Forest City, the master developer of the Stapleton community, recently made a change, quietly and without fanfare. The company took down the word "Stapleton" from the signage around the shopping center at East 29th Avenue and Quebec Street. Now it's just E. 29th Avenue Town Center.

In an interview, Forest City Stapleton Vice President Tom Gleason downplayed the significance of the change and cast it as part of a natural evolution.

"As the town center became more established, we felt it didn't need the name," he said.

For some people, Stapleton has never been just a name, but any movement to formally change the name of the community that's been built on the site of Denver's old municipal airport -- an airport that was named after the mayor who helped develop it, who was a member of the Ku Klux Klan and installed Klan members throughout city government -- has proceeded in fits and starts.

This time feels like it might be different, as national events focus our attention on the importance of symbols and monuments and the question of how we reckon with our history. But not everyone is on board. For plenty of Stapleton residents, the first thing the name evokes isn't Denver's Klan mayor but the warmth of community they've known here.

On Monday, Nita Mosby Tyler of the Equity Project will facilitate a series of conversations about the idea of changing the name of Stapleton. Tyler is an expert on facilitating difficult conversations around race and diversity, and the purpose of the meetings, one from 1:30 to 3:30 p.m. and the other from 5:30 to 7:30 p.m., is to hear from people on all sides of the debate.

"I've been the person who has cut conversations short as our meetings are held in a public space and we need to vacate to respect their operating hours," Amanda Allshouse, president of SUN, wrote in an email. "Ensuring an adequate opportunity for people to voice their experiences or opinions on this issue is important and has been lacking. People have had more to share, and thus we have more to learn."

These conversations will inform the next steps, but they won't determine it. There is no set process to change a neighborhood's name, which means everyone is feeling their way. Members of Rename St*pleton for All want to start with the name of the registered neighborhood organization, Stapleton United Neighbors (SUN) and with the branding that Forest City and the Stapleton Master Community Association use for the community. That's why the signage around the town center is about more than just a logo.

"Changing the name is more symbolic than substantive," said Gregory Diggs, a leader in Rename St*pleton. "My personal position is that there's a lot of more meaningful work that needs to be done on housing and programming and relationships and education than changing the name. But if people don't want to change the name, how can that more substantive work be done?"

What was Benjamin Stapleton's connection to the Klan?

Stapleton served as mayor of Denver from 1923 to 1931 and again from 1935 to 1947. There were rumors of his membership in the Klan during his first run for office, but he also maintained good ties with Denver's black, Jewish and Italian communities and did not give any outward sign of racial prejudice.

