On Thursday an exhibit on Gabriel Figueroa, perhaps Mexico's most famous cinematographer, opens at the McNichols building as the Biennial of the Americas also begins.

While "Under the Mexican Sky: Gabriel Figueroa, Art and Film” is a traveling show, its display in conjunction with the Biennial emphasizes how the Mexican and American "golden ages" of cinema were intertwined. It's an apt artistic venture for those interested in the Biennial's mission to show how culture and economics in the western hemisphere may be inseparable.

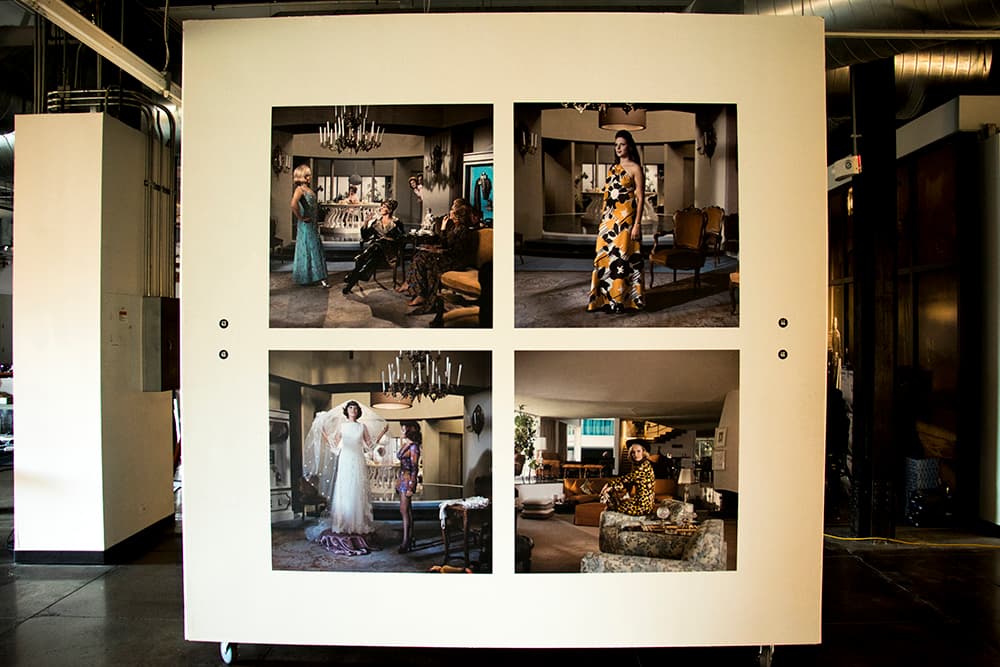

Through December 23, on the third floor of the McNichols building, towering movie projections and enlarged frames from Figueroa's work transform the space into a cathedral of imagery. A young Clint Eastwood rests a hand on his holster, a man with arms outstretched stands atop a tower surrounded by an endless desert, Dia de los Muertos skeleton puppets dance beneath hanging strings. Upon entering, audiences are awash with sights and sounds.

As he worked on Tuesday night to ready the exhibit, co-curator Alfonso Morales said these images and symbols not only spurred a golden age in Mexican cinema, they also contributed to the creation of modern Mexican identity through film.

With 50 years of Figueroa's work under one roof, he said, the exhibition is a "compendium of the Mexican history of cinema.”

His career began during an explosion of filmmaking in Mexico that was due, in part, to the United States' involvement in World War II. As American filmmaking took a backseat to the war effort, the creative void left by Hollywood's absence gave Mexican artists a chance to flood the hemisphere with new work.

Figueroa's style, in turn, was informed by Hollywood's own golden era. He spent some time working for American filmmakers as he learned the craft, most notably becoming the apprentice of Gregg Toland, a favorite of Orson Welles who worked on the legendary "Citizen Kane." Figueroa, Morales said, brought Hollywood ideas back home and imbued them with Mexican heritage to create what the curator calls a “new movement in cinema."

As the two countries' cinematic legacies grew, Figueroa was called upon to shoot his home country for American directors and actors including Eastwood in "Two Mules for Sister Sarah" and Henry Fonda in "The Fugitive."

His career would stretch into surrealism and pop art, bring him to work with equally important directors and generate numerous awards, including an Oscar nomination. "Los Olvidados," or "The Young and the Damned," would be the second film ever recognized by UNESCO as a "Memory of the World."

If you like movies or photography, this free exhibit is a feast for the eyes and well worth a visit. If you're interested in the Biennial of the Americas, there's lots to appreciate in that Figueroa's work touched cinematic development on both sides of the border.

And Alfonso Morales agrees. Filmmaking is an “international language,” he said. "There are no borders in cinema.”

The Biennial was created to "recognize and build upon the important economic and cultural ties in the Americas," according to its website.