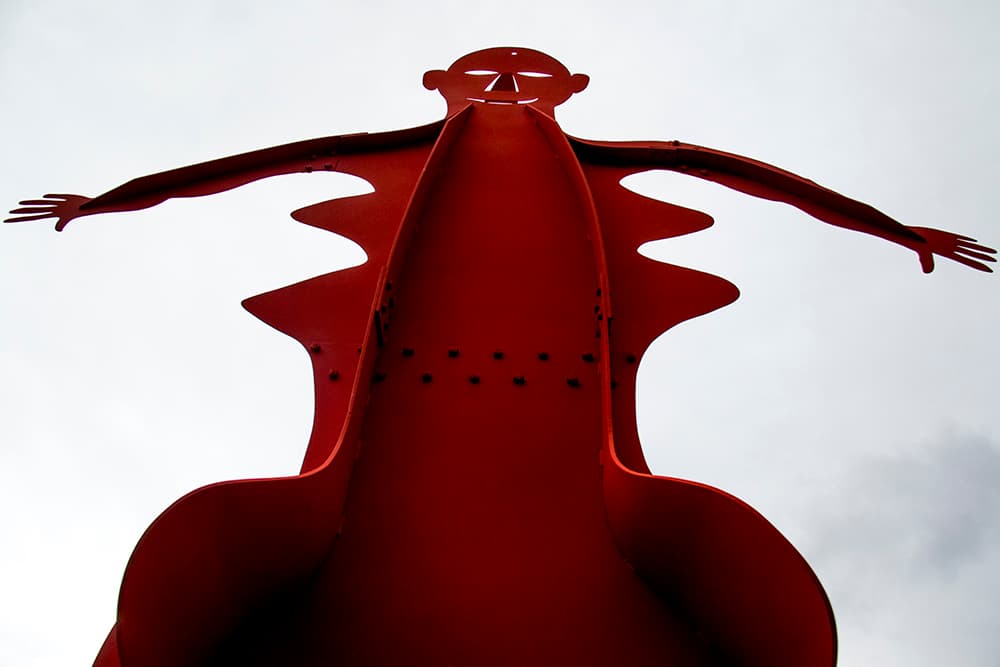

Today a collection of American artist Alexander Calder’s sculptures are officially open for viewing at the Denver Botanic Gardens.

The sculptor said to have injected hanging mobiles into the art world for the first time often worked big, using bold colors and materials to create massive, powerful figures. Many of his forms were inspired by nature; often designed for urban plazas, they are seen as a way to bring organic shapes to a city’s urban geometry. But the show’s architects see this collaboration between the gardens and Calder’s estate as a welcome departure from those man-made spaces, one that shows how the artist’s versatile work holds up anywhere.

“Some work could be destroyed easily by the environment,” said curator Alfred Pacquement, the former head of Paris’ National d’Art Moderne at the Pompidou. He's been active in Calder’s body of work for the last 20 years working closely with the Calder Foundation, and has been studying Calder's portfolio for his entire career. Both in terms of materials as well as a sculpture’s abstract, visual success, he says Calder has created pieces that can stand up to anything.

“It’s a confirmation that the work is strong.”

From towering work that peeks above the tree tops to massive metal slabs softened by spring blooms, Calder's sculptures compliment and contrast the Garden’s organic offerings.

“Engagement with the environment is the principle of these outdoor sculptures,” says Alexander "Sandy" Rower, Calder’s grandson and the founder of the Calder Foundation, who watched the artist work in his studio when he was a child. It’s also about the audience’s interaction with the work and its setting together, he said. “It’s this whole collaborative experience he wants you to have.”

And that’s kind of the idea behind any exhibit at the Gardens, an exercise in revising perspectives on art and nature by shaking things up a little bit.

“You change your environment and it makes you notice things differently,” said Lisa Eldred, director of exhibits for the Gardens. By placing work among the trees, surrounded by tulips or above a body of water, she says, we change our understanding of both the art and the natural world.

That’s something tied directly to art and human history, she said. Think of cave paintings. “There’s always been that intersection.”

Though the Gardens' mission includes an emphasis on science and research, it’s sometimes also just about the pure and simple joy of basking in something beautiful. After all, Eldred refers to it as a “living museum.” Here the natural forms that modify Calder’s work are themselves considered sculptures, artist-less works that are in turn enhanced by this exhibit.