Republicans have elected just one governor in Colorado in the last 43 years, but when they look at the Democratic field for 2018, they see a chance to do something Democrats traditionally have been better at: run the more centrist candidate.

"Speaking as a Republican, it's an opportunity for my party to command the political center, where the race is always won or lost," said John Andrews, former president of the state Senate and a fellow at Colorado Christian University's Centennial Institute. "You run to your base in the primary and to the center in the general, and it requires some agility. Republicans have a huge opportunity because the Democrats are running to the left."

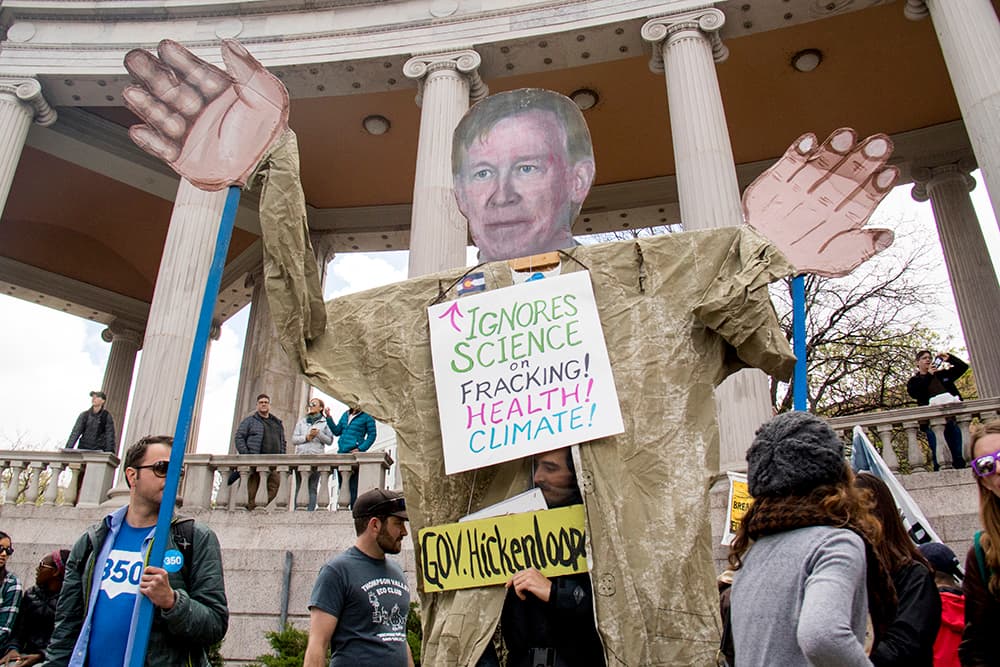

Democrats have elected a series of governors in then-Republican-dominated Colorado in part by choosing candidates with appeal outside the party base. Women's rights activists tolerated former prosecutor Bill Ritter's pro-life stance because there was a sense that such compromises were the only way to elect a Democrat. As a former small businessman and petroleum geologist, Gov. John Hickenlooper's background couldn't have been better if a consultant cooked it up in a candidate laboratory. Roy Romer also had a business background. Dick Lamm, while perceived as liberal in many ways, supports restrictions on immigration and warned about the dangers of multiculturalism. He would be an awkward fit in today's Democratic Party.

This year, with candidates proposing universal health care coverage, significantly more use of renewable energy and ambitious plans on education and growth, Democrats acknowledge that their field is further to the left than in previous elections. You catch glimpses of angst about this here and there.

Consultant Steve Welchert, who ran U.S. Rep. Ed Perlmutter's short-lived campaign for governor, predicted on Jon Caldara's political affairs show "Devil's Advocate" that there would be calls for former senator and Interior Secretary Ken Salazar to run after all. Salazar's decision not to run was a major factor in opening the floodgates for potential Democratic candidates. Perlmutter, a Democrat who repeatedly has won election in a suburban swing district, was widely perceived to have the kind of broad appeal that's worked for Colorado Democrats in the past.

"Don't be surprised if you hear drumbeats for Ken Salazar to come save the party. ... Somebody is going to say, 'We have to save the party. If Polis is the nominee, we risk losing the governor's office. That's too big a deal,'" Welchert said this summer.

That would be U.S. Rep. Jared Polis, who is widely perceived to be the frontrunner in part because his personal fortune allows him to fund his own campaign. He's also perceived as very liberal, in part because he represents Boulder, in part because of his support of renewable energy and the rights of unauthorized immigrants, in part, frankly, because he's gay. Those liberal tendencies are mixed with a libertarian streak on some issues, though.

