The Harm Reduction Action Center on Colfax Avenue already offers people who use injectable drugs a place to exchange dirty needles for clean ones. This is an idea that was once controversial -- and remains so in some quarters -- but is now widely accepted as reducing the spread of bloodborne diseases like HIV and hepatitis without increasing the use of intravenous drugs.

Executive Director Lisa Raville hopes that the same public health approach to the problem of opiate addiction will allow the center to become a supervised injection site, a place where people can use drugs like heroin under the watchful eye of trained professionals who can respond to an overdose and make sure they stay safe until the day they're ready to make a change.

"What we're in the midst of is an overdose epidemic not only in the United States but in the state of Colorado," she said. "It's very counterintuitive but once you explain it to people, it makes sense. ... This is the time we have to try. If it just saves one life, it's worth it."

For this to happen, either at the Harm Reduction Action Center or at a new facility operated by a nonprofit or public health authorities, first the Colorado General Assembly and then the Denver City Council will need to sign off on the idea. Earlier this week, a package of opioid-related bills that includes authorization for a pilot program in Denver passed out of an interim legislative committee with bipartisan support. Council President Albus Brooks also supports the idea, and he's leading a trip to Vancouver to observe supervised injection facilities in that city.

But Mayor Michael Hancock has declined to weigh in on the idea so far, and securing approval for both the idea and for the actual location is likely to be contentious. San Francisco and Seattle are in the planning stages for their own supervised injection sites, but no city in the U.S. has yet opened such a facility. In King County, home of Seattle, opponents of public consumption sites gathered enough signatures to place a ban on the ballot, but a judge recently knocked down the initiative as infringing on the power of public health authorities. The sites remain illegal under federal law, and a White House commission on the opioid crisis did not recommend changing that.

Brooks has a personal reason for supporting supervised injection sites.

As CBS4 first reported in August, Brooks said he got hooked on opiates while recovering from cancer surgery last year.

“I had cancer and a 15 pound tumor was removed last year,” Brooks told a crowd of roughly 100 people at the downtown Denver Library on Tuesday. “In the hospital they give you some crazy drugs and I got hooked on opioids.”

Brooks said he had strong medical support from his doctors to “figure out how to get off them,” but realizes not everyone has that support.

“We are all affected by this,” he said. “It’s not just people on the streets, it’s everybody. So we need to do something now.”

State Rep. Leslie Herod, a Denver Democrat, is pushing for legislation that would allow local communities to engage in a variety of harm reduction initiatives that might otherwise violate state law. She's been friends with Brooks since college, and she said she was "struck" by his experience. Her sister has also struggled with drug addiction.

"It really does affect everyone," she said. "So many people think they are safe, and it really only takes a few steps."

Herod said she was gratified to see the package of opioid bills move forward and to see a pilot program included. She's hoping to revise the language during the 2018 legislative session to allow for a broader range of harm reduction strategies. As a senior policy advisor on human services issues to former Gov. Bill Ritter, Herod worked on Colorado's needle exchange law, and she now regrets that it wasn't written more broadly. If the legislature had created a broad allowance for local harm reduction initiatives instead of a specific exemption for needle exchanges, new legislation might not be necessary now.

"Whatever the local government feels they need to do, the state should not be hindering it," she said. At the same time, "whatever works in Denver is not going to be what works somewhere else. If communities think have the capacity to do this, they'll do it, and if not, they won't."

Raville said the big push right now really is safe injection facilities.

Downtown business owners and service providers like homeless shelters are tired, she said, of serving as "bathroom monitors." Supervised injection sites provide the people who use drugs a safe place to inject, and they also take the pressure off the rest of the community that has to deal with the aftermath. Supervised injection sites can also offer referrals to treatment and support for those who want to try to stop using.

"It keeps people who are homeless from publicly injecting outside in a park or an alley or a business bathroom," she said. "It's been proven to work in so many other cities. Just because it's international doesn't make it any less valid."

Raville thinks the Harm Reduction Action Center is the logical place for such a facility in Denver because people who are addicted to drugs already know and trust them, because they're already regulated by the health department and because they already have a robust good neighbor agreement. People don't buy and sell drugs in the immediate vicinity of the center, Raville said, because clients understand they need to "protect the space. ... We know if we get kicked out, we'll have nowhere to go. People know it's the one safe spot where they can talk about their drug use."

"We know our neighborhood, we know our neighbors, we know our participants," Raville said. "We know being a good neighbor."

Bob McDonald, Denver's public health administrator, hasn't taken a position yet on supervised injection facilities, but the Department of Environmental Health is researching how they work in other cities and the pros and cons of various models.

The issue is an urgent one, but that doesn't mean the city should rush, McDonald said.

