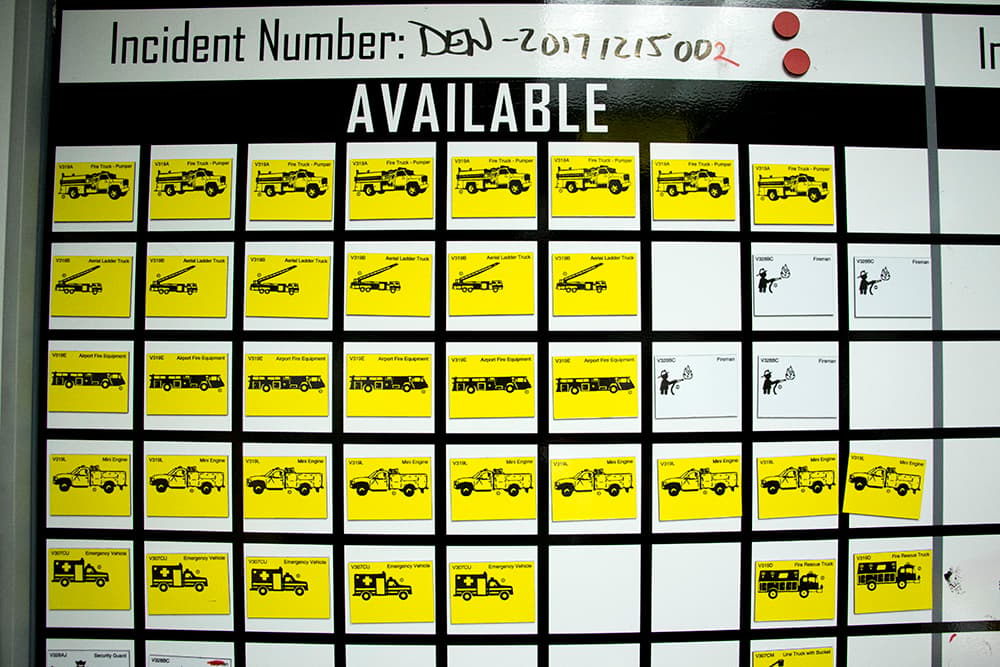

Denver conducted its largest emergency drill in a decade from a bunker-like facility in the basement of the City and County Building on Friday. Built in 1951 with the idea that it might have to survive a nuclear attack, the emergency operations center was bustling with 96 city employees from 36 departments dealing with imaginary casualties, medical response, road closures, shelter-in-place orders and more.

The simulated scenario involved a terrorist attack on a commercial building with large numbers of dead and wounded. One team took reports from the field while others coordinated the response or looked 12 to 24 hours ahead to what the next needs would be. From another room, observers from outside agencies evaluated Denver's performance.

By coincidence, the long-planned drill took place a day after Denver Auditor Tim O'Brien released a report that said Denver was "not prepared to provide mission-essential services in an emergency." The audit looked at the city's overall "continuity of government" plan and at 69 "continuity of operations plans" for 53 agencies that provide basic city functions. (Some departments, like Public Works, have multiple continuity plans for their various functions.) The results: 29 out of 69 continuity plans had not been reviewed or updated this year. Three agencies had not reviewed their plans since 2001, and five agencies did not have plans at all.

"Mission-essential functions include front-line, time-sensitive services," officials with the Auditor's Office wrote. "Many city agencies provide critical services for the health and wellbeing of some of Denver’s most vulnerable populations, including children who benefit from summer food and after-school meal programs. If a disaster took out everyday functions, everything from paperwork and permitting to other time-sensitive services could fail. This could also mean tax dollars would be wasted if city agencies were not able to do work in a timely manner."

Ryan Broughton, Denver's executive director of emergency management, said all of the individual recommendations in the report are sound, and his department will incorporate the audit results into their work. But he disputes the way the auditor characterized the city's preparedness.

"If the finding is that we are not ready, then tell me what ready looks like," Broughton said from the emergency operations center.

