Cuts to Medicaid in the Better Care Reconciliation Act -- the Senate version of the House's American Health Care Act -- could cost Colorado as much as $15 billion over the next 10 years. That's if the state wants to keep covering the more than 450,000 people who got insurance through the Medicaid expansion -- and it might not be able to.

This analysis comes from the nonpartisan Colorado Health Institute in response to a "discussion draft" of the bill released Thursday, the first time anyone outside a small group of Republican senators saw the bill which is scheduled for a vote next week. Even U.S. Sen. Cory Gardner had not seen the bill on Wednesday, despite being part of a working group on health care policy, and on Thursday, he said he was still reading it to develop his position.

The Colorado Health Institute estimates that as many as 628,000 Coloradans could lose Medicaid coverage by 2030.

That impact will be felt most strongly in rural areas and could force state legislators to grapple with agonizing choices, according to the Colorado Fiscal Institute. That group released an analysis Thursday of the House version of the bill, most of which also applies to the Senate version. A lot more people in rural areas rely on Medicaid than in urban areas, so they face the brunt of cuts there, with ripple effects for hospitals and local economies. Urban areas, as well as Aspen and Vail, have more wealthy people, so they'll get most of the benefit from the tax cuts also included in the bill.

Thamanna Vasan, an economic policy analyst with the institute, said those broad findings hold true for both versions of the bill, though the subsidy structure of the Senate bill is different.

"The general size of the impact and the way it will hurt communities are very similar," she said.

Joe Hanel of the Colorado Health Institute said the impact of the Medicaid cuts is actually worse in the Senate version of the bill, at least for Colorado. Initial coverage of the Senate version of the bill focused on the longer timeline for phasing out the Medicaid expansion, when compared to the House bill. However, the reduction in funding for people covered under the expansion is greater, and it also makes long-term changes to Medicaid that will leave states with less money to pay for care.

The total fiscal impact is worse, Hanel said: $14 billion over 10 years for the House version, $15 billion for the Senate version, just in loss of federal funding for Medicaid.

The Medicaid expansion has played a big role in more Coloradans getting health insurance.