Many activists believe the party is just following an electorate that wants more from its candidates.

"A decision was made many years ago with good leadership in the Democratic Party to run candidates who are very moderate," said Dickey Lee Hullinghorst, a long-time party activist and former Speaker of the House. "It could be that that formula doesn't work for us going forward. The young people coming up who are unaffiliated are more liberal than the Democrats sometimes."

Democratic political consultant JoyAnn Ruscha, who supports Polis in the primary, said Colorado's electorate is different now. It's younger, more diverse and, more importantly, voters want candidates who are bringing forth bold ideas to address real problems.

"If the conventional wisdom still held, Hillary Clinton would be president," she said bluntly.

There's a limit to what past elections can tell us about 2018.

Floyd Ciruli, a Denver pollster and political analyst, said Democrats have been successful at winning the governorship so many times because they nominated candidates that fit with the times. And the times have changed.

"The Democratic Party has moved to the left, and (the candidates) are more to the left," he said. "On the other hand, they are considered mainstream candidates. ... It's new territory."

Ciruli said Polis is a talented politician who can play up his libertarian positions and isn't a "wild man on oil and gas." He's also got a lot of money in a race that is expected to get very expensive.

"They need to nominate someone with a good personality and who doesn't seem too extreme," Ciruli said.

The national situation, with Republicans in charge of every part of the federal government, will favor Democrats at the state level, political scientists said. At the same time, individual factors matter enormously in governor's races.

"Hickenlooper was different than Romer, who was different than Lamm and Ritter," said John Straayer, a professor of political science at Colorado State University. "They seize an issue or there is a unique quality to their personality, and they're the top of the ticket."

“This may sound overly simplified, but to a substantial measure it’s personality, how much money was in the campaign, how well was the campaign run,” Straayer added. “The last couple years, the Democrats have been helped by the Republicans.”

Unaffiliated voters can participate in primaries in 2018, which could have unpredictable effects -- or little impact at all. For the first time in years, there won't be a senate race on the same ballot as the governor's race. Senate races help drive turnout in the general, though the effects are not entirely predictable either. In 2014, the same year that U.S. Sen. Cory Gardner, a Republican, unseated Democratic incumbent Mark Udall, Hickenlooper squeaked out a narrow re-election victory against challenger Bob Beauprez.

Colorado is becoming a more reliable Democratic state in presidential elections, but Republicans still dominate statewide offices below the level of governor, offices like attorney general, treasurer and secretary of state. As The Denver Post's John Frank recently documented as part of the "Colorado Divide" series, blue parts of Colorado are getting bluer and red parts are getting redder. The last presidential election saw traditionally Democratic parts of southern Colorado, like Pueblo and Huerfano counties, flip for President Donald Trump.

Republicans rejoiced when Trump carried Pueblo, seeing it as a sign that they could peel off working class Latino voters the same way that Trump won traditionally Democratic white working class voters in other parts of the country. Getting Pueblo to vote Republican would chip away at the Denver-Boulder blue block that helps deliver the governor's race for Democrats. But voters there didn't abandon the Democratic Party wholesale. U.S. Sen. Michael Bennet carried Pueblo even as Trump won it.

With loyalists of each party less interested in compromise than ever, the governor's race could well be won by the party whose voters are more excited about their candidate, and the energy in the Democratic Party right now is coming from the left.

"Off-year elections are about excitement," Ruscha said.

Who are the Republican centrists this time?

Andrews sees businessman and former state lawmaker Victor Mitchell, businessman Doug Robinson, State Treasurer Walker Stapleton and Attorney General Cynthia Coffman as all capable of running the kind of center-right campaign that could appeal to unaffiliated voters. Stapleton and Coffman have won statewide races before.

"That kind of breadth of appeal on the Democratic side isn't there," he said.

Democrats to whom I've talked tend to see Coffman as the most credible threat. She has a reputation as a strong campaigner and comes across as more moderate and pragmatic. They're skeptical, though, that Coffman can make it through her own party's nominating process, which favors conservative candidates.

Andrews sees Lt. Gov. Donna Lynne in a similar position on the Democratic side, though she is also a "bit of a mystery" as someone who has never won elected office. Lynne, a former health care executive, recently announced her intention to petition onto the ballot by gathering signatures from around the state. She cast this as an extension of her campaign, an opportunity to connect with voters around the state and in particular with unaffiliated voters who can now opt to vote in a party primary. Andrews said it's also likely to be her only path to the ballot.

