The City Park Golf Course, a modest course that cleverly folds 18 holes into a rather small space, has become the latest touchstone in a very contentious debate about flood control.

The golf course is meant to become a link in a $300 million chain of infrastructure projects that will protect the low-lying areas around the South Platte River. It would be the first and one of the most visible elements to start construction, with the final design to be established next year -- and the opposition is reaching a fever pitch as that date draws closer.

At a recent Cabinet in the Community, Mayor Michael Hancock faced shouted critiques of the planned redesign of the golf course, and he was presented with an actual scroll with some 2,700 signatures from an online petition to "save" the century-old course, which would be rebuilt and redesigned so that it can temporarily store floodwater during heavy storms. Earlier this fall, hundreds of people turned out to discuss the project at the course's clubhouse.

Meanwhile, a lawsuit to stop the project has a judge's permission to proceed.

This is a fight that started, arguably, in north Denver and has arrived now in the wealthier neighborhoods clustered around City Park. It is part of a complex, massive and interconnected array of projects that the city and the state have planned for the years to come. Taken together, they've drawn out perhaps the sharpest challenge of public opinion that Mayor Michael Hancock faces at present.

Question one: Is this a boondoggle?

Let's start with a little context. The neighborhoods south of the South Platte River have always flooded during large storms. Water runs through the streets, sometimes getting deep enough to swamp cars. The farther north you go, the deeper the water tends to get.

The reason is that the city and developers have over the decades blocked up the natural path that water wants to take out of Montclair Basin. With no creek or stream to follow, the water makes its own stream, usually through the streets. Montclair is the largest basin in Denver without a surface route for water to escape.

"Whatever creek was there kind of disappeared," said Jamie Price, the director for the city's Platte to Park Hill flood control project. "It’s hard to go out and solve a problem at a point when there’s not a system to connect to. We’re starting literally from square one."

