The city of Denver has slowed its practice of temporarily banning alleged drug users and dealers from its parks. As of last week, police officers had not issued any parks "suspension notices" since Nov. 8., according to Denver police.

However, the city has not discontinued its use of the new policy. Cyndi Karvaski, parks spokeswoman, said that enforcement has been less necessary because of cold weather and an apparent drop in public drug use.

"We really need to do a more in-depth analysis to determine the effectiveness" of the policy, she said. "We have seen, possibly, a change of behavior."

The American Civil Liberties Union, meanwhile, is defending a man who faces criminal charges for returning to Commons Park after being banned for alleged marijuana use.

The ACLU argued in a Dec. 23 court filing that the bans violate the U.S. and Colorado constitutions. This morning, the organization issued a letter calling on the city to end the policy.

Background:

Parks director Happy Haynes announced the new bans policy in August, capping a summer of news reports about heroin use along Cherry Creek and violence on the 16th Street Mall. The policy allows police officers to issue immediate three-month bans to anyone suspected of using or distributing drugs in city parks.

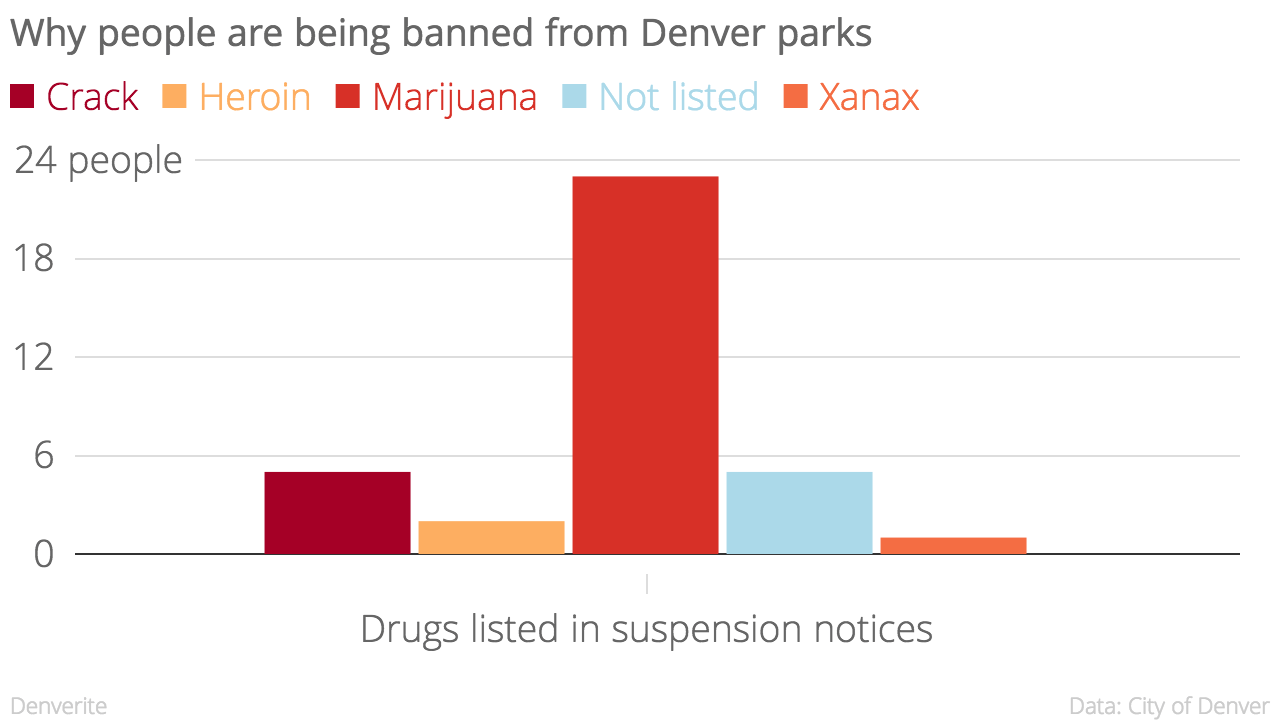

Officers have banned 40 people, according to DPD. That group includes everyone from alleged pot users in Commons Park to a man who had needles but no actual drugs in Lincoln-La Alma Park.

Troy Holm's case:

Holm, 23, was sitting with a group of people on the so-called Stoner Hill in Commons Park one day in October. Among them was an undercover police officer, according to a police document.

Shortly afterward, another officer approached Holm and ticketed him for having marijuana in a park, then gave him a document saying he was banned from Commons Park for three months.

Three days later, a third police officer spotted Holm in Commons Park. The officer "did not observe Mr. Holm engaged in any illegal conduct," according to a motion filed by ACLU-affiliated attorneys.

Still, the officer believed Holm was there in violation of the notice and charged him with violating the city ordinance. Later, the city's attorney office added a charge of trespassing.

The ban, according to the defense's filing, cut Holm off from his "chief source of community." Stoner Hill, which I've previously profiled for Westword, is a place for him "to spend time with friends who have become his only family."

Commons Park also is a focal point for the distribution of food and services, as the motion notes. Disobeying a parks ban can result in a fine of up to $999 or up to a year in jail.

The defense's argument against the policy:

The filing argues that Denver's laws do not give the parks department the power to issue temporary bans. The department can ban certain activities, the defense argues, but not certain people.

The ACLU filing also cites a U.S. Supreme Court decision from 1999 which describes an "individual's decision to remain in a public place of his choice" represents a fundamental freedom. (In that case, the court overturned a Chicago law that allowed cops to ban suspected gang members from gathering in public.)

Of course, this also resembles the fight over Denver's "urban camping" ban and the ongoing lawsuit over its relocation of homeless people and their belongings from public sidewalks.

The filing also states that the policy gives officers "virtually unrestricted authority" in banishing suspected drugs users and does not describe a standard of proof.

As the policy itself states, someone can be banned without being "charged, tried, or convicted" of any wrongdoing. And while appeals are allowed, they are impossible for anyone who can't provide an address or an email address, according to the defense's filing.

The defense argues that for these and various other reasons, the municipal court should dismiss the charges. If they succeed, it could be a serious problem for enforcement of the new bans policy.

In announcing the policy, a city press release said its purpose was "to protect public health and parkland, increase safety and improve the overall experience for trail users," specifically noting the prevalence of heroin on Cherry Creek Trail.

The policy is set to expire on Feb. 26. Karvaski said the department is confident it had the authority to create the rule, and soon will decide whether to make it permanent.