Coffman may also need to petition onto the ballot, but that isn't an easy task. Consultants put the cost at around $250,000, as well as immense time and effort.

Republicans, meanwhile, have their own challenges with extreme candidates. Former party chairman Dick Wadhams said Tom Tancredo became the front-runner as soon as he declared.

"Republicans feel as good now as they felt in 1998," said Mike Beasley, deputy chief of staff for legislative affairs for Owens. "The Democrats seem divided with a variety of different candidates who see the world differently and wondering if they'll be able to pull their party together. The last time they struggled on that front, we won."

That said, "Democrats should see Republicans the same way," he continued. "It was just a few years ago that Tom Tancredo decided he didn't want to be a Republican anymore, and the Republican nominee got 11 percent of the vote."

Beasley said Polis would represent a formidable opponent, and Republicans shouldn't be so eager to face him.

Many Democrats feel just fine about their candidates.

In Pueblo and Huérfano counties, party activists said they aren't worried about the Democratic field being too liberal.

"I think the Democrats have a very good field of candidates," said Dale Lyons, chair of the Huerfano County Democrats. "Republicans think everyone is too liberal except for them."

In addition to Polis and Lynne, former state treasurer and CFO for the city of Denver Cary Kennedy, former state lawmaker and educator Mike Johnston and businessman Noel Ginsburg are seeking the Democratic nomination. Kennedy and Polis both have won statewide office before. Kennedy has proposed Medicaid-for-all and a plan to tackle affordable housing at the state level, but she can also point to her fiscal bonafides from her previous work. Johnston, meanwhile, has the support of prominent education reformers along with small donors.

Kennedy recently announced her intention to go through the assembly process, while Ginsburg plans to petition. Polis and Johnston haven't said what they'll do.

Lyons can't endorse a candidate in the primary, but she noted that people in the county have a history with Polis, going back to when he was a member of the State Board of Education. She remembers him coming to honor a teacher who won an important award and again when a school got its first computers. And despite the relatively small number of voters there, candidates are showing up for meet-and-greets. That kind of face time with constituents will matter more than ideology, she said.

"That makes a huge impression on the rural population," she said "Rural communities remember who comes out there and who does not. The southern part of the state is still struggling compared to Denver, which is booming."

When told that Republicans think the Democratic field is too liberal this time, Mary Beth Corsentino, chair of the Pueblo County Democrats, responded with a skeptical, "They would say that, wouldn't they?"

Corsentino acknowledged that Pueblo Democrats are conservative.

"They're conservative economically, and they tend to be conservative where families are concerned," she said. "They register as a Democrat, but they tend to be a conservative Democrat. But with all the stuff going on in the country, I think it's going to be a banner year for us."

And she sees particular challenges for some Republicans in Pueblo. As treasurer, Stapleton has fought for changes to the state retirement system.

"We have the highest number per capita of PERA retirees anywhere in the state," she said. "His stance on PERA alone will kill him here."

Like Lyons, she feels good about the choices Democrats have before them.

"I like all of them, to be honest with you," she said. "I don't know that they're too far to the left, and Hickenlooper is too far to the right in some people's minds."

Cheryl Cheney, chair of the Jefferson County Democrats, said the opportunity to hash out ideological differences is one advantage of the large primary field. She doesn't see any of the candidates as uniformly too liberal or too centrist; rather she sees candidates who might be to the left on some issues but more moderate on others.

"We have a broad spectrum of candidates to choose from on different issues," she said.

Since the 2016 election, there's been a big increase in volunteers and newsletter subscribers, and she's confident that whatever happens in the primary, Democrats will unite behind their nominee.

"There is a pervasive feeling that there are some pretty strong conservatives on the Republican side and that any of the Democrats would be better than the Republican," she said. "Especially with the strong response to events at the national level, there is a desire to elect a Democrat."

Hullinghorst said the national situation favors a Democrat, and Republicans haven't allowed their positions to evolve.

"The Republicans are salivating, but they are still backing a slate for a state that doesn't exist anymore," she said.

Ruscha thinks "not too extreme" is the least of what voters are looking for right now.

"It's safe to say that voters want to see candidates with ideas, and the status quo is not working for either party," she said. "The good men and women who look outside their office windows and see inequality and poverty and homelessness and shake their heads and say, 'That's a shame,' should not be leading the Democratic Party. We need people with bold ideas aimed at solving some of these issues."

"We need leaders who can unite the party behind the working class, behind people of color, behind women, behind the disadvantaged," she continued. "That's the party that will win up and down the ticket."