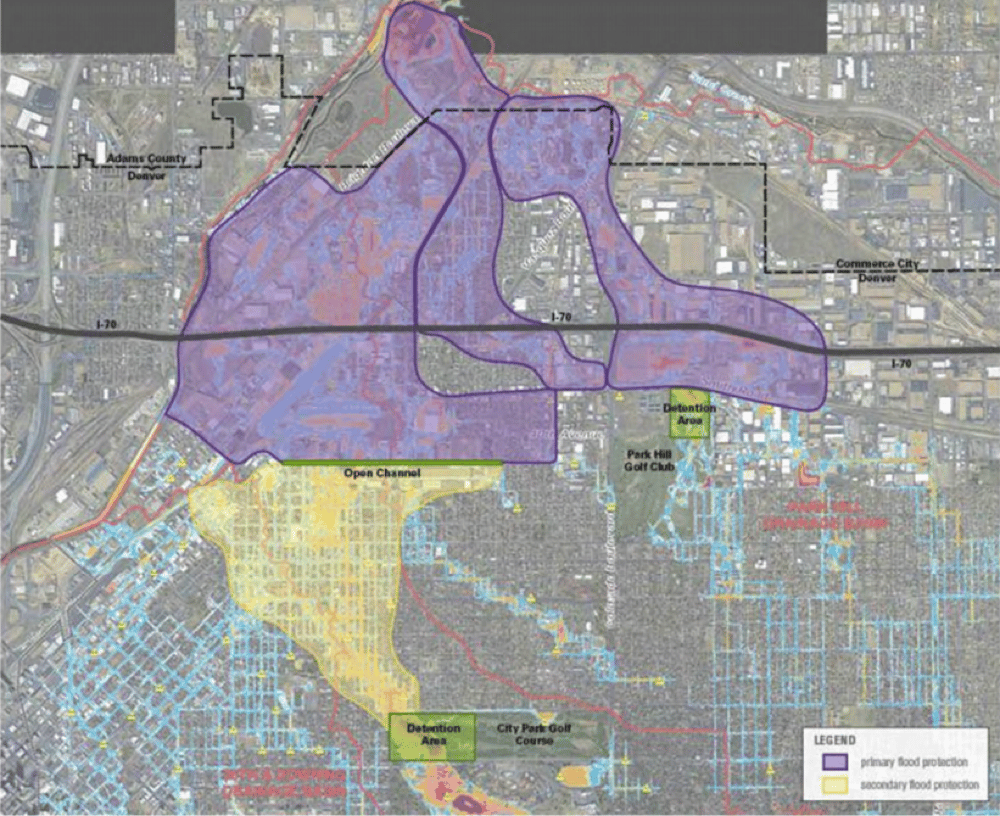

Platte to Park Hill involves turning the 39th Avenue corridor into an open channel (the city says this will be a recreational amenity for the neighborhood with natural plantings and a multi-use path, similar to Harvard Gulch) and redesigning City Park Golf Course to hold water during large storms. From the golf course, water would travel down toward 39th Avenue, where the channel would take it through a left turn toward the South Platte River, with an outfall at Globeville Landing.

But here's where the controversy starts to kick in: All this water-handling stuff is happening right as the city and the private sector embark on a much-debated series of projects across north Denver, including the expansion of Interstate 70, the rebuilding of the National Western Stock Show, the rebuilding of Brighton Boulevard and the general luxury apartment bonanza happening in RiNo.

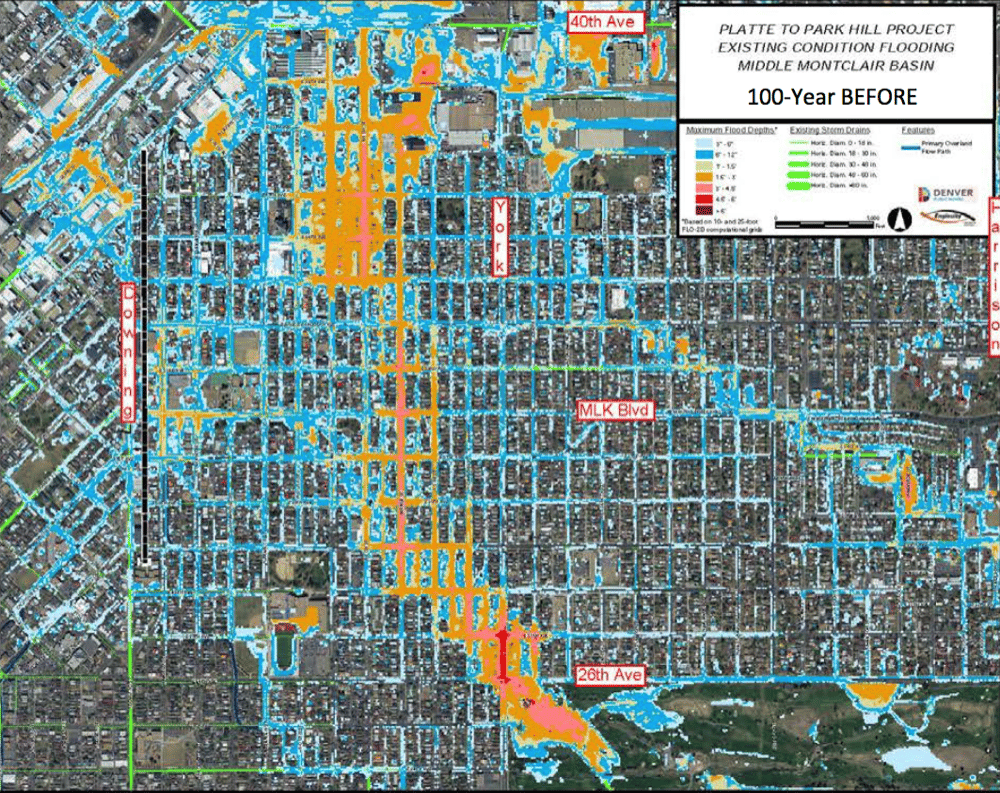

The area that will benefit the most from these flood controls is right where most of this stuff is happening. Here, check this out -- this is how a huge flood currently would play out, with no improvements, with orange representing deeper water, according to the city:

