Nancelia Jackson has lived in Cherry Creek for 91 years. She arrived in 1926 and can attest to just how much the neighborhood has changed in that near-century. From its transformation as the home of Denver's city dump to the chic shopping district we now know, Jackson has watched its history unfold.

As the neighborhood became upscale, so did Jackson's home. In her story as in others, owning property is a key factor in upward mobility, a familiar topic these days as the city grapples with gentrification.

Today, Jackson lives in a modern duplex on Garfield Street that stands on the same plot where she and her husband built their first duplex in 1954. It's just next door to the address where she grew up.

Sitting at her dining room table, she tells the story.

At the beckoning of her grandfather, she and her mother moved here from Chicago in the '20s. A serial builder, William Pitts constructed a number of homes in the neighborhood, including his granddaughter's, one of which still stands at 563 Harrison Street. Pitts also helped found the African-American resort town Lincoln Hills, where the family still uses the cabin he raised.

Back then, Cherry Creek was sparsely dotted with homes - few enough, said Jackson, that you could count them all with one hand.

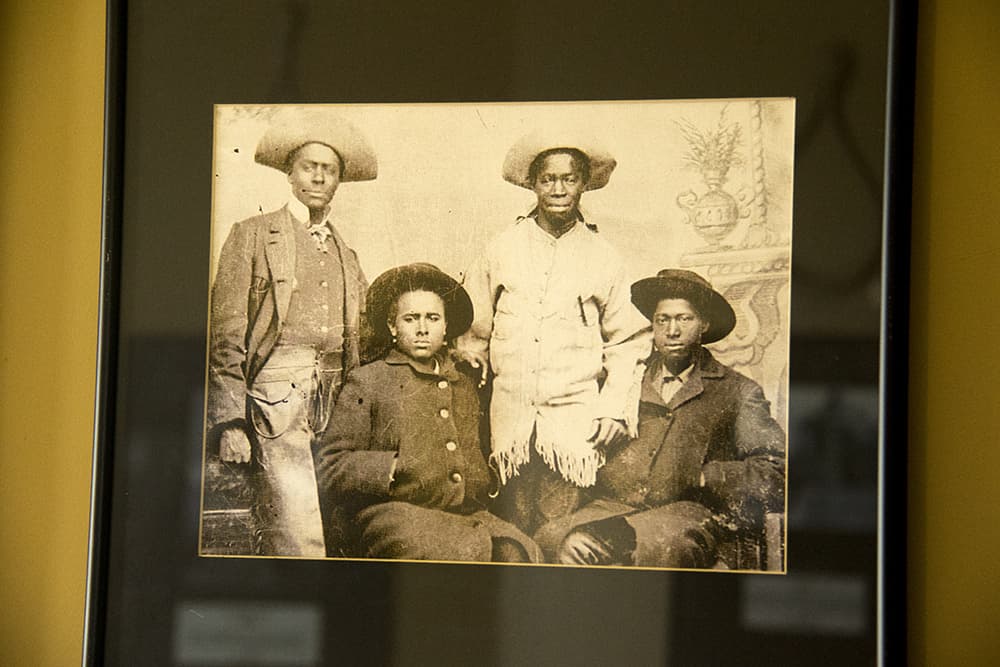

The area began as Harman, a separate town, and was annexed in 1895. The low area around the Cherry Creek was the legacy of black homesteaders, like the ranching Parker brothers, who arrived in the late 1800s along with so many others heading west. By the '20s it was considered a suburb and still largely an African-American neighborhood.

"Cherry Creek had like a little colony of black people," said Jackson. "We were here first."

