Denver Parks and Recreation will propose a permanent policy allowing the city government to block people accused of using drugs from accessing certain public parks.

Currently, the city allows police officers to ban anyone they say is using drugs in a public park from that park for 90 days. A Denver County judge recently wrote in an order that she wouldn't allow the punishment of a man who violated the ban because the policy is "unconstitutional."

That order did not, however, strike down the policy, and there's no sign the city intends to end the policy.

"Denver Parks and Recreation will continue to address the issues of illegal activity and unsafe practices in our public parks," spokeswoman Cyndi Karvaski said in an emailed statement.

The department will propose a permanent rule and regulation on "the temporary suspension of the right to access parks," she wrote. The current, temporary version of the policy is set to expire on Sunday, Feb. 26.

It's unclear what the new version of the policy might look like, but I've requested more detail. Any permanent version will take into account the recent loss in court and public comment, according to Karvaski.

Any new rule would go through the Parks and Recreation Advisory Board and a public hearing before it could be approved by parks director Allegra "Happy" Haynes, Karvaski wrote.

Here's how the American Civil Liberties Union successfully challenged the policy in court:

The nonprofit argued that it deprives people of their access to public parks before they're allowed to present evidence or challenge the police officer's judgments.

Yesterday, a Denver County judge found that the process in place could keep a wrongfully accused person out of a park for weeks. In more legal terms, it denies them due process because they have to wait weeks before they can challenge the police officer's decision.

The ACLU argued that this could deprive homeless people in particular of friends, family and other resources in the parks.

The judge dismissed criminal charges against a man who had been accused of violating his suspension. However, the judge's order did not strike down the policy.

One way the city could try to resolve the judge's issues: Make the bans effective after people have a chance to challenge them.

Previously, parks spokeswoman Cyndi Karvaski said the statistics may show the program is successful: No officers have issued bans since 2016. Don Cohen, president of the Riverfront Park Association, said earlier that the city's use of the bans seems to have driven a young and largely homeless crowd from Commons Park to nearby Cuernavaca Park, accomplishing a longtime neighborhood goal of clearing "Stoner Hill."

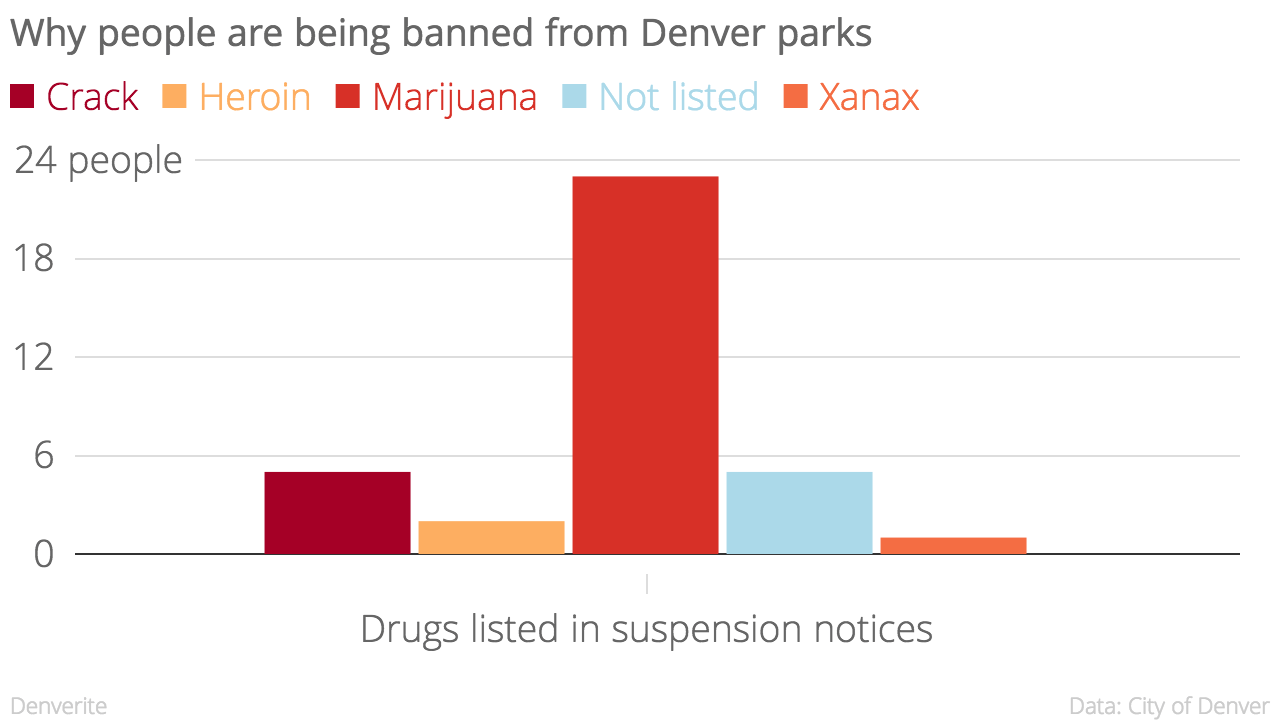

Practically all of the people who have received the bans said they lived outside or in shelters, according to police records, and most were accused of using marijuana in the park.

About 40 people had been suspended as of November, but the city essentially hasn't used the policy since then. Earlier, Karvaski said that cold weather may have reduced the need for the policy over the winter, and that it appeared effective so far.