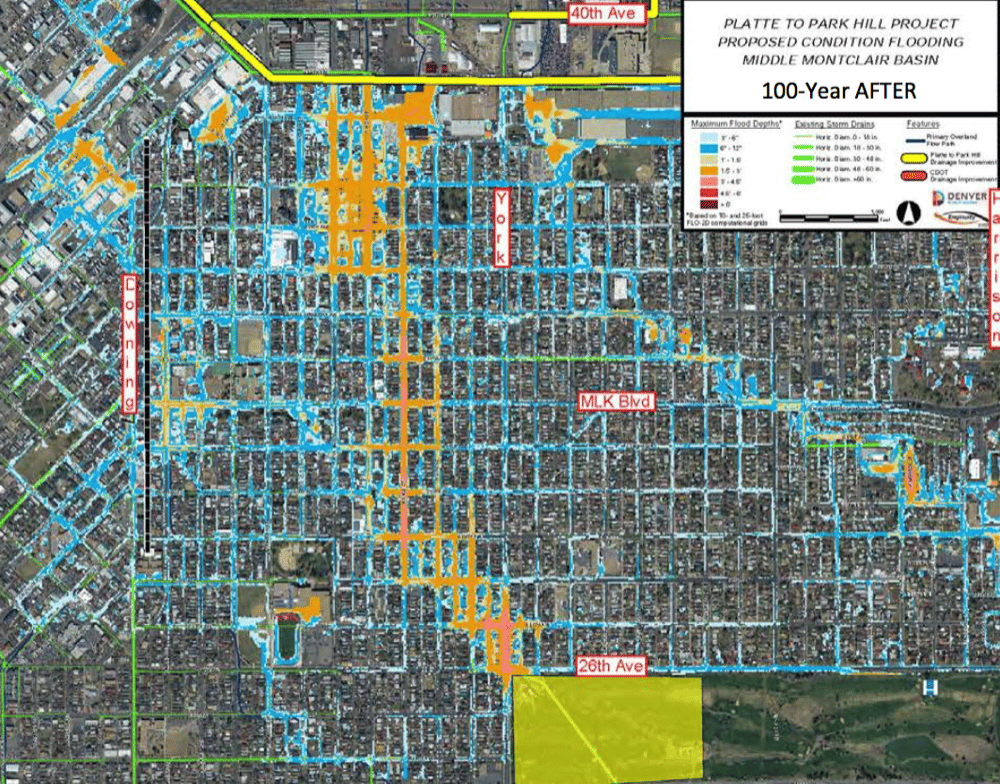

And here's how it might look if the Platte to Park Hill system is completed -- note that big yellow line at 39th Avenue and the total lack of water north of it:

So, comparing the two maps, you can see that the water is generally reduced in the orange areas -- but the real business is happening north of 38th Avenue, which suddenly is bone dry in a flood.

That area extends much farther north than the map above indicates. It includes the National Western (due for a $1.1 billion upgrade), Interstate 70 (where another costly renovation is planned), industrial areas near the river that could be prime for RiNo-style redevelopment, the residential neighborhood of Elyria-Swansea, and pretty much everything else between 38th Avenue and the South Platte River. (Here's a more detailed map of the area to be protected.)

The biggest reason this area of protection is controversial is that the I-7o rebuild is controversial. "The whole drainage thing is to protect I-70, which is a boondoggle," said Bridget Walsh, one of the most vocal critics of the city's flooding plan.

The state of Colorado's plan is to widen I-70 and sink it into a trench; neighborhood advocates in north Denver want to see the highway rerouted away from the residential neighborhoods that it tore in two when it was built several decades ago. (They're currently trying a couple ways to stop the highway plan.)

The "genesis of this had nothing to do with natural restoration of the buried stream in the Montclair Basin," wrote Christine O'Connor, also a critic of the project, in an email.

Platte to Park Hill definitely would benefit the highway rebuild, but the city and state contend that, for one, the city would be trying to control floods whether or not I-70 was happening, and two, that the state could take care of itself without the city's help. The two governments say the projects are an efficient way to simultaneously protect the I-70 rebuild and the basin around it.

