This is the question Denver is trying to answer: In what circumstances is it OK to build without providing parking?

Back in August, Denver City Council put a moratorium on the use of something called the small lot parking exemption -- which let developers skip the parking in mixed-use zones if their lots were 6,250 square feet or smaller -- after developers started to actually take advantage of the provision. The most controversial project is probably the 108 micro units that Pando Holdings wants to build at 16th Avenue and Humboldt Street.

A working group made up of city planners, parking and transportation specialists, developers, a historic preservationist and neighborhood representatives met five times to try to work out a compromise proposal.

In the end, neighborhood representatives thought the "preferred alternative" -- supported by Council President Albus Brooks and developers on the committee -- would allow too much housing without enough parking. Some even suggested it would be better to do away with the exemption entirely and require parking for all new development.

That means there's a fight pending at Planning Board and then again at Denver City Council over the next three months. And the debate will cover a lot of the same issues that led to the moratorium in the first place.

Speaking very broadly, there are two schools of thought here.

One is that we have a very basic choice: We can build for people, or we can build for cars. Space that goes into parking doesn't get turned into housing, and we desperately need housing. People have and increasingly use non-car ways of getting around, and we should encourage more of that rather than making sure cars are accommodated.

The other way of looking at the issue is that some car-free paradise is decades in the future, and we can't just ignore how people live now. Exempting projects from providing parking means developers can make more money -- by cramming more units into their lots -- while existing residents face the burden of overcrowded streets.

Why did the city exempt small lots from parking requirements in the first place?

The goal was to encourage the reuse of existing buildings and smaller scale development. If parking had to be provided on-site, developers might tear down an inconveniently located older building or consolidate lots and build a larger building just to make room for required parking.

The exemption has only been used once, but there are nine projects moving through the approval process, including the two-building, 108-unit micro-apartment project with no parking at 16th and Humboldt. The moratorium doesn't apply to those projects because they were already in the pipeline with City Council suspended use of the exemption.

The proposal developed by the working group would require parking for projects larger than two or three stories.

Here's what's on the table: You wouldn't have to provide any parking for existing buildings, no matter how the use of the building changes. For new construction in mixed-use zone areas along transit corridors, the first three stories wouldn't need parking. In areas without good bus or light rail service, the parking requirement would kick in after the first two stories. Anything taller would have to provide parking for those extra stories.

The principle here is that if there is decent transit access, people have better alternatives to driving, so it's okay to go up to three stories without providing parking. But with or without transit, as buildings get bigger and taller, chances are at least some of the people using that building will own cars and drive to and from those buildings.

Under the city code, there are a variety of ways developers can reduce their parking obligations, like building senior or affordable housing, building near bus service, offering enhanced bike parking or providing car-share service. Developers haven't been able to just cancel out their obligations entirely, though. The reduction is capped at 50 percent of what would generally be required.

The new proposal would allow developers to eliminate any parking requirement by taking various mitigation steps, though city planners said it would be difficult to get to a 100 percent waiver.

Taking the Humboldt Street micro-unit project as an example, here's how this looks in practice. Right now, using the exemption, the project isn't providing any parking on-site. If the same project were to come through under the new proposal, it would have to provide 10 spots for 108 units. If the parking exemption for small lots didn't exist at all, the project would have to include 26 spots.

"This threads the needle," Brooks said. "This provides parking opportunities for neighbors. At the same time, it doesn't overburden the developer and drive up the price per unit."

"Not everyone is happy with this proposal," Brooks acknowledged.

Specifically, four neighborhood representatives on the group said they don't have enough information to assess the impact of the change, and they fear certain development patterns could mean neighborhood streets would still end up overcrowded.

For example, it's one thing to have one micro-unit project on a block and absorb whatever extra cars that generates. It's another to have two or three or four.

"Just like you say you can't have 10 bars in one block, you can say you can't have a bunch of these in one block," Craig Vanderlan, president of the Humboldt Street Neighborhood Association, said Thursday at the final meeting of the working group.

In an earlier interview, Vanderlan said the proposal doesn't do enough to recognize differences between neighborhoods.

"Some neighborhoods are very much transit, car-free oriented and want to support the movement of Denver to a transit mecca, which we're a long way from," he said. "We would like to see that as well, and as we get closer to that, this will have a lot less impact, but we're not there yet."

Neighborhood representatives also want more notification and opportunity for input on individual projects.

It's not totally clear what the impact of these changes would be.

