Last week marked a milestone for "right to rest" activists in Denver. A jury of six ruled unanimously that Randy Russell, Terese Howard and Jerry Burton were indeed guilty of violating the city's urban camping ban, a controversial rule that prohibits people from using any shelter on Denver's streets. Also this week, two state representatives introduced a bill that would outlaw such policies at the state level.

I'd been covering events surrounding this controversy even before Denverite existed. This week seemed like an appropriate time to revisit how we got here as activists and officials ponder where things might go next.

It would be folly to say that all of this started at any one event. But there was a moment early in 2016 when the city's so-called "sweeps" became highly publicized. I covered that event for Westword. For me (and probably other Denverites) this initial wave of sweeps was an introduction into ongoing friction between desires to keep the city clean and to help people in need.

The city's spring cleaning opened up a lot of questions for folks trying to wrap their heads around the situation. Why are people living on the street in the first place? Why not a shelter? Is there some form of homelessness that is socially acceptable? Is it a choice for some people? What about the trash? What about drug use?

In August attorney Jason Flores-Williams sustained the controversy by making a high-profile show of his intent to sue the city over the March sweeps in a class-action case over how the city handles the belongings it seizes.

In October he and a handful of supporters entered federal court to make their case, specifically calling to depose Mayor Michael Hancock. This suit has yet to be resolved, though Hancock has avoided a deposition for now.

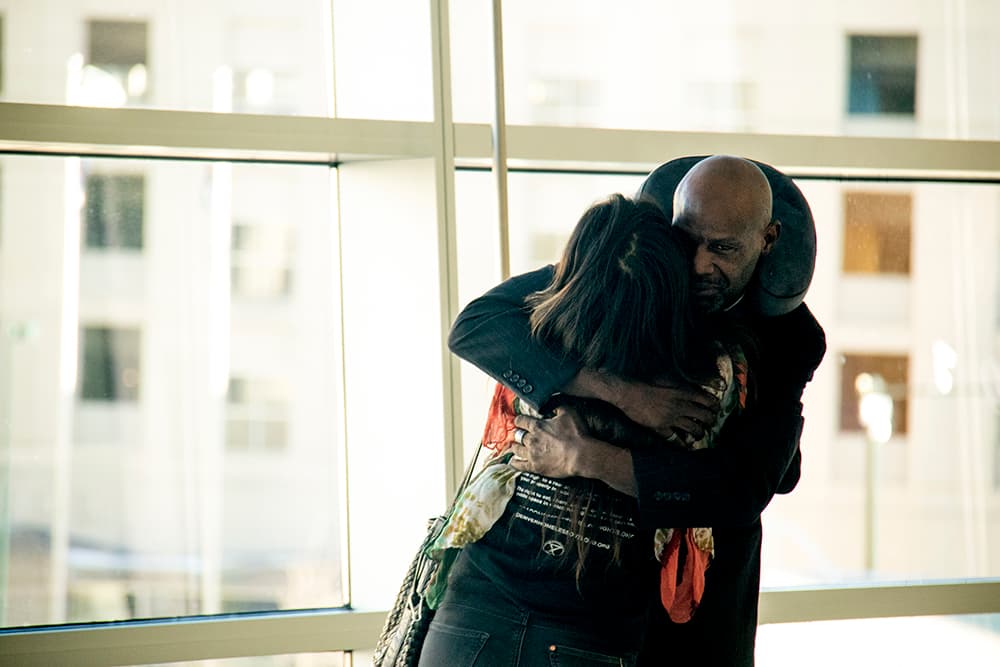

It was on this occasion that I first met Jerry Burton, a military vet who had been living on the street. He'd become one of the three defendants in last week's trial.

Burton has an interesting perspective on things that has stuck with me. As a vet, he feels wronged that the country he served has not taken care of him. As a black man who knows his history, he seems to be unsurprised that he's gotten the short end of the stick. As a staunch believer in God, he feels he's being divinely directed to help make things right, and that keeps him going.

Meanwhile, the city seemed to react to a hailstorm of negative stories about their dealings with its homeless. In November, Hancock invited press to the City and County Building for his unveiling of Denver Day Works. The day labor program offers work experience that might lead homeless residents to permanent work, which might lead to a permanent place to live.