Why does it matter? Because the construction of Platte to Park Hill would be a long process with a lot of impacts for east and north Denver, from the potential disturbance of toxic soil in former-industrial areas to the closure of a popular golf course for some two years.

Also, there's the usual water paradox: The upstream community is being asked to do something that would have the most benefit in downstream areas. The area around City Park doesn't flood particularly much. So, the city is stuck selling people on a project that won't change things for them, at least not initially.

The I-70 thing makes it triply more difficult, because the fight against the flood controls is by proxy a fight against the highway. For Brian Hyde, the question is whether the city should be doing this much to protect development of a flood-prone area.

"I'm a firm believer in acknowledging that the bottom land is the bottom land," said Hyde, a critic of the flood control program and a former state coordinator for the National Flood Insurance Program.

On top of that, the system faces skepticism for being too protective, at least of certain areas. It's being designed to handle a 100-year storm – one that has a 1 percent chance of occurring in a given year. That's the level of protection required for the interstate project, but the city says it's one worth pursuing regardless.

"They’re doing a very expensive drainage program, when we’re facing drought coming up here, pretty close," Walsh said in October. "They’re devising a system to get our precious rainwater out of Denver and into the river." (For what it's worth, the city is building reservoirs farther down the South Platte that can recapture water.)

Asked about the project's necessity, the city points to the flood of 2013, which devastated Boulder and surrounding towns. "If that storm centered on this part of town, that’s catastrophic damage," said Nancy Kuhn, a spokeswoman for Denver Public Works. Separately, she added: "The City’s goal is to provide the maximum protection against storm events that is possible and practical. Therefore, we design major infrastructure to address up to the 100 year storm where we can."

Moreover, Denver staff contend that the benefits for this project could eventually extend south, beyond just the areas highlighted above. This first phase will lay a "backbone," said Jennifer Hillhouse, project manager for the golf rebuild. Future phases (and spending) could connect more pipes to that backbone, allowing better drainage in those northeast Denver areas that currently don't see much change from the project.

One of Walsh's group's alternatives is to dam water on individual properties and allow it to seep into the water-table, which certainly would be unconventional. Walsh sees the entire system as a pointless exercise in bureaucracy.

"It’s a revolving door between CDOT and all of these expensive army of consultants. They want to have these projects on their resume," she said.

Question two: Why you gotta treat the golf course like this?

If you want to control a flood, you have to slow it down. The slower the water is flowing, the smaller your pipes can be. The smaller your pipes, the easier it is to build them.

So, the golf course's job in this system would be to trap floodwater and then slowly release it. City Park already does this naturally to some extent.

"Thank goodness City Park was built in the lowest part of the basin," Hillhouse said. Because part of the course is relatively low, water tends to collect there during the heaviest storms. This redesign of the golf course would encourage that by creating a topographical bathtub on its western end, because, again, captured water is easier to handle.

Critics say that the city plan would put a detention pond in the golf course. It's more fair to say it would very rarely put a detention pond there. Most of the time, you would expect to see just a stream running through the course. When it rains really hard, the bathtub might fill up for six to 12 hours before draining out into pipes and the streets.

The city rejected other locations because they either didn’t work well with the drainage patterns or they would have required buying up a lot of private property, staff said. Hillhouse said the city also considered creating multiple smaller detention areas but decided that would be inefficient and ultimately require more land in total.

But that doesn't mean the golf course project would be easy.

Tons and tons of soil would be cut from the western side of the course and moved to the eastern side. The top soil would be peeled off, the ground regraded, the greens and bunkers redone. (The city has compiled examples of other stormwater-detaining courses.)

It could take 18 to 24 months, closing the course through much or all of 2018 and 2019. It's a "pretty complete redesign and reconstruction," Price said.

The city also is considering moving the clubhouse from the northwestern corner of the course to somewhere in its center. The building currently stands in the way of a potential exit channel for water and gets flooded pretty often, according to city staff.

"The clubhouse was just built in 2001, and they're going to knock that down," Walsh said. She thinks that the relocation of the building is part of a plot to intermesh the golf course with the Denver Zoo, which is just across the street.

"The zoo is always looking to expand. The zoo is a cash cow for the city," she said.