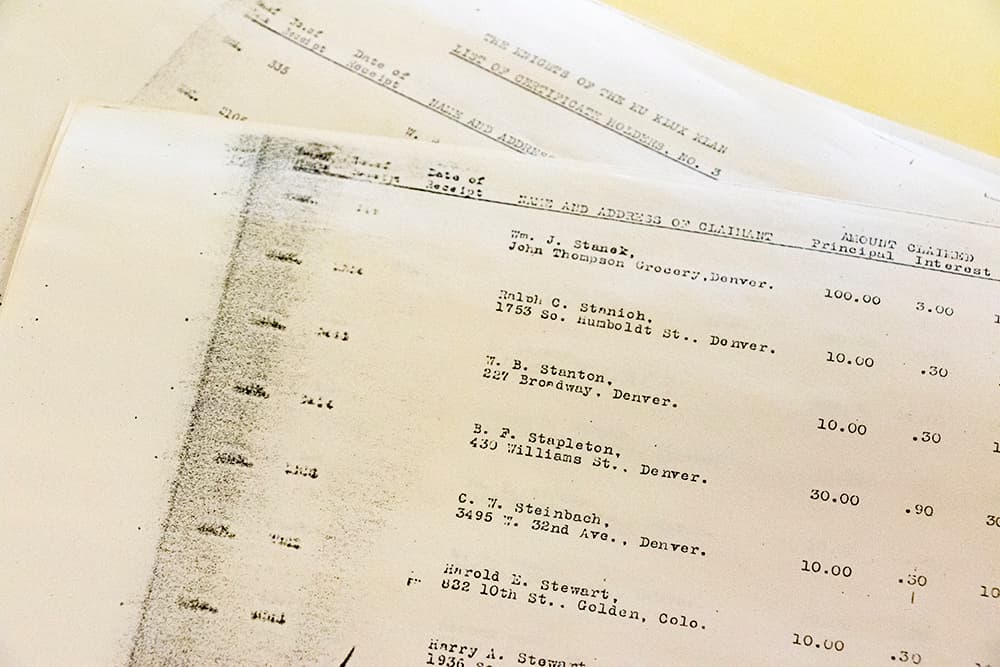

Under pressure from his liberal backers, he made a public statement that condemned "secret organizations." "True Americanism needs no mask or disguise," he said. But he refused to condemn the Klan by name, and the organization's roster listed him as member 1,128. After Stapleton's election, a hooded Klansman appeared on the steps of city hall, and his administration was praised in the national Klan newspaper. Stapleton appointed Klan members to key roles in city government, particularly in the police department.

The picture of Stapleton that emerges in Phil Goodstein's In the Shadow of the Klan: When the KKK Ruled Denver is of a man deeply attuned to the political moment and easily swayed by the more forceful personalities around him. As his allegiance to the Klan became clearer and as his political appointees increasingly bungled the basic work of governing the city, former supporters launched a recall campaign. Some of the people working on the recall were also Klan members, though, likely an attempt to reiterate to Stapleton that just as they helped make him, they could also break him.

During the recall campaign, Stapleton appeared at a Klan rally on Tabletop Mountain in Golden and told the assembled crowd, "I will work with the Klan and for the Klan in the coming election, heart and soul. And if I am re-elected, I shall give the Klan the kind of administration it wants." This is according to a contemporary newspaper account reprinted in Goodstein's book. Stapleton prevailed in the recall; that same year, a Klan candidate won the governorship and Klan candidates took many seats in the state legislature.

Many people condemned and fought against the Klan at the time, but the organization's members included men and women at the highest levels of society. Klan leaders the Senters, whose archives now belong to the Denver Public Library, were also known for their enormous and elaborately decorated Christmas tree and for opening their home to neighborhood children each holiday season. Klanswoman Minnie Love was a founder of Children's Hospital and active in a range of reform causes, from women's suffrage to ending child labor, as well as being an advocate of eugenics.

Many organizations simply remained silent rather than take on the Klan, and the Klan allied itself at various times with labor organizations, with good-government reformers, with the Chamber of Commerce, with Prohibitionists and so on. At a recent panel discussion on the role of the KKK, Goodstein described the downfall of the Klan coming not from widespread rejection of its racist message but from frustration with corruption and incompetence.

From their perch inside the vice squad, Klan police officers had gotten deeply enmeshed in illegal activities. Stapleton, in contrast, was a puritan who hated drinking, ordered the police to crack down on jaywalkers and once, when he was a judge, fined a woman for showing eight inches of leg as she stepped into a street car.

Stapleton eventually grew tired of the Klan's efforts to control his administration and teamed up with federal Prohibition agents and Catholic members of the police department to stage a series of raids on speakeasies, brothels and gambling dens. Numerous Klan members were caught up in the raids, though the primary targets were Greek, Italian and black-owned institutions. Their exposure conflicted with their public image as upholders of morality and virtue.

The change was not immediate but gradual. Stapleton distanced himself from the Klan -- in 1925, he welcomed the NAACP convention to town -- and the Klan itself was riven with internal divisions. In 1926, the Minute Men, an organization that spun off from the Klan, launched another recall attempt against Stapleton, this time seeking to eliminate the office of mayor and replace it with a city manager form of government. The city attorney who fought the recall effort on Stapleton's behalf was a Klan member.

