Jefferson County's elected officials talked and listened for roughly six hours on Tuesday before deciding to accept a $1.7 million grant for affordable housing and other programs.

This type of decision usually is a simple one. This year, it became an argument that drew the mayors of Lakewood, Wheat Ridge, Westminster, Golden and Edgewater, among many others, to the county headquarters on Tuesday morning.

It was the conclusion of a debate that has been brewing for months in the halls of county government. It was, at its simplest, a fight about whether Denver's large suburban neighbor would break away from a long-running federal effort to make housing more fair and accessible for people with disabilities, racial minorities and others.

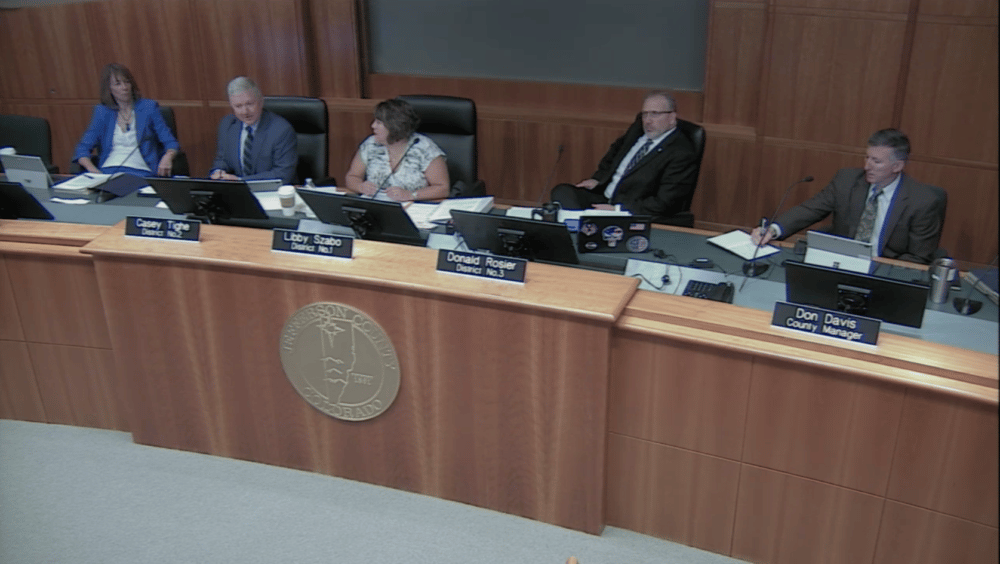

The county's three commissioners ultimately voted unanimously to accept the federal money, with the requirement that the county will reassess the program and potentially try to wean itself off federal support in the years ahead.

A group of conservative activists -- the AFFH.net Opposition Group -- has sown skepticism of the federal housing program among Denver's outlying communities, warning of a supposed federal plan to force the creation of "low-income, racially diverse, high-density housing.” That free money isn't so free, they argue.

Last year, Douglas County turned away hundreds of thousands of dollars from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development on similar fears. Making the same decision in Jefferson County could have caused chaos for private projects, including hundreds of potential new low-income units.

"Without it, the project doesn’t work," said developer George Thorn. The $1.7 million in question is just a fraction of a typical development project's cost, but Mayor Herb Atchison of Westminster described the money as crucial for the "last mile" to complete projects.

The county's population is nearly as large as Denver's. It's far less urban, but the completion of commuter rail to Wheat Ridge and Arvada is changing that -- and the continuing shift of poverty to suburban areas is bringing the housing crisis to Jefferson County regardless.

Justin Ball, who bought his home in Lakewood with the help of previous federal money, warned that quitting the program would have ripple effects.

"In my opinion, a lack of suitable housing for those less fortunate will slowly but surely become everyone’s problem -- a problem that can and will bring down entire communities," he said, his young son by his side. "Today, I’m proud to say that I rely on zero public assistance."

Donna King, an Arvada resident in her 80s, said that she desperately needed Section 8 or entrance to a new affordable community, both of which can be funded through the Community Development Block Grants (CDBG) in question. The federal HOME program also was up for debate.

"I am now paying over half of my income for my rental," King said. She concluded her comments on a sarcastic note: "Welcome to Colorado -- no vacancy."

AFFH.net Opposition Group has focused on a new rule -- which won't be in effect for Jeffco until 2020 - that will require the county to compile publicly available data into reports on segregation and other barriers to the goals of the Fair Housing Act, which protects a wide range of groups from discrimination in housing.

Kim Monson, a former Lone Tree councilwoman, said that federal funding “facilitates social engineering of our neighborhoods” and "picks winners and losers." She previously voted no to accepting HUD funding in Lone Tree.

"In the old days, people helped people," she said. She also argued that she was representing thousands of people who wouldn't want to be burdened by funding the program and increasing the national debt.

One of the HUD opponents' stated fears is that by participating, the county will make itself an easier target for federal and third-party efforts to enforce that long-standing law. (The counter-argument is that the new program will allow for more uniform comparisons across communities and identify problems early.)

"He who controls the statistics controls the debate," said Dee Oltmans of Evergreen. "If you let God and the faith and the church come back in, they will take care of the poor and the homeless."

Others critiqued the program as wasteful, but Jeffco staff said they kept administrative costs under 20 percent of the federal program.

Here's how elected officials reacted:

Commissioner Casey Tighe, a Democrat, voted to keep the funding.

"This is a great day. A lot of times, we don’t have anyone at our hearing. What I heard today is I heard people care about our community," he said.

Commissioner Libby Szabo, a Republican perceived as a swing vote, asked whether the money wouldn't simply go elsewhere if Jeffco rejected it. And she said that the county is strictly limited in its spending and by "unfunded mandates."

"We can't keep up," she told Monson. She also noted that she expected the Trump administration would respect local control, and she confirmed that nothing had actually changed yet about the program. She called for the county to create a plan by 2020 to "wean" itself off federal support for affordable housing.

Commissioner Donald Rosier was the most openly skeptical, asking why money often goes to non-housing purposes, such as a streetscape project in Lakewood's "40 West" area of West Colfax.

"What I saw was those dollars being used for anything but housing," he said, later saying he was "appalled" that not all the funds were used for housing and assistance. In fiscal year 2014, for example, about $271,518 went for public improvements.

Mayor Adam Paul of Lakewood responded that those projects benefitted blighted areas of town where poverty is concentrated. "It’s a community that’s in need of some love and care, I would say," he said. He added that the spending could also attract market-rate housing.

Paul framed the money as a way to prepare for change "as Denver’s continued to gentrify and continued to push some of their issues into our county."

That comment got on the central tension of the argument: Denver's neighbors know change is coming. Often, they share an instinct to keep things the same. Golden, for example, has developed a culture that wants to stay small, according to Mayor Marjorie Sloan.

The question is whether that's possible.

"Congestion is increased," Sloan said, "by having people that live outside the community and drive to work."