On Saturday, the Denver Art Museum opened a new special exhibit, "The Western," that examines America's classic, controversial genre through more than 100 years of iteration.

Most striking about the presentation is how century-old artworks seem not at all old.

Instead, the familiar tropes and images that make the Western so recognizable seem to maintain an iconic quality. From a 19th-century Remington painting all the way to Tarantino's "Hateful Eight," the genre's consistencies and evolutions are all captured within the museum's artfully-crafted tour through time.

A genre is, by definition, a configuration of tropes and rules that are repeated over and over. It's not just the tale of the lonesome cowboy, but a set of visual cues like gaping doorways and expansive views of Monument Valley that the Western has been built upon.

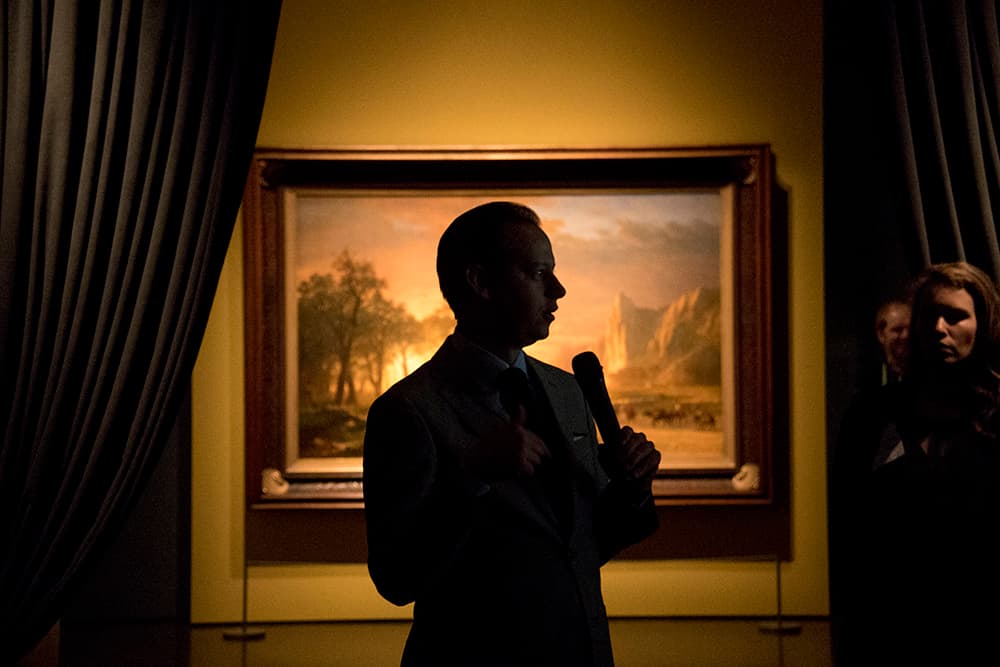

But while many people picture John Wayne when they think of the Western, the Museum's exhibit makes clear that the genre was born before the age of American movie making. Those familiar images utilized by Western movie makers, said exhibit co-curator and Denver Art Museum Director Thomas Brent Smith, were first taken from paintings and sculptures.

"If you were an early filmmaker in America," he said, "where would you go for aesthetic inspiration?"

Through time and media, those familiar tropes have been reiterated again and again. With that repetition two things begin to happen: First, the images become universally recognizable, but second, they begin to change. As American culture shifts, so does the relevance of familiar symbols like a lawman on horseback. The genre's evolution becomes a reflection of American culture at large.

This is perhaps most significant in the portrayal of Native Americans and people of color in general throughout time. A genre that once celebrated glorious victory in the Indian Wars could not still be relevant today without some inward reflection.

As the exhibit moves into the post-WWII era, said co-curator Mary-Dailey Desmarais, it shows how Western stories begin to look more critically at themselves. Women, she said, begin to take on more important roles and portrayals of Native Americans become more sympathetic. Visions of law enforcement and justice become murky and more complicated.

This convolution comes to a head as the exhibit enters the counterculture period, where Easy Rider puts a cowboy on a motorcycle and Andy Warhol presents cowboys in homoerotic contexts. Blazing Saddles pokes fun at the genre's history of racism and The Wild Bunch, an extremely violent film by Sam Peckinpah, lends commentary on the Vietnam War.

Seeing the Western in full spectrum across a century gives viewers an "a-ha!" moment. It demonstrates how the genre belongs to artists of all perspectives and, by playing off of familiar imagery and tropes, how tales of men and women on the Western Frontier have come to represent so much of the American experience.

“It’s not only about the history of the American West," Desmarais said. "It’s about the history of who we are as people, for the good and for the bad.”