By the first of August, about 20 people will have to leave SAFER, the well-respected Arapahoe County shelter that serves as an alternative to jail for people with mental health issues.

But even as soon-to-be laid-off caseworkers help them scramble for new shelter, housing and support, those same residents are trying to save the place they say has kept them alive and sober.

Residents said they were devastated to learn on July 1 that the program would end in just a few weeks — especially since it spent millions of public dollars buying the hotel shelter.

“It kind of broke me,” said Edward Rodriguez, who has lived at the SAFER shelter for nine months and watched many residents go on to find stable housing — something he hoped for soon.

SAFER was founded by a former public defender, Gina Shimeall. She wanted to stop people with mental health issues from cycling in and out of jails and prisons and instead help them create stability.

The shelter promised something residents say other shelters couldn’t: a safe place to put their lives back together with caring staff. The program has been embraced by the courts, the local sheriff’s office and nonprofits alike as a smart and successful alternative to jail.

Residents and advocates are begging the owner and operator, Mental Health Colorado, to keep it open until another entity can take over the program.

But trying to save the program is futile, according to Vincent Atchity, the CEO of Mental Health Colorado, the nonprofit that took over the program in recent years.

He, too, believes SAFER is a success — except for its funding. Mental Health Colorado cannot afford to maintain SAFER, he said.

Residents and community members are organizing.

Residents met on Monday with attorneys, a former state lawmaker, caseworkers, housing advocates, a former director of Mental Health Colorado and the founder of SAFER to brainstorm ways to keep the program open.

Atchity was invited but declined, and did not participate in a video stream. He’s on vacation.

The group discussed how to raise money, search for new host organizations and even whether they could sue to stop the closure.

SAFER founder Shimeall said she has filed a legal memo with Arapahoe County expressing concerns about the closure of the program. She has given the county a list of organizations that could take over the program.

She learned about the closure of the program she founded through the rumor mill, not directly from Mental Health Colorado.

When Shimeall handed SAFER over to Mental Health Colorado, the organization promised to run the program into the future, she said. Shimeall was never notified that the group was considering ending SAFER, and she was never asked to help find ways to save it.

“I find it ridiculous the time frames involved, that they did not call,” she said.

She blasted Mental Health Colorado for not reaching out to the organization’s partners, the sheriff’s office and the judges who collaborated with the program.

“It is appalling,” she said.

Andrew Romanoff, the former CEO of Mental Health Colorado and the current head of Disability Law Colorado attended the meeting. His organization is exploring representing the residents of the shelter in accessibility discrimination legal actions.

Resident Steve Bhattacharyya spoke at the meeting. He has spent his life in and out of jail and shelters. After his latest stint in prison, he went to a halfway house, but struggled to stay sober because the place was full of drugs.

SAFER was different.

“I've been able to maintain my sobriety the whole time here, because the staff are super supportive,” he said.

He’s reconnected with his mother and sister and found stability for the first time in his life.

But all that’s going away.

“My probation officer and I were under the impression that I was going to be here for months and be able to straighten out all my stuff, get months of sobriety and maybe be able to move on from that,” he said. “But it's been drastically cut short.”

Now, he’s organizing to save the program.

Despite the swell of public support, Atchity says there is no hope the program can be saved.

He said his organization didn’t have enough staff or time to ask individuals for money to save SAFER.

“We are a very small nonprofit organization,” Atchity said. “Our main work is advocacy. We took on this brief direct service role out of a mission-alignment sensibility and as a COVID response. And we just can't sustain it."

The organization spent about $2.8 million in 2023, according to its most recent publicly available tax forms. The organization held more than $9.2 million in total assets.

The hotel shelter costs $200,000 a month to operate. Other organizations bill Medicaid to fund similar programs, staff said. Mental Health Colorado does not.

Federal funding is too uncertain now to rely on, Atchity said.

Atchity said Mental Health Colorado needs to reprioritize its core goal: pushing government officials to adopt care-not-cuffs policies that prioritize treatment over incarceration. To do so, it needs to get out of the business of offering direct services.