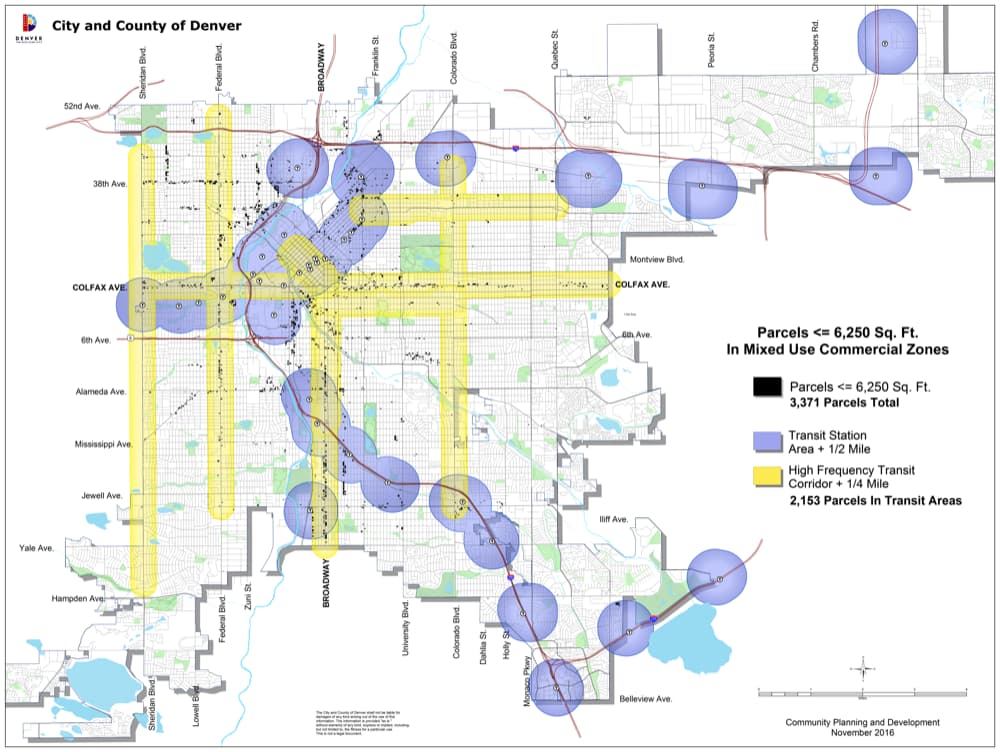

There are 3,371 parcels in the city to which the small-lot parking exemption could apply. More than 2,100 are within a "transit shed" and could be developed up to three stories with no parking. About half of those lots have zoning that doesn't allow them to go beyond two or three stories and about half could be taller.

Outside the transit-shed, there are 1,247 parcels, 80 percent of which could go taller than two stories.

City planners don't have detailed information, though, about how likely redevelopment is on each of those parcels and what that could look like in terms of uses and numbers of units.

So, depending on your perspective, that's a lot of potential development whose impact is poorly understood, or that's a lot of potential development that now will have to provide some parking, whereas before, it didn't have to provide any.

Historic Denver Executive Director Annie Levinksy said her primary concern is not accidentally creating an incentive to tear down old buildings, but there may be an additional advantage to exempting parking for two- and three-story buildings but not for taller ones. That might encourage more developers to build smaller structures that won't overwhelm the older buildings around them.

Barry Hirschfeld, a Denver businessman and philanthropist who is partnering with Pando Holdings on the Humboldt Street project, said no one should assume every lot will be developed to its maximum capacity or that every lot that could avoid parking will.

Developers still have to find financing and convince investors that people will want to live in the building, and in some cases that will mean providing parking.

"I don't think this is going to have a devastating impact on Denver neighborhoods," Hirschfeld said. "Remember there are some constraints built into the system."

Brooks had hoped to emerge from the working group with consensus.

That wasn't to be. Four neighborhood reps said they are "hard no's" on the plan.

But the clock is ticking on the moratorium, and City Council needs to act. The working group is done, and Brooks' preferred alternative will be turned into a draft ordinance.

Next steps:

Jan. 2: A draft plan for public review will be released.

Feb. 1: Planning Board will discuss the proposal and make a recommendation.

Feb. 27: Denver City Council will hold a first reading of the ordinance.

March 27: Denver City Council will hold a public hearing and second reading. This will be the final vote.

March 31: The moratorium expires.