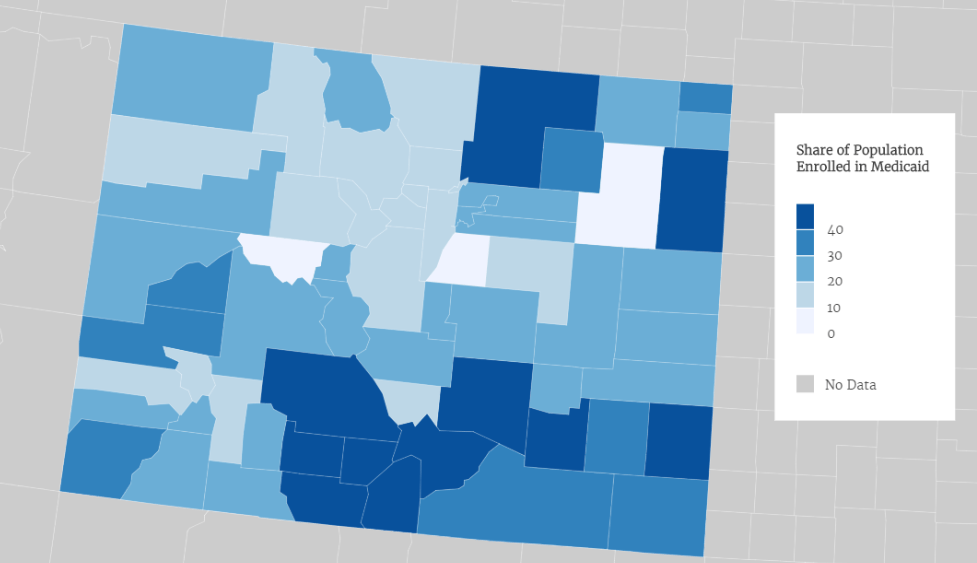

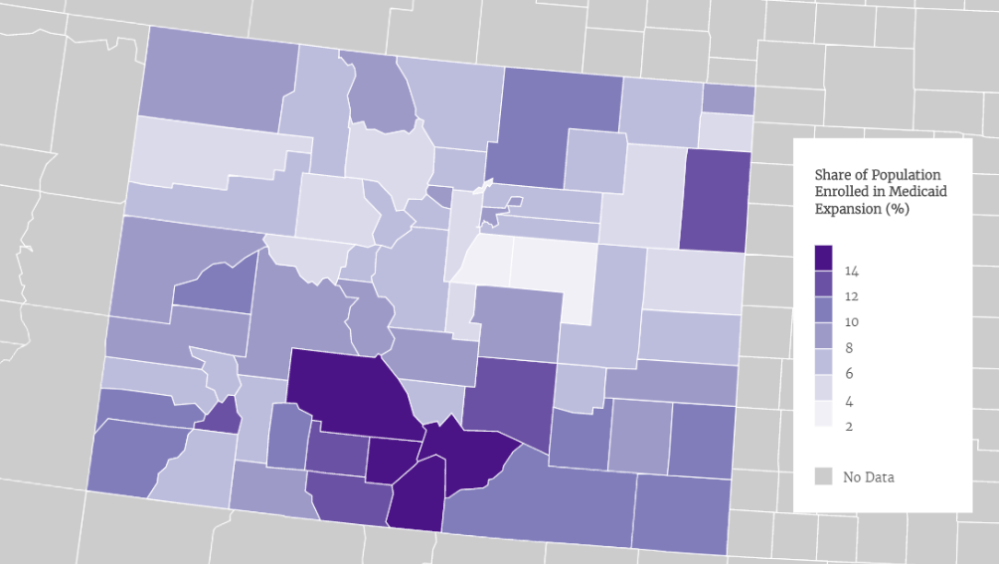

Roughly a quarter of all Coloradans use Medicaid. In rural Costilla County, its 54 percent, and in Pueblo, it's 41 percent. This is a group that includes the poor but also pregnant women, children with disabilities and seniors who need long-term care. Obamacare raised the income threshold for Medicaid so that a lot more people qualified, with the federal government picking up the vast majority of the cost. About 450,000 Coloradans have Medicaid coverage specifically because of the expansion.

The Better Care Reconciliation Act begins to reduce what the federal government pays toward the expansion, starting in 2021. By 2024, it would be the same 50 percent share at which it covers the core Medicaid population.

"Colorado would not be able to pay for half the cost of the expansion," Hanel said. "The legislature would just reach a breaking point where they are not able to afford the state's required matching funds, and they would have to repeal it. The idea that this bill goes easier on Medicaid, we are just not seeing it."

The Colorado Fiscal Institute looked at the total Medicaid population and expansion population by county, and the reliance of rural Coloradans on Medicaid in general and the expansion in particular is clear.

The Senate bill also proposes to change Medicaid to a per-capita cap. That means states would get a set amount of money per enrollee, instead of the state and federal government sharing the cost of medical care for all enrollees, whatever that number ends up being each year. Theoretically, this approach -- similar to block grants -- would allow states to experiment with different approaches that would save money over time and allow them to provide the same or better care for less money.

But Hanel said Colorado is already experimenting under current law. The projected savings are much, much less than the proposed loss of funding. The per-capita cap would increase each year in accordance with a medical cost inflation index, but actual medical costs have been increasing at a faster rate than the index.

"The savings we are seeing out of that is not in the ballpark of what it would take to paper over these cuts," he said. "It's in the tens of millions of dollars" while the loss of funding could be closer to $1 billion a year.

The bill also includes tax cuts that benefit wealthy people, who mostly live in urban counties on the Front Range.

Employing software that is widely used to study economic impact, the Fiscal Institute found that only six counties saw a net benefit from the House version of the bill: Douglas, Boulder, El Paso, Broomfield, Eagle (Vail) and Pitkin (Aspen).

"This is in great part due to the repeal of ACA provisions that would redirect money to wealthy households, especially those where individuals make $200,000 or more," the report said.

The predicted impact extends well beyond those who would lose coverage. Hospitals and clinics are major employers in some rural communities, and these hospitals are bracing for a major financial hit if their patients lose coverage. So there are likely to be job losses and a ripple effect through those local economies, the institute said.

Colorado's rural hospitals just fended off an existential threat, and now they face another.

One of the issues that dominated this past legislative session was the hospital provider fee, which the state collects on patient revenue so that it can be matched by federal dollars and returned to hospitals based on their Medicaid patient load. Rural hospitals have become particularly dependent on this fee, and peculiarities of the Colorado budget process meant they were facing serious cuts -- so serious that some hospitals were likely to close. A major piece of compromise legislation saved the day. The issue was considered so dire that a number of Republican legislators let go of long-held fiscal principles and their fear of a primary challenge to vote yes.

Vasan said the proposed Medicaid cuts put rural hospitals "back on the cliff's edge."

In a statement, the Colorado Hospital Association said the Senate version of the bill would put care at risk.