"If this is something that comes to Denver, we want to make sure that it's done right," he said.

Among the questions Denver will be asking: Should it be run by the government or a non-profit? What types of rules should be implemented to provide some structure? What would funding streams look like? What would success look like? What metrics will we use to measure success? How will we know if we're achieving our goals?

Earlier this year CBS4's Brian Maass visited Vancouver, a city that has been rocked by opioid addiction and overdose deaths. Vancouver operates several safe injection sites, and addicts and the people who work with them credit the facilities with saving lives.

In his report, both the potential and the limitations of these sites are clear. The medical professionals who oversee one facility say they reverse 10 to 20 overdoses each week. Every one of these is someone who might have died if they'd overdosed in an alley, and eventually, some of them will decide they're ready for a change and stop using drugs.

“I don’t want to die,” one addict named Kayla told the CBS4 team. She had previously overdosed in an alley where “sometimes people don’t get found.”

But Maass also visited alleys where people continue to shoot up in public in large numbers, despite the presence of supervised injection facilities, and Vancouver saw more than 1,000 overdose deaths last year and is on pace to surpass that in 2017. Supervised injection facilities are not a magical cure-all.

For years, Canada had just a single supervised injection site, but the Liberal government of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has overseen a major expansion of the program, with 21 new sites approved in the last two years. As the CBC noted in a recent analysis, the idea has gained much more acceptance, and even critics now tend to frame their objections in terms of making sure the sites are good neighbors, rather than dismissing the idea entirely.

Colorado has not been as hard hit by opioid addiction as other parts of the country -- yet.

Colorado currently falls below the national average for drug overdose deaths, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control, and the region lags behind the Midwest and Northeast for heroin overdose deaths and the South for prescription opiate overdose deaths.

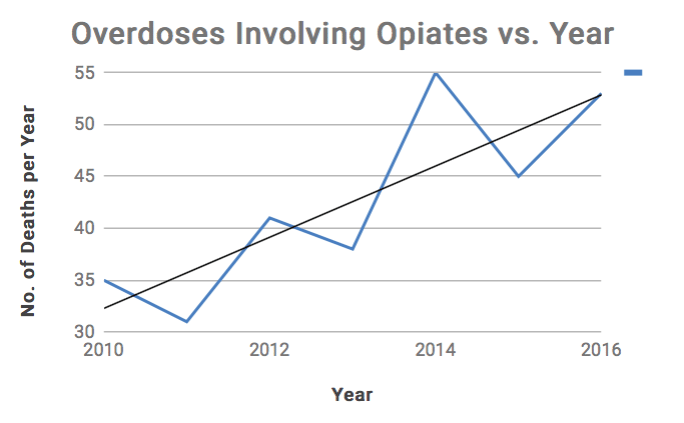

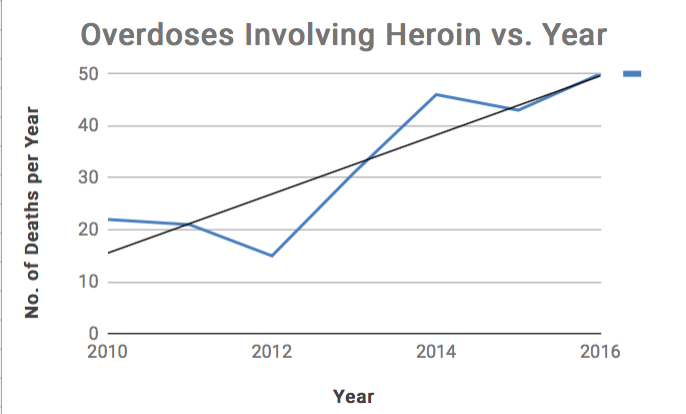

Nonetheless, deaths from heroin overdoses seem to be on the rise. Colorado saw a 23 percent increase in heroin overdose deaths in 2016, even as total opiate overdoses deaths declined 6 percent, perhaps reflecting new controls on prescription painkillers. In Denver, the Office of the Medical Examiner recorded 103 opiate overdose deaths in 2016, 50 of which were from heroin. In 2010, just 57 people died from opiate overdoses, and heroin accounted for 22 of those.

At the same time, overdose deaths for all drugs aren't following any particular pattern and have been lower in recent years than in 2008 and 2009. Medical Examiner Steve Castro said his office doesn't currently have the capacity to do detailed analyses of overdose trends, but he's hoping a new software system will change that.

Herod said the state and local authorities have an obligation to react before things get worse.

"We have an opportunity to get ahead of this, and not only do we have an opportunity, we have a responsibility to get ahead of it," she said. "I do not want Denver to be a poster child for what happens if you do not address addiction."

Correction: This article has been updated to correct the number of deaths from opiates in general and heroin specifically.