The odds of a white Christmas in Denver seem to be receding this year, with the National Weather Service forecast now saying "mostly sunny," but over the last 50 years, the likelihood of having some snow on the ground during the Christmas week seems to be going up.

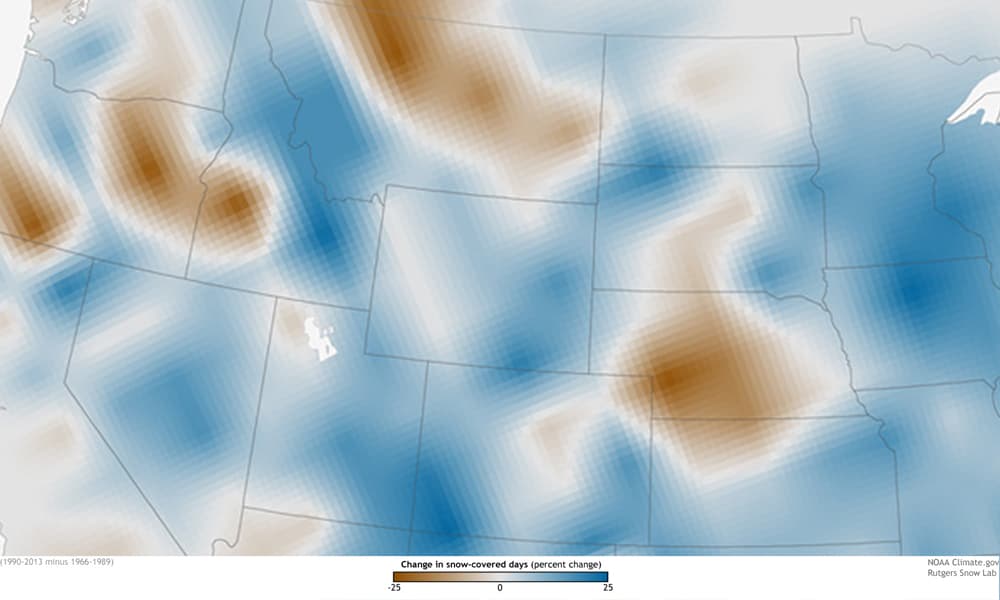

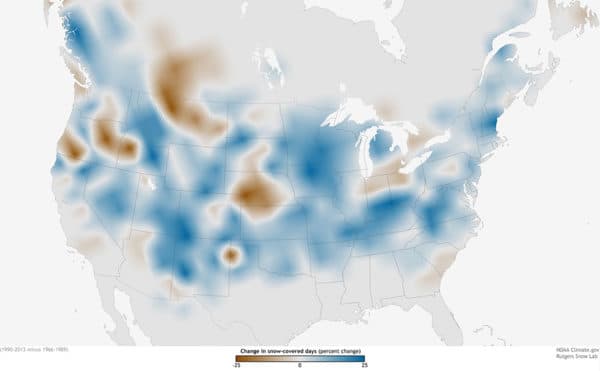

Back in 2014, Rebecca Lindsey, a science writer and editor for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, worked with researchers at the Rutgers Snow Lab -- which uses NOAA satellite data -- to look at whether there was snow on the ground during the holiday week for the period from 1966 to 1989 and then again for the period from 1990 to 2013. In much of the country, including in much of Colorado, there was an up to 25 percent greater chance of having snow on the ground around Christmas, as indicated by the blue shading.

For the Denver area in particular, though, there doesn't seem to be much change. (You can see that as the white blotch over our part of Colorado.)

What does this mean?

"According to the Rutgers’ folks, there seems to have been a modest increase in snow extent during the holiday week today compared to the past for the country as a whole, although it clearly varies a lot from place to place," Lindsey wrote. "Further, the scientists emphasize, singling out a particular winter week for scrutiny isn’t especially meaningful as an indicator of long-term climate change."

Think about it this way: If a big storm comes in early December but has melted by Christmas or if a big storm comes in early January, it's not more or less significant than one that comes near Christmas.

Christmas is a social construct. Jesus was probably born in the summer. Or the spring. Or the fall. There are many theories, but none of them point to Dec. 25.

Monthly and seasonal averages are a better way to track long-term changes, Lindsey said.

Klaus Wolter, a climatologist and research scientist at the University of Colorado Boulder, said in an interview that snow patterns in Colorado are heavily influenced by El Niño and La Niña systems, and it's hard to pin changes from year to year to global climate change.

After he told me this, Wolter added, "My impression is that it's easier to get rain mid-winter, and that fits the you-know-what theme." Before the snow evaporated from the Christmas 2016 forecast, there was a decent chance the precipitation was going to end up as rain.

The El Niño and La Niña cycles themselves are affected by climate change, but it's a lot more complicated than saying that it's getting warmer so there's less snow or some pattern has changed so there's more snow.

Earlier spring melting of snow is pretty well documented. That could be because of climate change or because of the dust that travels around the world and settles on our snowpack, causing it to absorb more sunlight and melt more quickly -- or a combination of the two. Both would be man-made causes for less spring snow cover.

The state of snow in late fall and early winter is less well understood.

Wolter said it does seem that for both Eurasia and North America as as a whole, there's a greater chance of putting down snow early in the winter. No one really knows why this might be or whether it's related to climate change. But one idea that's been put forth is that lack of sea ice is causing a massive lake effect off the northern oceans.

Lake effect snow, per the Weather Channel's helpful explainer, occurs "when cold, dry air picks up moisture and heat by passing over a relatively warmer lake." It's more common in late fall and early winter.

Wolter said that's more plausible for Siberia and other parts of Eurasia than it is for North America, and it hasn't been well tested or modeled.

Wolter urges some caution in looking at historical snow data. Where and how people measure snow has changed over time, and there are some eras where researchers were less -- let's say diligent -- than in others. And things like moving a weather station from Stapleton International Airport to Denver International Airport, some 15 miles to the northeast, can create apples and oranges issues with your historic snow totals.

Satellite data like that used by the Rutgers Snow Lab is much more consistent, but there are still issues where a thin layer of snow cover won't show up in the images, Wolter said.

We're in a La Niña system right now.

The characteristics of La Niña are dryer springs and falls, a greater chance of rain from December to February and huge swings in temperatures, like we just had last week.

The pattern also is associated with heavier snow in the northern and central mountains in Colorado.

"We have just seen that on steroids," Wolter said. "We went from one of the lowest snowpacks ever to normal, which meant we had 200 percent of average for the last four weeks."

El Niño years, in contrast, are associated with heavy, wet fall and spring snow and drier conditions from December to February.

Historically, there's a 15 percent chance of snow falling on Christmas Day in Denver.

That's according to the National Weather Service, which has lots of historic snow data. And there's a 38 percent chance of having at least one inch of snow on the ground on Christmas Day.

The Christmas record for snow on the ground belongs to 1982, with 24 inches.

The most snow to fall in Denver on Christmas Day was 7.8 inches in 2007.

You can compare our chances of a white Christmas to the rest of the nation's here.