Denver also would be messing with a bit of history, and some trees.

City Park Golf Course was built in 1913 to a design by Thomas Bendelow, the “Johnny Appleseed of American Golf.” It's renowned for its views of downtown and the way the swelling hill of its eastern half creates an illusion of infinite space. (The city has a little factsheet about how it's remaining consistent with the historic design.)

The city also could end up removing and replacing anywhere from 150 to 280 trees. This is a major point of contention with some critics of the project.

"They’re going to destroy one of the best rainwater conservation systems in the world, which is open space with trees - big trees, not little trees like they’re going to plant," Walsh said.

City officials say that they are planning to preserve the mature trees along the edge of the golf course and attempting to preserve some of the "significant" stands within the course. The ones most at risk "are tiny little trees and are not in good health," Hillhouse said. The project will be required to replace the canopy coverage that it destroys.

This is a concern for Historic Denver too, which noted in October that trees they believe to be historically significant haven't been identified for preservation. Some of those contested trees are diseased or susceptible to Emerald Ash Borer; Historic Colorado argues that isn't a reason to doom them.

Walsh's group questions whether the removal of those trees won't hurt the ecosystem's ability to process and clean runoff water. The city staffers acknowledge that trees do that but say that natural vegetation only handles small storms.

If you want to see which trees are most likely to die, try comparing this planning map with an aerial view.

What's next? Is this a done deal?

Mayor Hancock has given little indication that he would consider a change of plans. "We got to do a better job helping people understand the project, making sure people have good information," he said. He's open to ideas, but it would be "disingenuous" for him to entertain a movement away from either the I-70 rebuild or Platte to Park Hill, he said.

There's a lawsuit that claims the use of the golf course for flood control violates the city charter. While the city contends it is on solid legal ground, the lawsuit just cleared its first hurdle when a city motion to dismiss was denied.

The city already has taken out $206 million in bonds for Platte to Park Hill to be paid for by increased storm and sewer fees. Another $18 million might come from the city’s bank account, and $74 million could come from CDOT and the Urban Drainage and Flood Control District. The cost sharing is laid out in an intergovernmental agreement with CDOT, along with significant city obligations to the I-70 project.

The golf course project was never specifically approved by the council, but that's not uncommon for Denver projects. The city convened public meetings on July 30 and Oct. 25 to get comments and perspective on what this redesign should look like.

Those sessions dug into questions of course design -- where should the clubhouse be? How big should the practice area be? How wide should the fairways be? (See a summary of those questions here.)

To Hyde, one of the critics, the city's questions started too narrow. He wishes staff would have brought a blank map of the floodplain to the community and laid out more options. (The city started discussing alternative versions of this general plan with the public in August 2015.)

"The participation process, was very different than what I sought to do when I was working in watersheds where I didn’t live," he said. He wants to see the city create a stormwater advisory board, to ensure residents are always overseeing Denver's flood-control plans, among other suggestions.

James Rinker, a golfer who lives a few blocks from the course, said he hopes a redesigned clubhouse might make better use of its space, and he wants some par fives on the course.

"I think it probably needs to be done," he said. "I'm concerned with it being done right."

Becky Sharp, who formerly worked as a golf pro at the course, said it's well known for its tiny greens and severe slope.

"Mostly what the golfers say is, if you're going to disrupt my golfing life, give me a better product on the other side," she said. "It's a big deal that this golf course is not going to be available for 18 to 24 months."

From here, the city will embed the general ideas of the design into a request for proposals.

The city likely would pick two companies to act as a "design-build" team.

"Basically, you’re drafting the rules of engagement, the rules of design they have to abide by," Hillhouse said. Price described it as a more efficient, integrated approach.

However, some are concerned that it will leave the exact details unresolved for some time. For example, Historic Denver is concerned that it hasn't yet seen details of what the inlets and outlets to the course would specifically look like.

There is more time, though, for public input. The city will host a third community workshop mid-January. That's also when the city expects to publish the specific budget of the golf section of the project.

You can submit comments to the city via [email protected]. If you have a perspective to add to this story, get me at [email protected]