Broughton has been on the job for a just over a year. He regularly does disaster drills with different teams for a variety of scenarios, from tornadoes and floods to acts of terrorism. These teams include not just police and fire and paramedics, but transportation, community planning, human services and other city departments. The drills get progressively more challenging to push the teams and stress the system.

Broughton acknowledged that some departments don't get as much attention from his office as others do. He prioritizes the essential government functions identified by the Mayor's Office in its continuity of government plan, and not every department meets that criteria.

The five departments without continuity of operations plans are the Office of Human Rights and Community Partnerships, the Office of Children’s Affairs, the Office of HOPE (Housing and Opportunities for People Everywhere), which was created just last year, the Office of the Independent Monitor and Office of the Municipal Public Defender. Three departments had not certified what their "mission-essential functions" were so that they could be included in the continuity of government plan. Those were the Office of the Clerk and Recorder, the Denver Sheriff Department and the City Council (make your own jokes here).

The audit stresses that continuity plans ensure that government can keep functioning even if, for example, the offices where critical information is stored are destroyed or inaccessible. It used Human Resources as a test case. "Human Resources needs to be operational so that other city agencies can be appropriately staffed to resume normal, nonemergency operations," the audit said.

Per the audit:

Based on interviews with executive personnel from the Office of Human Resources, Emergency Management did not provide the agency with direction for creating a successful COOP plan. Emergency Management failed to give direction on what the agency needs to consider during planning, which systems or processes may be critical, and how best to anticipate the agency's needs in the event of an emergency. It appears that lack of guidance led to confusion about record prioritization for our test agency.

The Office of Human Resources COOP plan lists eight categories of records, including the agency’s compensation and classification database, as vital to the agency’s mission-essential activities. However, when auditors asked agency management about the records listed as vital in their COOP plan, they noted the compensation and classification database should not have been included because it wasn’t needed to support a mission-essential function.

... Vital records are essential for immediately restoring full operational capacity in the event of a disaster, as they include the data on which information systems operate. Because the Office of Human Resources has not received the appropriate guidance on how to identify vital systems, there is a risk that resources will not be properly prioritized for recovery of vital systems, further resulting in not have truly vital systems available when they are needed in the event of an emergency.

Broughton said he agrees with the recommendation that his office coordinate and communicate better with all city departments.

"We can do better," Broughton said. "We use a process of continual improvement."

The auditor also called out a three-month lapse in the city's access to its cloud-based storage services. Broughton said just as he was taking over, he learned the contractor was raising the price of this service fivefold. He didn't have that money in his budget, and it took time to negotiate a new contract. During that time, all essential documents existed in hard copy and in multiple electronic forms, he said.

Broughton said he's very aware that disasters can take unexpected forms and touch non-emergency functions of government. After a 2015 shooting in a San Bernardino social service office killed 14 employees of that agency, many distressed survivors also left the department. Mutual aid is more often thought of as something deployed by utility companies and fire departments, but in this case San Bernardino needed help from neighboring cities to make sure vulnerable people got the assistance they needed in a timely manner.

In the modern era, where everything depends on computers and the availability of electric power and internet service, something like a long-term power outage can be a serious emergency.

"They were making a legitimate point that we need to be prepared to run a marathon," Broughton said of the audit.

At the same time, just as ordinary people better use their time when they prepare for a house fire than for thermonuclear war, the most common and most likely disasters remain the old standbys: flood, fire, hail.

In the course of our conversation, Broughton asked me if my family has a disaster plan. I stammered a little. I actually have made changes in my home after getting trapped in Boulder during the 2013 floods and covering wildfires as a reporter. I have thought about how I store my important documents and how quickly I can leave my house with the most essential items to rebuild my life.

But I haven't updated this plan in a while or accounted for changes in my circumstances. I could be better prepared.

Broughton hands me a pamphlet from Ready Colorado, the Pack A Kit checklist. A lot of this same material is available online as well. It's real advice and also a metaphor. I am the Department of Human Resources, whose continuity of operations plan needs some refreshing.

When I asked Broughton at the end of our interview if there was anything he wanted to add, there was just this message for the community: "Our success is based on your preparedness."

Correction: This article has been updated with the correct spelling of Ryan Broughton's name.