Here's a view of Denver we'll never see again: It's downtown in the 1920s, as captured in an early aerial image. At the center is the Daniels & Fischer tower, still the tallest thing in the neighborhood. 16th Street runs from bottom left to top right, and Cherry Creek is at top.

Within 50 years, half of these buildings would be torn to the ground. Here's how.

This 1976 aerial photo captures downtown Denver at its emptiest, nearly 10 years into the historic (and somewhat infamous) Skyline Urban Renewal Project.

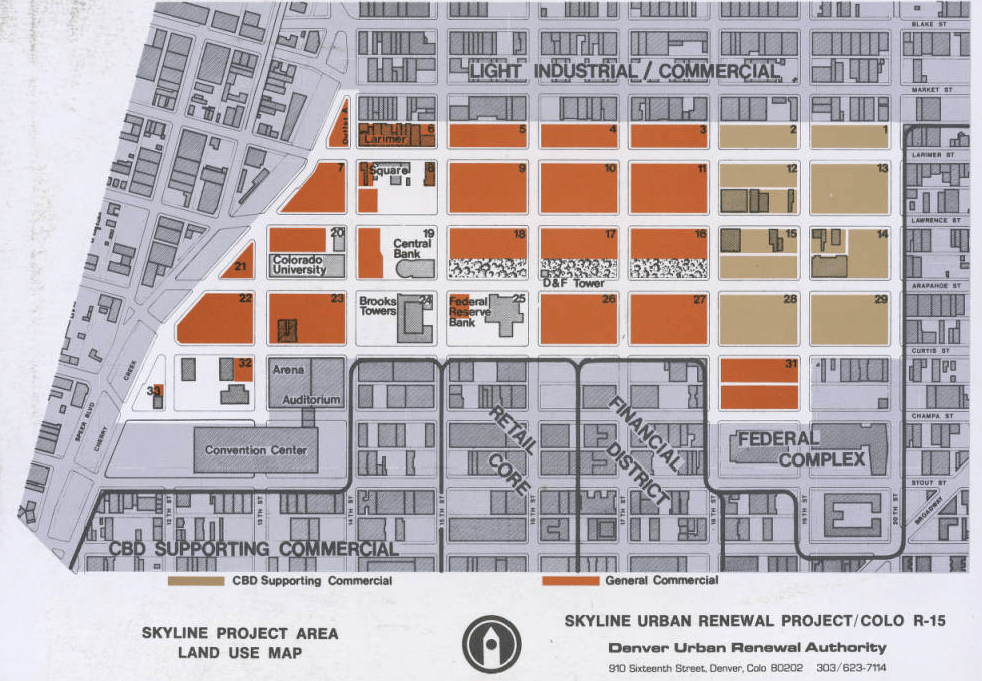

Voters in 1967 had overwhelmingly approved the Skyline plan "to demolish 120 acres of downtown for the promise of gleaming new towers," as Mark Barnhouse wrote in "Denver's Sixteenth Street." At the time, some 1,600 people lived in the area.

The project was rooted in the idea that if you cleared out cities' bars, cheap hotels and homeless missions, you could attract a new wave of capital.

The federal government was pretty much handing out money to cities that did this. Often, they used the power of eminent domain to forcibly purchase land that would be cleared out and resold to private developers. In a way, it was a heavy-handed effort to repair the damage that decades of white flight and suburbanization had inflicted.

Of course, it also was in fact the demolition of poor communities.

In essence, Denver and other cities "corrected the blight of poverty by eliminating the poor, driving them into other neighborhoods or public housing," as Richard White wrote in "It's Your Misfortune and None of My Own: A New History of the American West."

Robert Cameron, the head of the Denver Urban Renewal Agency, said that the "slum clearance" was justified because "substandard areas breed social and economic ills of the worst kind," and that "most of [the displaced people] are skid row types," as Owen Gutfreund noted in "20th-Century Sprawl: Highways and the Reshaping of the American Landscape."

So, using millions of federal dollars, DURA bought the property in the "Skyline" area, relocated the residents (often to new housing projects in outlying areas), demolished the buildings and remediated any contamination.

Only a transformative effort by Dana Crawford saved the historic buildings of Larimer Square, as detailed in the Colorado Encyclopedia. A few other structures, including the tower, survived as well. For a detailed accounting of what was lost, I refer you to Denver Infill.

"Many valuable buildings were, of course, lost," according to John Olson, preservation director for Historic Denver. "Most of these were 2-5 story historic commercial, office, and hotel buildings, but there were some even larger."

And what would replace them?

At one point, the city considered driving a partially underground "Skyline Freeway," through the renewal area, Olson said.

That plan never came to be. Instead, the demolished areas were largely left as blank parking lots, as private developers didn't immediately have the means and motivation to rebuild in the demolition area.

"The result was a huge hole in the heart of Denver," White wrote.

That vacuum would be filled over the next decades with the "Tabor Center, Writer Square, various shiny office towers and surface parking lots," as Infill put it. But it'd be some time before any real residential or retail life returned to the area.

"In effect, Downtown Denver conceded retail business to the suburban shopping malls, for the time being, and instead developed new office buildings," Gutfreund wrote.

This period of rebuilding also brought the 16th Street Mall. To continue following the thread, head over to our interview with the Mall's designer about his original intentions for the area.

Have thoughts on how Skyline ultimately affected Denver? Email me. I'll publish the most thoughtful comments if I get enough.

Thanks to r/Denver user ambirch for surfacing the 1976 image and to The Nick DeWolf Foundation for allowing republication. DeWolf, of Aspen, died in 2006.