“Unfortunately, the draft bill released today by Senate leadership threatens to move Colorado in the wrong direction, especially for our most vulnerable patients,” said Steven J. Summer, president and CEO of the association. “The proposal could cause deep cuts to Medicaid that covers thousands of Coloradans, including those with disabilities and many children. It will be particularly harmful to rural Colorado communities. We strongly urge Senators Bennet and Gardner to continue working on this proposal to develop legislation that will move Colorado forward -- instead of setting us back -- and will protect coverage for Coloradans.”

Hanel said uncompensated care could become a major problem again.

"All the consternation over rural hospitals and the victory they won through the hospital provider fee, well, now they have another problem on their hands," he said. "Rural hospitals are disproportionately dependent on the Medicaid expansion. Before they had a lot of non-paying customers. It has been, in some cases, a life-saver for rural hospitals. Now they might go back to having a lot of non-paying customers, and it might be worse than it was before."

The bill got the endorsement of one of the top health policy wonks on the right.

Writing for Forbes, Roy argued after the passage of the Affordable Health Care Act that the House version of the bill got the tax credit structure wrong. Millions of people would lose coverage through Medicaid but not get enough of a subsidy to buy individual coverage. Roy said Thursday that the income-based approach to the subsidy was the right one.

One of the big questions is how the bill will affect the individual market.

Conservative analysts like Roy believe regulatory changes in both versions of the bill will make insurance more affordable and give people more options. That's been one of the big complaints about Obamacare in general, and rural counties in Colorado have seen insurers pull out, leaving them with few choices. Premiums have gone up, and many policies have very high deductibles, meaning people pay a lot out of pocket if they actually use their health insurance.

States would be allowed to apply for waivers to Obamacare requirements that all insurance policies cover "essential health benefits." The idea here is that people could buy more basic policies that don't cover, say, mental health care or maternity care, and pay less. In turn, that might induce more young, healthy people to buy policies. Hanel said Colorado is very unlikely to apply for such a waiver because the state has a long and bipartisan record of requiring insurance companies to cover the range of health needs people have.

Many analysts are less confident this bill would help bring down premiums for most people. The bill gets rid of the mandate that people buy insurance but keeps the requirement that insurance companies cover people with pre-existing conditions, some of whom have expensive, chronic medical issues. Hanel said there are some provisions that could help stabilize prices for health insurance but others that could cause additional instability. He thinks it's difficult to model all the impacts on the individual market right now.

In addition, fewer people will qualify for subsidies, and those subsidies will be smaller than under current law.

The Affordable Care Act provides financial help to low- and middle-income Americans who purchase their own health coverage. It provides subsidies to people who earn less than 400 percent of the federal poverty line ($47,550 for an individual or $97,200 for a family of four) and gives the most generous help to people who earn the least.

For example: People who earn $17,000 are only expected to spend 3 percent of their income on premiums for a midlevel insurance plan — the government will kick in the rest. People who earn $40,000, however, are expected to spend 9.66 percent of their income on those monthly payments.

The Senate bill would overhaul these tax credits. It would make fewer people eligible for the help, limiting the subsidies to people who earn less than 350 percent of the poverty line ($41,580 for individuals and $85,050 for a family of four).

Hanel said the subsidies in the Senate version are an improvement over the House version in that they're tied to income and the cost of insurance in your area, whereas the House version was tied just to age. So a person in Grand Junction, where policies cost more, would get a higher subsidy than someone in Denver.

However, fewer people would get the subsidies, those who did would get less money than they do now and they could only be used on the lower-quality "bronze" plans.

Nothing in the bill really addresses the cost of care.

"The biggest thing contributing to rising premium costs is the high cost of care and people's health, which is not very good," Hanel said. "This is still a coverage bill. It's arguing about who picks up the check, not why dinner is so expensive."

So the upshot that is that Colorado could have to choose between covering fewer people and finding a way to come up with a lot more money for health care.

"That is a question of priorities for legislators," Vasan said. "And it will put legislators in a position of having to either fund it fully and cut other services like schools and roads or cutting the expansion or abandoning it entirely. It depends on who you ask, but that is a position that legislators would be put in."

It's a policy question and a political question.

"How is Colorado going to respond to these very heavy Medicaid cuts?" Hanel asked. "It's probably going to be something that could even define the next governor's term. It's billions of dollars that we're talking about, and it's going to be very difficult for the legislature and the new governor to figure this out. We'll be looking at what this does to the uninsured rates and what that does to the health of Coloradans."

This story has been updated with additional information.