Gradually it became embarrassing to have ever been part of the Klan, and the organization simply faded into the background. But there was never any real accounting for the fact that the Klan had so thoroughly dominated the city. "Their robes gathered dust in the closet -- supposedly the sheets were nothing more than grandpa's old nightgown," Goodstein writes of the decline of the Klan. The Senters continued to display their Christmas tree through the 1960s.

Speaking on the same panel at the Blair-Caldwell African-American Research Library in Five Points, Charlene Porter recalled her parents and grandparents telling stories of the Klan's prominence in Denver. Porter is the author of Boldfaced Lies, a work of historical fiction about the wife of a Klan leader in Denver who learns she is actually one-quarter black. These stories of the Klan seemed so incongruous that as an adult, she sometimes wondered if she had imagined the whole thing, until she started doing research for her book.

It was in that spirit of forgetting that for many years Stapleton was more remembered for his public works projects than his Klan membership. He oversaw the construction of the City and County Building, Red Rocks Amphitheater, the highway that would become I-25 and Denver Municipal Airport, on which ground broke in 1929. It was seen as a boondoggle at the time and contributed to Stapleton's loss in the 1931 municipal election. The airport was renamed in his honor in 1944, while he was serving his fifth and final term as mayor.

Stapleton the airport generated the name of Stapleton the community.

Gleason said that Forest City was always aware of the sensitivity around the name and tried to use it sparingly. For example, the metropolitan district created for the redevelopment project was called the Park Creek Metropolitan District. Gleason said Forest City has always assumed that new neighborhoods would arise within the Stapleton redevelopment site, and those names eventually would take over in public use.

But Forest City was allowed to use the name Stapleton for marketing and as a locator starting in 2002, and it continues to do so to this day.

"If you're going to get major office users to the Central Park Station TOD (transit-oriented development), you need to say Central Park Station at Stapleton," Gleason said. "... We did not name the airport. It's been around for a long time, and we have understood there would be people with very painful associations with that name. We have tried to limit its use."

People who want to change the name see Forest City's current attempts to distance themselves from it as disingenuous. It's hard to imagine that the name would be so widely used today if Forest City had opted for different branding in the early aughts.

Nonetheless, for some people Stapleton no longer refers primarily to the former mayor.

"When I think of the name Stapleton, I think of a community," said Councilman Chris Herndon, who moved to Stapleton in 2008. "When I knocked on my neighbors' doors, I remember their warm embrace. It was welcoming. It's not a name that does anything other than bring up positive memories, in my personal experience."

The Stapletonion, a satirical neighborhood publication, recently published a piece in which the community is left entirely nameless, lest any new name later become associated with hate. The name change movement is a frequent target of the Stapletonion, whose writers clearly don't think much of the arguments against the name.

Librarian and archivist Laura Ruttum Senturia wrote thoughtfully for Denverite on what it means to call a place by a name. "There is a difference between remembering and memorializing," she wrote. "... As a society, we use plaques and statues, and the names of schools, parks, and neighborhoods to honor our past. That there are few memorials to Benedict Arnold should tell us something."

One theme that has emerged in recent months is the idea that people who want to keep the name are afraid to speak out for fear of being labeled racist. That's one reason for the facilitated conversation.

"I believe we're going to create a situation where individuals can express their honest opinion one way or the other without being personally attacked," Herndon said.

Diggs, the leader in the rename movement, also sees value in the facilitated discussion, but he expressed frustration that more consideration is being given to people whose opinions might be considered racist than to people who feel unwelcome in the community. And he wonders just how widespread this fear of speaking out is, since these concerns are always shared anonymously, through third parties.

Diggs, who is black and whose children are mixed-race, was one of the earliest residents of Stapleton, the second person to move into his subdivision and a founding board member of Stapleton United Neighbors.

He remembers when the neighborhood association was named. It made a nice acronym, SUN, that represented the association's purpose, and he wasn't bothered by it at the time.