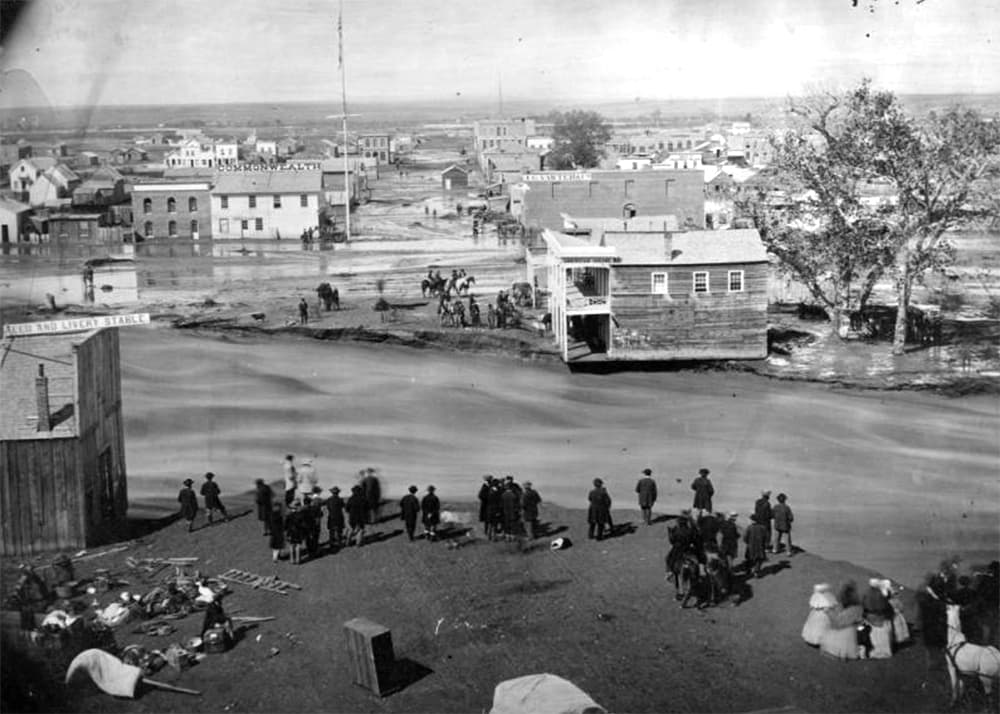

One reason the area remained segregated in its early era may have had to do with local conditions. Before the Cherry Creek Dam was completed in 1950 the whole area was prone to regular and often destructive flooding. William Pitts had the foresight to build on high ground, and Jackson can remember watching homes go under floodwaters from the hillside.

But she and others remember the area in a positive light. The way she tells it, Cherry Creek felt far removed from downtown. She says she never even noticed the city dump to the south.

A history of the neighborhood from 1976 remembers that heap with glory. It was a place for hunting "treasure" containing "a mixture of garbage, crankcase oil, and other smelly and sticky things," where kids discovered materials from which to build clubhouses and "children scavenged ... bottles, tires, and other discards to sell to the many rag men who drove their horse drawn wagons up and down the alleys."

But not everyone shares this rosy outlook.

"There are two sides to every story about the dump," said Terri Gentry, a historian at the Black American West Museum. "You don't hear very positive discussion about the dump from black folks who were being pushed out."

I asked Jackson if she felt like her childhood proximity to the site was a sign of inequality; she just shook her head. After all, she was just a kid, and her memories are happy ones. She only remembers having fun at the Esquire Theatre and not, as her son Gary reminds her, having to sit in the segregated balcony upstairs.

When the neighborhood began to integrate after a post-World War II housing boom, Jackson did not feel any conflict or tension, she recalled.

By the 1950s, Temple Buell had replaced the dump with the first edition of the Cherry Creek Mall. The dam had ended the flooding and allowed the newly expanding community to securely take root. Brick bungalows and duplexes like Jackson's quickly filled in the empty space.

By 1990, Buell's mall was in turn replaced by the structure that you know today, touting high-end outlets like Neiman Marcus that upped the area's prestige. In 1994, Jackson "scraped" her lot and built what Gary says was the first high-end home on the block.

"I saw it turn all around," his mother recalled.

The home William Pitts built on Harrison sold for $16,000 in 1955, Gary said. When it changed hands again in the '90s, it went for something closer to half a million.

In a century, the Jackson's quiet African-American community had become Denver's upscale neighborhood, bringing homeowners who stayed up with it.

Up, at least, in a financial sense. For some people, like Jackson, economic growth might not always mean improvement. She misses a time when this was a closer-knit community, when the corner store delivered groceries and everyone knew each other.

And, of course, Jackson was lucky to own property in the first place. African Americans have historically been 20 percent less likely to own homes since 1900, a gap that's persisted to the present. Black homeownership has been even lower in Denver.

But regardless of its status, Nancelia Jackson is quite affectionate of her little slice of Garfield Street. This has, and always will be, home.