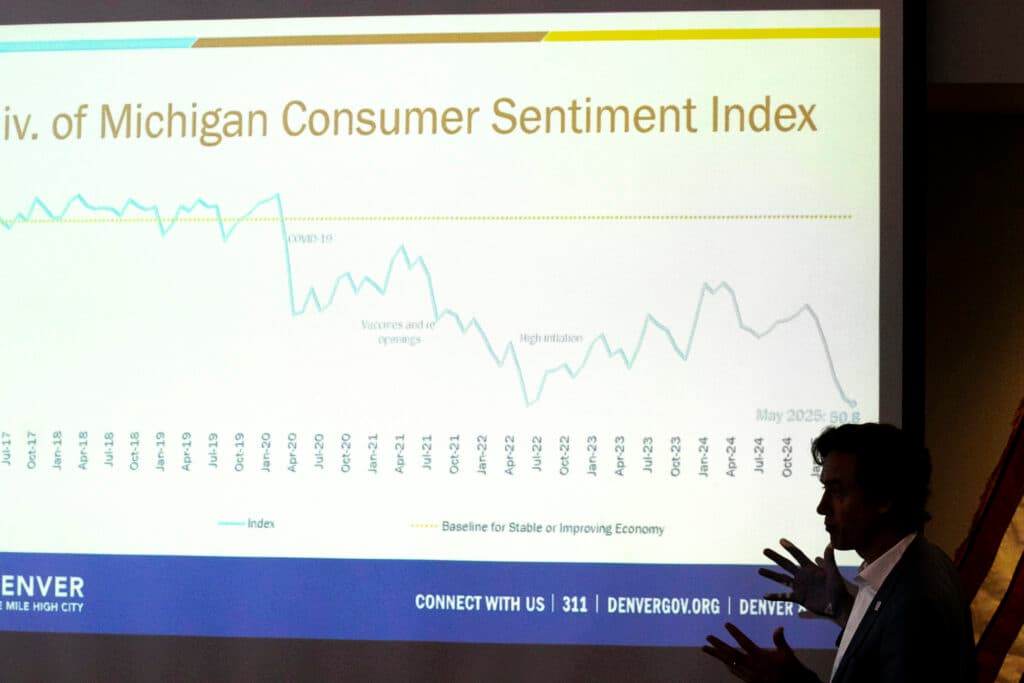

The growth of sales tax revenue, a major source of general fund financing, has slowed, as the cost of living has risen. People are buying fewer nice-to-have items. Trade wars, the ebb and flow of President Donald Trump’s tariffs and high interest rates all make for a turbulent economy that has people squirreling away their money.

Consumer confidence has dropped dramatically since January nationwide and in Colorado, Johnston said, pointing to the University of Michigan’s consumer sentiment study.

Major construction projects have snarled the city’s downtown economic engine in the Union Station, Central Business District and Capitol Hill neighborhoods. Business is down. Storefronts are empty.

The city was expecting 3 percent growth this year, but it has stalled out.

Those local issues have been compounded by Trump’s ongoing attempts and threats to cancel or claw back millions in federal funding, including $24 million already promised to the city, a move the city is fighting in court.

Trump has said he will deny money to projects that do not align with his values. Through a flurry of executive orders, he has pledged he will defund projects related to diversity, equity and inclusion as well as state and city protections for unauthorized immigrants.

Denver has defined itself as a welcoming city to new immigrants for decades, and the value of equity is baked into law — putting it at odds with federal policy under Trump.

Across the U.S., local government leaders have been meeting with their congressional delegations and the White House, demanding their communities get their share of federal funding.

Denver is also grappling with the end of federal pandemic relief. The city used federal pandemic relief funding to support social service programs without a long-term plan to fund them. Those programs helped slow the bleeding from the city’s housing crisis that started before the pandemic and escalated in 2022. But they did not solve it.

The American Rescue Plan Act money was for one-off projects — not long-term programs. But unlike many other cities, Denver didn’t treat it that way.

Denver courts have seen a record-high number of eviction cases, even as the city has scrambled to address rampant homelessness.

Like Denver, cities around the country are trying to understand how the Trump administration’s moves to limit the size of government will affect local economies – and many are uncertain, making it tough to budget for 2026.

These issues are not unique to Denver, said Irma Esparza Diggs, a director of federal advocacy for the National League of Cities.

“There is economic uncertainty,” Esparza Diggs said, and that is trickling down to states, cities and consumers.