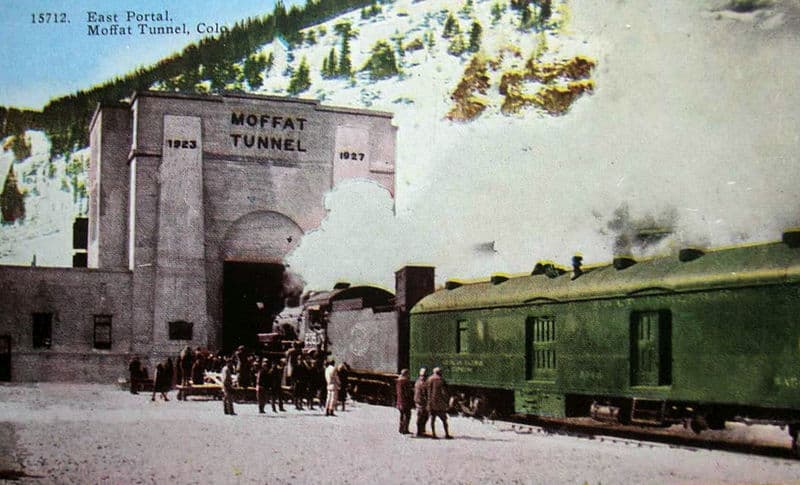

It was 1923. Work was just beginning on one of the most ambitious projects the West had ever seen: a six-mile tunnel to pierce the spine of the Rockies, uniting the Western Slope and Denver as never before.

First, though, the designers had a decision to make: What would they put at the entrance to the Moffat Tunnel?

It had to be grand, obviously. This project was bound for national attention. President Calvin Coolidge himself would years later touch a golden key to a wire in the White House, setting off the explosives that completed the connection. The tunnel is still in use today, passed through by freight trains and the Winter Park Express alike.

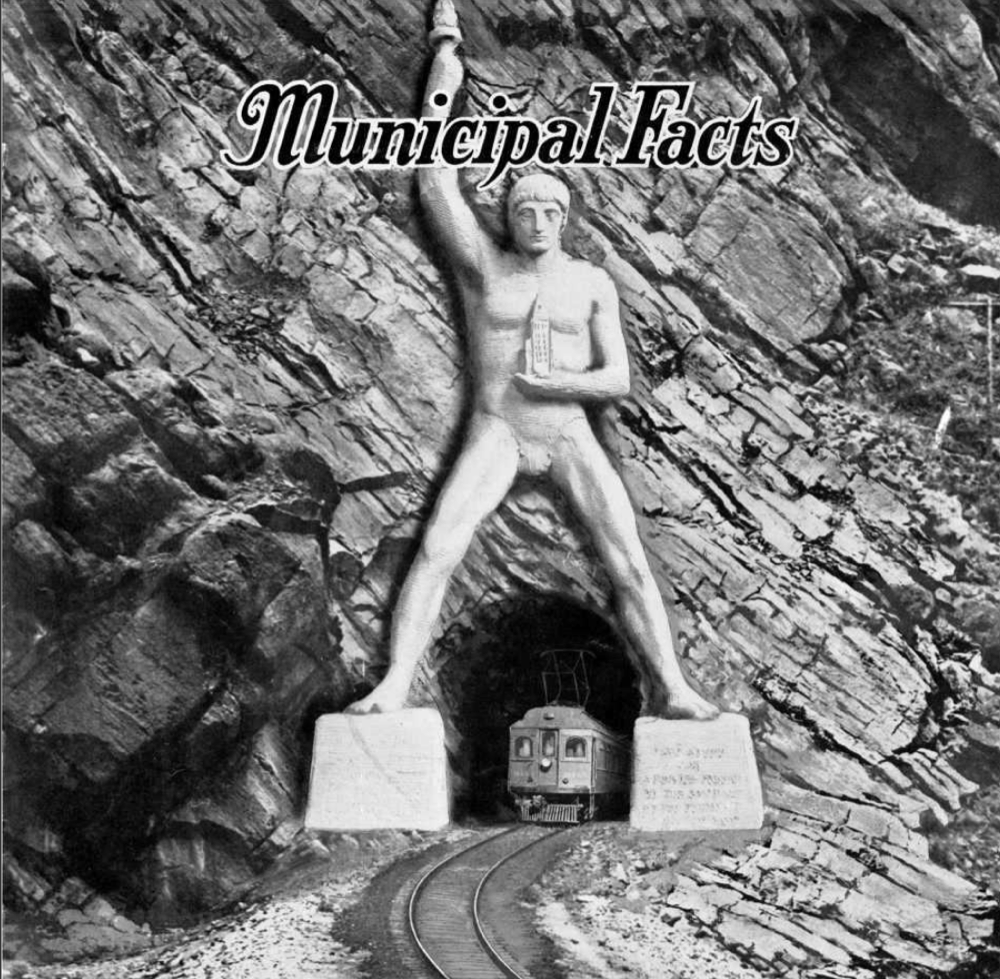

So, anyway, some influential people in Denver had a little idea for the perfect finishing touch. How about a giant, naked and anatomically vague dude holding what appears to be the 16th Street clocktower in one hand and a torch in another? How would that be?

The image above comes from the cover of a 1923 edition of Municipal Facts, a news magazine that was published by the Denver government. The publication dedicated a page and a half to promoting this huge nude "colossus," as they called it.

Actually, they wanted two - one for each entrance. This was the vision of the sculptor Robert Garrison, a 28-year-old sculptor who was gaining fame in town for his sculpture of the goddess Minerva in the Morey Junior High School auditorium.

"It is Garrison's plan that such a colossus be carved from the rock at each portal of the tunnel, or, if that is not possible, that they be carved from native Colorado granite and erected over the tunnel openings in such a manner as to seem as though emerging from the solid rock background," the paper printed.

In fact, these would just be two in a "series of great figures" that would be at intervals from the Statute of Liberty to the Golden Gate.

"America would then have a series of great sculptural works, each of which would carry aloft the torch of liberty and enlightenment, to typify the march of civilization across the North American continent," Municipal Facts printed, reflecting a Manifest Destiny colonial attitude. (On the previous page of Municipal Facts, there's a "Hymn to Colorado" that includes the line "Long ago the paleface wooed her.")

The colossi were supposed to be 100 feet tall – and the most bombastic part may have been the plan to unveil them. They were to be draped with the flags of every state in the Union. At the appointed time, an airplane "would swoop down from the sky, catch a projecting wire loop with a grappling hook and thus snatch the entire sheaf of flags from the figure, trailing them over the heads of the spectators in his return flight."

Honestly, it feels like a lot could go wrong with that plan.

It's unclear exactly how much further this idea ever got. Garrison would go on to some fame, as Municipal Facts predicted he would. His work in Denver includes a frieze at the botanical gardens and the twin cherubs riding sea lions at Civic Center Park. He even got to design some giant people that still stand at Boston Avenue Church in Tulsa.

Moffat Tunnel, however, got nothing quite so exciting.