Where does affordable housing come from? A question almost as pause-inducing as "where do babies come from?" But the answer is not, "I'll tell you when you're older." This time, we're going to get into it.

One way is the city's Inclusionary Housing Ordinance

Denver gets state and federal grants to finance affordable housing. But the city also has its own affordable housing fund, created in 2001 and funded by "developer contributions."

Those contributions come as a result of Denver's Inclusionary Housing Ordinance, which has been around since late 2001.

We'll talk more about the money part in a bit, but IHO also mandates some creation of affordable housing units.

At its simplest, it requires all newly constructed, for-sale housing development projects of 30 or more units to make 10 percent of the units affordable. You build a 100-unit apartment complex, 10 of the units should be set aside for people earning 95 percent of area median income or less, depending on what type of building is constructed.

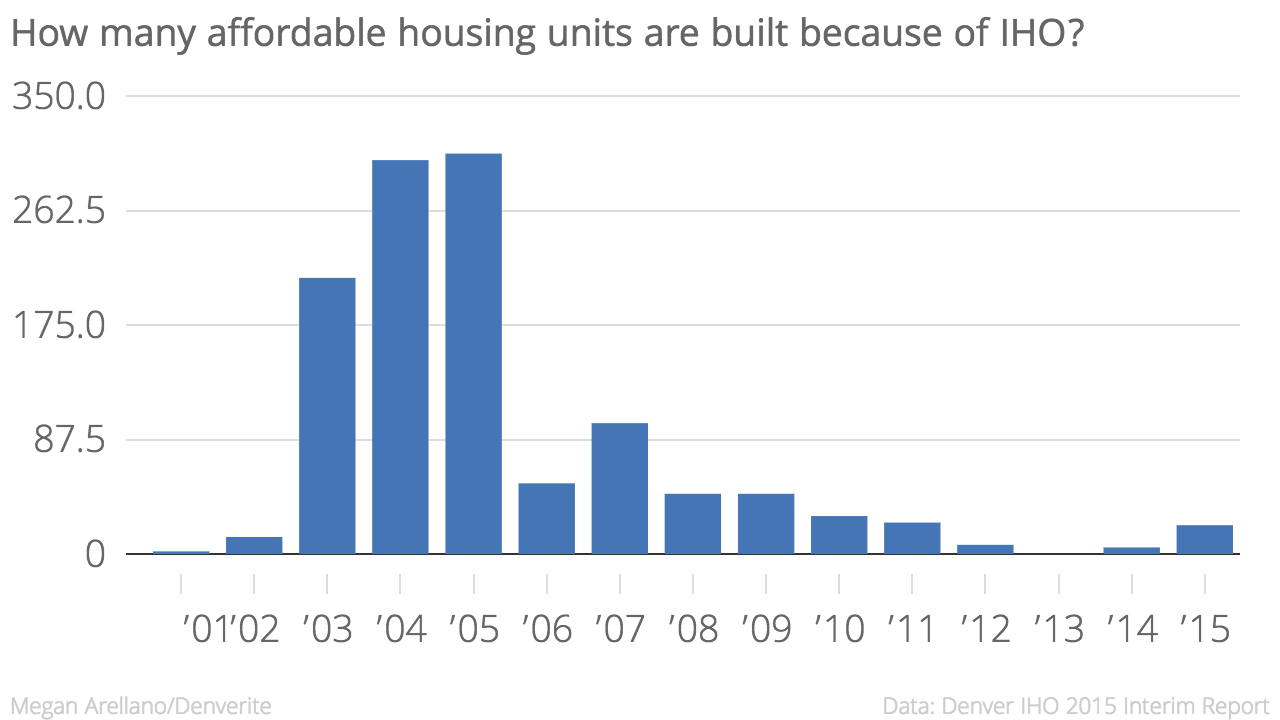

Over the past 15 years, 1,166 units have been built as a result of IHO, according to Denver's 2015 report. Most of those were in the early years of the ordinance.

Why so few?

Well, the report says "tighter lending standards and construction defects requirements" have kept the number low. A lot of people blame construction defects liability for drying up the condo market in Denver, and IHO only applies to for-sale units, not all the rental that has come on the market.

Others believe it incentivizes certain types of development. While I was reporting my housing flipping story, Councilman Rafael Espinoza told me that the IHO created an incentive to build 29-unit projects.

Also, developers can just pay money instead of building affordable units.

That seems like one hell of a loophole

It may sound like capitalism gone awry -- developers can just pay their way out of contributing to the affordable housing stock with the cash-in-lieu fee. But it's not that simple.