But over the years, he's felt like people of color aren't always welcome in Stapleton. His children have sometimes felt like outsiders in their own community, he said, and there's been tension as black residents of nearby Montbello and Northeast Park Hill take advantage of the grocery stores, parks, swimming pools and schools built to serve majority-white Stapleton.

Those experiences shape Diggs' opinion on the significance of the name.

A name change "would mean we are willing to work on the more substantive issues of diversity and equity," Diggs said.

Genevieve Swift, also a leader in Rename St*pleton for All, is white, and she sees racism in posts on Next Door in which her neighbors report the presence of "suspicious" black men doing things like "waiting by a tree" with alarming regularity.

"People really need to wake up and see what's going on," she said. "Especially in a neighborhood like Stapleton that is mostly white people with money, you can think you're a nice person and not see what's going on in your own community."

"It's not that people want to honor this Klan member," Swift added. "They think we've reclaimed the name, and we're not racist."

Herndon just doesn't see the same patterns. There have been "instances" of racism, he said, but other instances -- the woman who bought a new coat and socks for a homeless man who lost his coat, the neighbors who organized a GoFundMe to buy tires for residents who had seen theirs slashed -- are more representative.

"The name to me doesn't incite divisiveness," he said. "It represents community."

Black Lives Matter 5280 called for the neighborhood name to change back in 2015, but that effort didn't go far. Diggs said the group was seen as outsiders, even though some members live in Stapleton, and primarily a black organization rather than a community organization.

Events on the other side of the country helped reignite the debate.

A man in Charlottesville, Virginia, ran over counterprotestor Heather Heyer with his car and killed her as white supremacists rallied under the banner "Unite the Right" in August. They were protesting the removal of a Confederate monument there. SUN sent out a letter decrying the events in Charlottesville and stating that Stapleton as a community would not tolerate symbols of hate.

Diggs said the letter struck a sour note for some.

"That's nice, but it was on SUN letterhead with the name Stapleton in it," he said. "And some of us said, you can't say you don't tolerate symbols of hatred when you've got the name Stapleton right there."

Herndon agrees that national events are playing out locally: "It's different this time because of what's going on in the world."

Gleason of Forest City and Herndon both said it should ultimately be up to the community to decide what it wants to be called. A neighborhood association survey earlier this year found a majority of respondents are comfortable with the name. Diggs said community sentiment should play a role in the decision, but issues of justice shouldn't be decided by a simple majority.

"If slavery were put up to a vote, I'd still be a slave," he said.

Keven Burnett, executive director of the Stapleton Master Community Association, the overarching HOA for Stapleton, told residents back in September that a name change could present legal challenges. As reported in Front Porch Stapleton, the name appears on all zoning documents and on all the deeds, title documents and mortgages as part of legal property descriptions. Some 200 businesses have the word Stapleton in their name.

Swift said supporters of a change are trying to raise money to help businesses who want to rebrand, but they have no desire to strike the name Stapleton from deeds and title documents.

"We don't care about what's on our mortgage," she said. "We're not looking to create piles and piles of paperwork."

Activists said a good start would be changing the name of the neighborhood association.

The East Colfax Neighborhood Association recently did just that. For years, residents there had gone by East Montclair, fearful of being tainted by association with the crime-ridden avenue. Now Colfax is in fashion, and residents are embracing the "grit." As with Stapleton, there were also economic considerations, as East Colfax is being targeted for reinvestment.

People would have to decide to take action, though. Diggs urged his neighbors not to fear change.

"Things change all the time," Diggs said. "I'm amazed by it. We didn't always have LoDo. We didn't always have RiNo. We didn't always have Anschutz. And that's okay."

If you go

What: Stapleton Name Change Listening Sessions

Where: The Cube Stapleton, 8371 Northfield Blvd.

When: 1:30 to 3:30 p.m. and 3:30 to 5:30 p.m. Monday, Dec. 11