This is Danny Tims Jr., a recent arrival to Denver. I know three things about Tims: he loves eyes, he's very proud of his son, who is a mixed martial arts fighter, and he recently kicked a drug addiction. Tims was looking to find some stability in Colorado. His smile below with the shovel shows how he saw himself on the right track that day.

I ran into Tims a few months later, and he told me he'd landed a full-time job and got himself into an apartment. The rent was high, he said, but things overall were going OK.

But despite some good faith and better optics, the city continued to raise the ire of critics as they cleaned up large homeless camps. Sweeps continued into 2017 near the Denver Rescue Mission and in RiNo near the Crossroads shelter, which is under a city deadline to fix code violations.

As the city sees it, isolated camps are a public health nightmare. City officials say they've cleaned up hundreds of used needles from camps and that pregnant women are found in dangerous squalor. Indeed some of the "swept" I spoke to sounded haunted by a rash of recent overdoses. The debate over camp sweeps come as heroin use has skyrocketed.

The conflict between homeless people and city officials came to a head on the Nov. 28 and 29, 2016, when a small group of activists set up camp outside of the City and County Building after being ticketed near the Rescue Mission. This was the night Howard, Russell and Burton received charges that they would take to court.

I stayed out there in the cold until 2 a.m. watching the protesters eventually get pushed out. The police did their jobs respectfully.

One officer, Jason Rivera, seemed to be the point person for communication between campers and authorities. He approached people with a kind tone as he asked them to leave.

I think Rivera occupies one of the toughest spots in this whole story, right in the middle of two extremely willful forces. I think he genuinely was interested in the protesters' health and safety while he was doing his mandated job.

It was also clear Rivera could see a bigger, more complicated picture. On one hand he seemed to understand these protesters just wanted to be left alone. On the other he could see that narcotics use and violence have been allowed to fester in unregulated spaces.

I think people understand those conflicting issues, but many people still had a really hard time getting behind the city choice to deal with it by confiscating blankets on cold nights.

Denver Homeless Out Loud has been the loudest voice advocating for the right to rest. Their arguments center around a dearth of affordable housing and poor shelter conditions that make living on the street a necessity for some. But as I experienced each episode of sweeps, I got a sense that the conflict is about something larger, something to do with what the government can and can't have domain over.

When winter arrived, I wanted to get a sense of how people got along in the cold. In December I actually brought my own tent to camp with Denver Homeless Out Loud's Ray Lyall during a considerable snow storm. People I met that night seemed to be OK in their tents. They probably were a little stiff in the morning, but a few layers of cardboard and thick blankets did the trick for the most part. I did not fare so well and staggered home at 3 a.m. nearly frozen.

It seems crazy that people like Lyall are fighting for the right to live in those conditions. City officials say it's inhumane to allow people to live on the street, that it's a problem that needs to be solved.

To Lyall, the problem is not his living conditions. Society's the one with the problem.

He said to me once, "Why do I have to have housing? Why do I have to have a job? So I can look like you? Does that make me a better person?"

He read the Communist Manifesto around the time he became homeless. He hasn't looked back since.

Lyall is probably a minority when it comes to this line of thinking. There are plenty of people out there who have ended up on the streets because of economic misfortune, mental health problems and addiction, not to mention Denver's expensive housing market. But his ideas highlight the fact that there are conflicting visions about what the city and its society should look like.

The Ballpark neighborhood in particular is a case study in that conflict. On one block you have nice new apartments for people who can afford to live in a trendy historic district. On another, you have multiple facilities for Denver's poorest.

I really felt that divide in November when I photographed a sweep and took a break to eat at a trendy breakfast joint on the same block. There's no doubt that people sleeping on the street doesn't fit the vision that downtown's commercial interests are hoping to sell.

The closest anyone's come to agreeing on a long-term solution for this conflict has been in the idea of some kind of tiny home village. It's been discussed and dismissed before, but a new plan is actually making progress for a tiny home site in RiNo.

In the meantime, advocates hope to see the law enforcement side of things dealt with in the state bill or the class action suit. Both face uphill battles.

Russell, Howard and Burton's court date finally arrived during an unseasonably warm spring that was punctuated by a freak snowstorm. It was a bizarre reminder of what the group has been fighting for: the right to live out in the cold -- and all the baggage that comes with it.