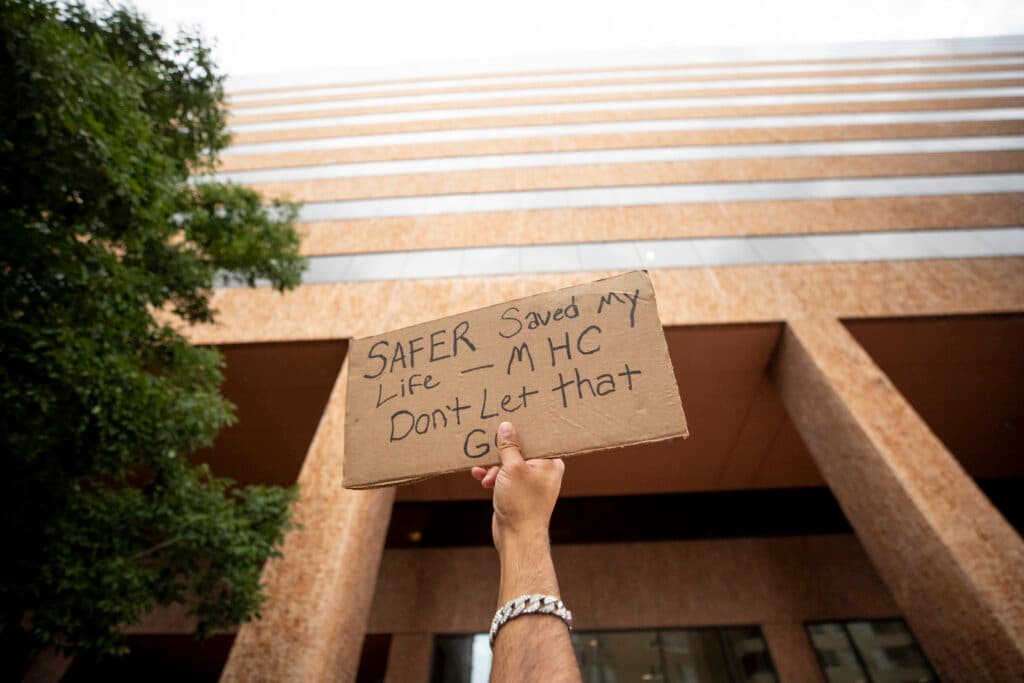

Residents protested Mental Health Colorado this week.

On Wednesday, a small group of residents and advocates came to Mental Health Colorado’s Capitol Hill headquarters to protest the closure and demand a meeting with Atchity.

Again, he refused.

“My view is that they think that they can apply some pressure, and somehow operational funds to continue this program are going to be squeezed out us,” Atchity told Denverite. “We’re not the government. We’re not the Apple corporation. We’re not Amazon. There is no ‘there’ there as far as squeezability. So I think it’s just putting fuel on a fire that needs to go out.”

Millions spent on building

Safer Housing, an LLC that shares an address with Mental Health Denver, bought the building in December for $4.8 million for the permanent operation of SAFER, according to Arapahoe County documents.

The purchase was funded with $2 million from American Rescue Plan Act funding distributed through Arapahoe County, along with money from the state and the Colorado Housing and Finance Authority.

Now, Mental Health Colorado plans to sell the property, though it has no offers on the table.

Residents say selling the building would be a poor use of taxpayer resources.

“I reached out to Congressman Jason Crow's office and asked him to open an investigation on this mismanagement of federal funds,” one resident said.

Atchity said there was no ill intent. His organization had “an unrealistic timeframe for putting together a business model that was going to sustain that work.”

He watched the clock run down on operating funds and realized “there was no way we were going to be able to stand up a sustainable business before those funds ran out.”

What happens with the money the public spent on the building?

Atchity says money from any sale of the property will be used to reimburse the groups that funded the purchase.

His organization will not sell the building for less than the organization spent. Arapahoe County attorneys are negotiating the details for getting the grant funds back, according to a county spokesperson.

Arapahoe County assesses the building's value at just over $3 million, though Atchity believes the land’s location likely has greater value.

Who will eat the cost if buyers refuse to offer the full $4.8 million?

“With that worst-case scenario, that building will just sit there empty and rot in place until someone comes along,” Atchity said.

What if Mental Health Colorado makes a profit on the sale? Would the nonprofit keep the earnings from money invested by the public?

“I'm not commenting on a speculation about a better real estate outcome than we're expecting,” he said.

What’s next for residents?

There are not enough housing vouchers for the roughly 20 residents living at the shelter. Caseworkers are trying to find new programs and housing options for them.

But residents are panicked. Many have disabilities, and they have received a shorter notice than a landlord would have to give them if they were renters.

They know it is unlikely every person will find a new place.

Caseworkers and advocates with the Housekeys Action Network Denver cautioned residents to fight for themselves and ensure they have somewhere to land, even as they fight to save the program.