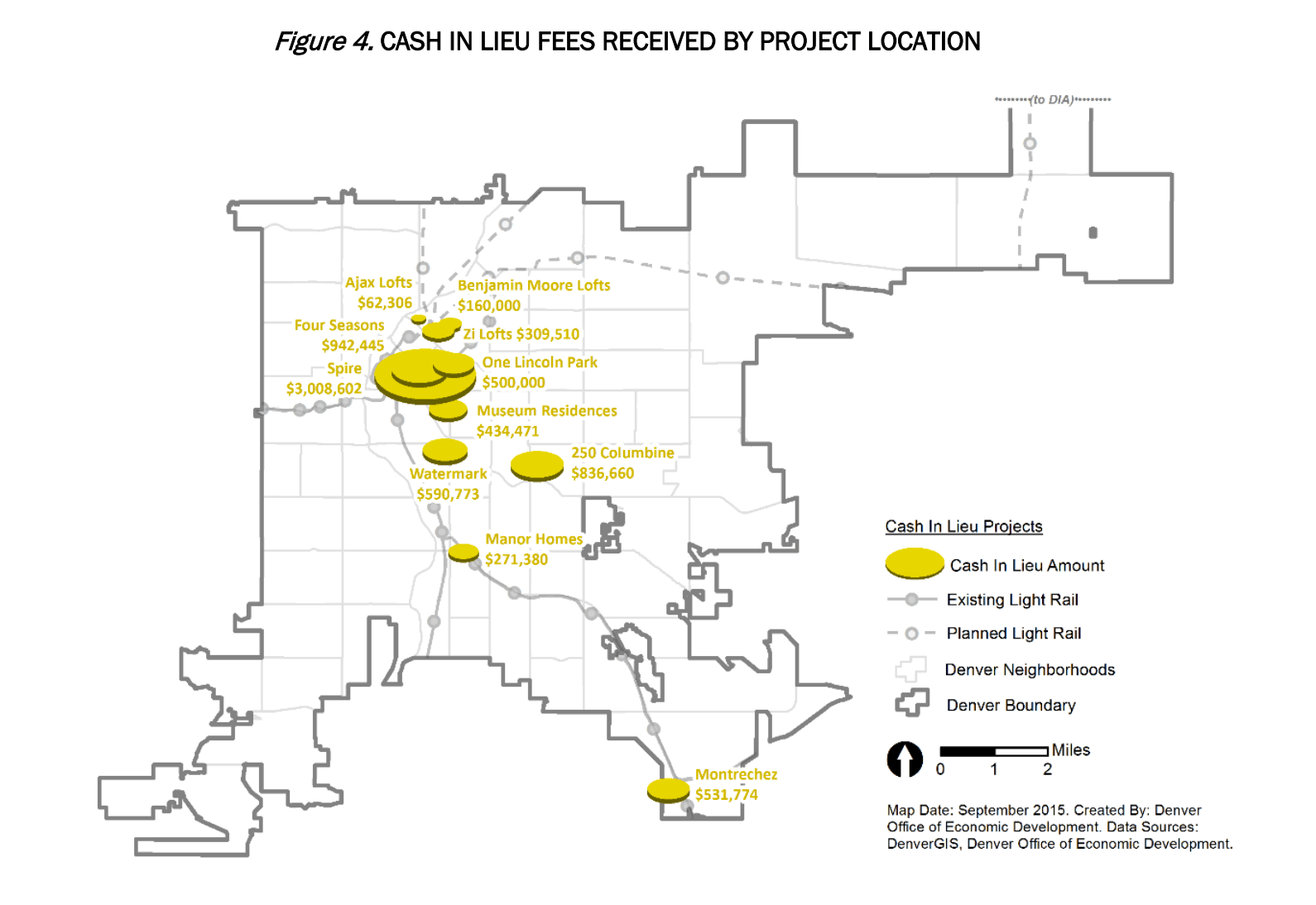

Denver had about $10 million in the IHO special revenue fund as of October 2015. About $7 million came from developers paying the cash-in-lieu fee.

Roughly a quarter of the $10 million has been paid out to other developers in the form of rebates and incentives for building affordable housing. Another 40 percent is still in the fund, awaiting the next use. And the money that isn't used for rebates can be reinvested by the city in other affordable housing projects.

Boulder Housing Coalition's Executive Director Lincoln Miller argued in the Daily Camera that cash-in-lieu actually builds more affordable housing for Boulder.

"Especially when housing is being built in smaller batches, by smaller developers, it's preferable for builders to pay into the affordable housing pot, and let the non-profit sector specialize in creating affordable housing."

In Denver, about $2.7 million has been reinvested for affordable housing projects. That money has created 479 affordable units for people earning 60 percent of area median income or less. That's about 2/5 of what the IHO itself has produced in its entire lifetime.

