Twenty-thousand people walk some portion of the 16th Street Mall on a typical day. Imagine it without them -- no chiming buses, no rickety pianos, the endless light posts gone dark, the oaks and honey locusts uprooted.

You're left with a half-million square feet of empty space, more than a mile long. Now imagine someone handed you those blank blocks and told you to get to work.

"It was very unusual," said Henry Cobb, the 90-year-old architect who designed the Mall, in an interview with Denverite. "I don’t think there’s any precedent for the 16th Street Mall, actually."

The year was 1977, and Denver was ready to do something ambitious.

"The ascendancy of 16th Street as a center point went up through probably the mid-60s," said John Olson, director of preservation programs for Historic Denver.

Back then, it was "the ribbon of light and noise and energy that held it all together. It was our Broadway, our Sunset Boulevard, our Champs-Élysées," complete with "elegant, hulking movie palaces" and "sprawling department stores," as Patty Calhoun wrote for Westword.

By the '70s, the middle class was sprinting for the suburbs, taking stores and theaters with them. Nationwide, downtown retail sales had fallen 15 percent in about 20 years, according to urban designer Jessica Schmidt. By the '70s, downtown Denver's roads were somehow traffic-packed and desolate at the same time.

"During that time, they started getting a hold of consultants and really putting up the idea far and wide, about who could come up with an idea that could help this place out -- and they eventually got a hold of Pei and associates."

Remarkably, the Mall happened just as people were losing their taste for urban development.

For decades prior,"people were driving big expressways through the middle of cities, and wrecking downtown," Cobb said.

"As part of the resistance to all of that, there was a real revolution in planning, in which large-scale metropolitan planning essentially was thrown out, and planning in most cities was turned over to local community groups. It was all about bottom up."

Maybe it helped that people had been talking about the idea of the Mall for so long. In Denver, the idea had been circulating since at least as early as 1959, according to Olson.

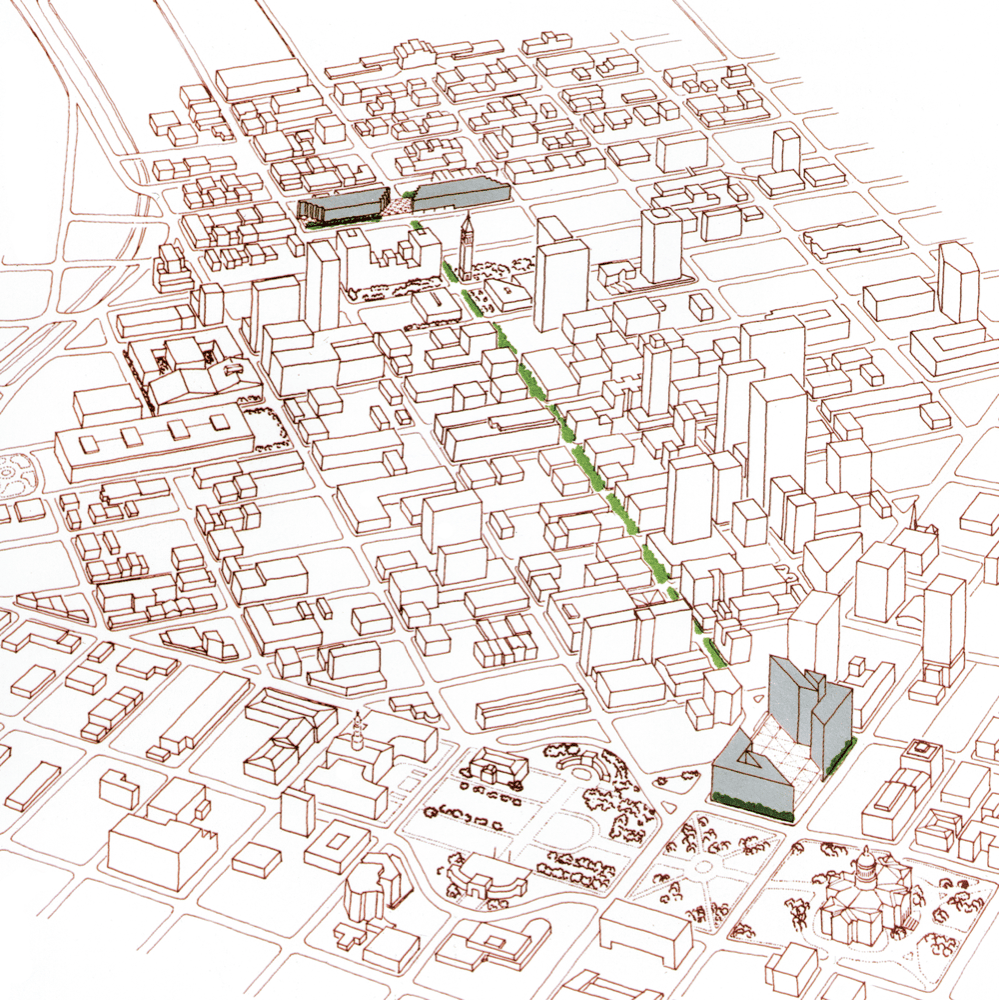

The plan was to connect two of the city's great modern structures, Skyline Park and Zeckendorf Plaza (a Pei design), both now demolished.

By the time 16th Street Mall finally started to happen, about 200 cities had created pedestrian malls.

Most of them would fail by the 1980s, but Denver made a choice that, for better or worse, has kept 16th Street Mall busy for more than 30 years: The city decided that the Mall wouldn't just be a place to walk -- it'd be the core of the city's new transit system.

"The whole idea of the Mall was to strengthen the downtown as a retail destination, and at the same time relieve the congestion of traffic," Cobb said.

He was 50 years old when his firm got the job, and he knew it was a rare opportunity.

"We didn’t build a building," the architect said. "It’s all about the public realm. It’s all about the street."

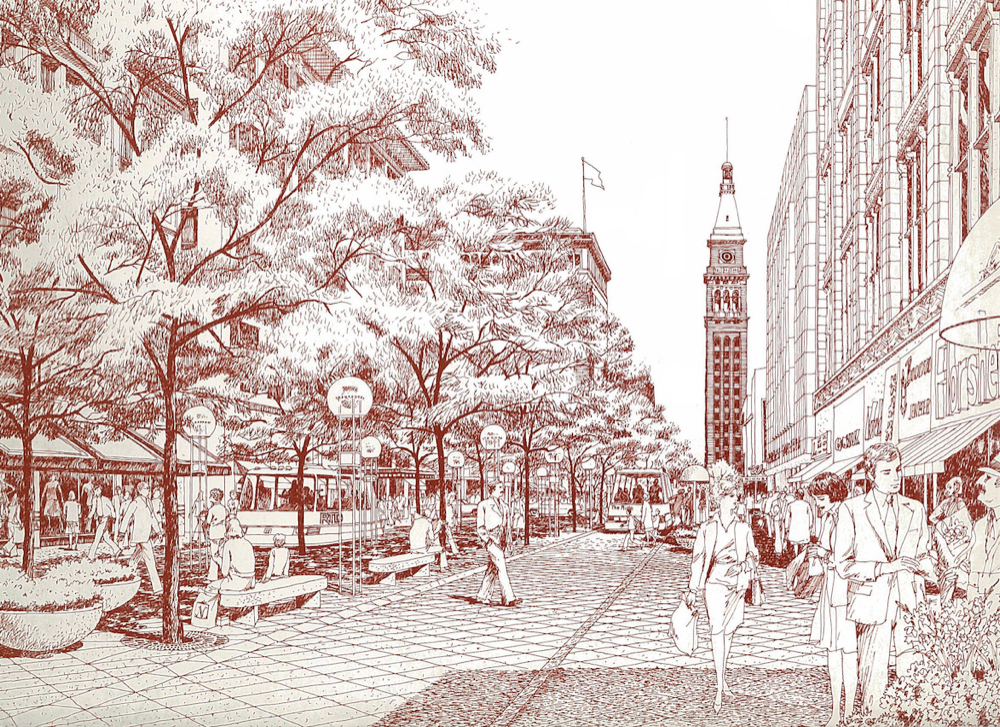

The architectural instinct at the time was moving to "a kind of Disney-fied fun-house design," he said. You know -- elaborate signs, fake rustic touches. Cobb wanted the opposite. He was raised on the clean lines of modern design.

"We were very much against loading this place up with a whole lot of stuff. We wanted it to be very simple," he said.

"So we widened the sidewalks, and we did not put trees in the sidewalks. We put trees in the middle," he said. "It was designed to be complementary to the shop fronts, but at the same time to give a strong landscape presence in the middle of the street."

He zeroed in on the details, meticulously plotting sight lines and figuring out how to keep those trees alive.

"You'll never see a system of curbs and drains more carefully detailed than the 16th Street Mall," he said.

And the city, Cobb said, went with nearly everything that he suggested -- except for the plan for futuristic "electric shuttle cars," which didn't really start to happen until last week.

In a way, Cobb thought differently than modern designers.

Today, Denver's planners talk constantly about "activation." The new goal for the 16th Street Mall is to make people linger, to give them stuff to do.

All through the last two summers, Denver has focused on making the strip fun. There have been giant ball games, oversized chairs, spinning contraptions and all manner of interesting stuff. They've been monitoring people on the mall, watching them with automated people counters, asking what they want to do.

Back in the '70s, they didn't really talk about the Mall as a thing that would be entertaining in and of itself. Cobb saw that he was creating a big slate that others would draw on later. Build it, and they will come.

"The plan by choice is a simple one. It is a framework and setting for both the present and the future," the plan reads.

"Filling it initially with an array of podia, playgrounds or other fixed objects would preempt opportunities for creating things later on."

It wasn't easy.

The project ultimately cost about $167 million in today's dollars, according to figures from the Denver Business Journal. Construction was a pain. J.C. Penney left for the suburbs right in the middle of it. And something like 200,000 people showed up when it finally re-opened.

Remember those 200 pedestrian malls we mentioned earlier? Barely a tenth of them still exist today. They just couldn't compete with suburban malls.

Schmidt, the urban planner, describes it like this:

"Suburban malls had more retail space, more parking and more customers, and retailers continued to relocate there. Many people viewed downtowns as unsafe and the new indoor malls had private security guards, instead of relying on an overburdened police force.

"The malls were built as a solution to solve a city’s problems and could not live up to such high expectations."

And yet 16th Street survived.

Now, I'm not saying you can't complain about the Mall, because people sure do. It's "too touristy." It's crammed with chain stores. Half of it shuts down at about 9 p.m. It's where the mayor is trying to stop a "scourge of hoodlums." Those beautiful pavers are having some problems.

But what you can't call it is empty. The original goal was to use transit to fill the middle of Denver with pedestrians. Cobb's design did that. The rest is a work in progress.

"If properly maintained, 16th Street is part of the solution, not part of the problem. I think it’s still a viable solution to an important urban planning problem," Cobb said.

"I just hope people don’t throw up their hands and say we want to give up the whole thing. It should be part of Denver's DNA now."