And a 2009 federal study of cash-in-lieu fees found that yes, the practice does help improve the existing housing stock. Though the study also notes that these fees mean that affordable housing isn't mixed in with market-rate housing but is segregated in completely affordable projects.

There's certainly a big difference between where cash-in-lieu fees were paid in Denver...

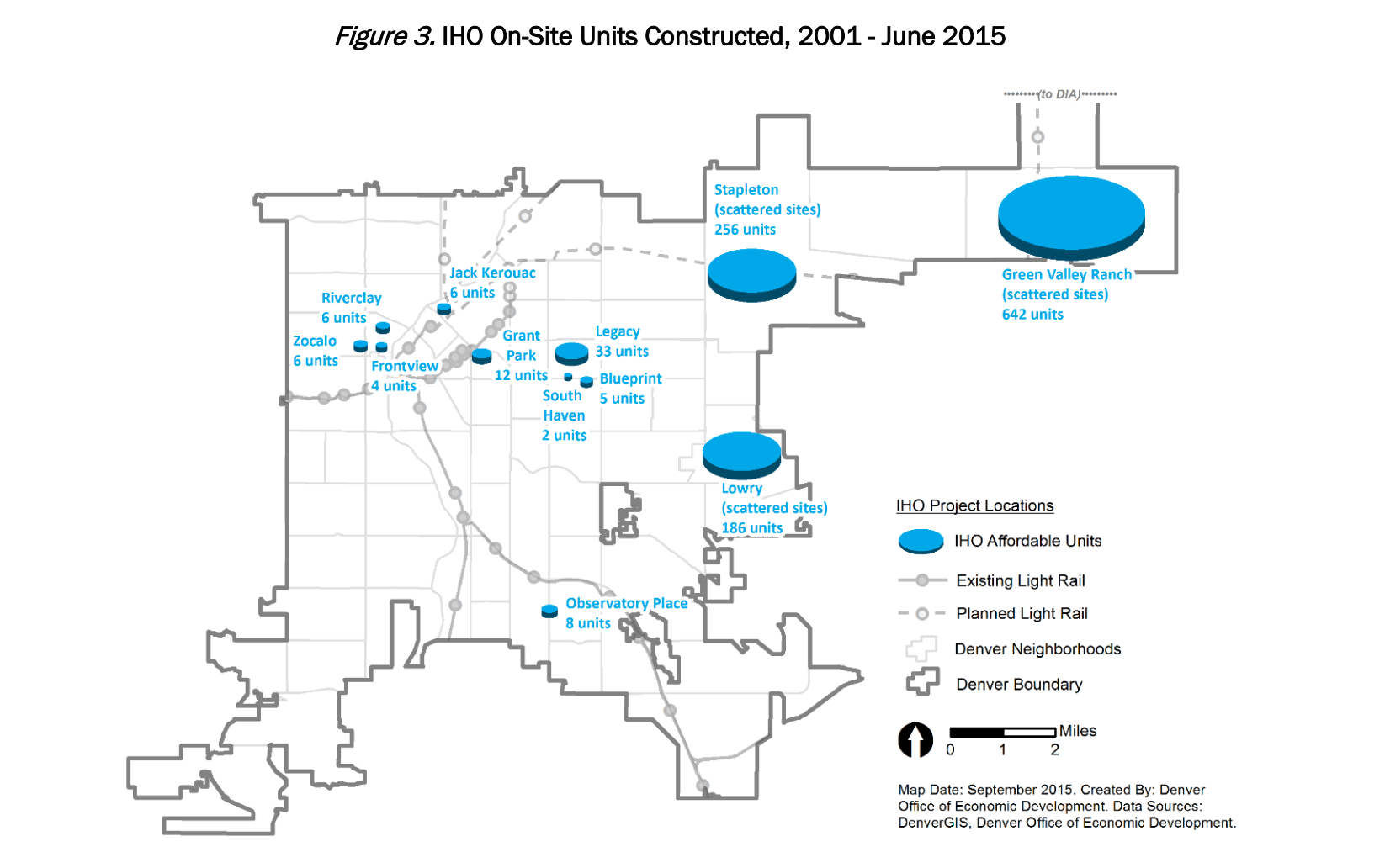

... versus where developers chose to build some affordable units.

Ok, I think I get it. Why is it going away?

There's a lot of pressure to do more to address affordable housing in Denver and, generally, the efficacy of IHOs is in doubt.

More to the point, Mayor Michael Hancock called Denver's IHO a failure in 2013. In order to emphasize/renew his commitment to affordable housing, Mayor Hancock is pivoting to a new $155 million fund.

But that doesn't mean the process will be a cakewalk. We've said it before, but I'll say it again: There is no silver bullet.