Next month, the Denver City Council may make a decision that could bring some of the most intense development of River North up to its borders with neighboring communities.

The latest plans envision buildings rising to 16 floors around the intersection of 38th Avenue and Blake Street. It would become one of the densest clusters to develop outside of downtown Denver. To sweeten the deal, the city could institute brand new rules about affordability and community amenities.

"I think we're in the third inning. We're a third of the way there," said Andrew Feinstein, a developer with various interests in the area.

"I think what we'll see is site after site located around 38th and Blake transition from warehouse uses to vertical development over the next three to five years."

It could be comparable in scale to the plans in the works for areas like the Gates Rubber Site and 41st and Fox.

"We’ve spent over a billion dollars on the A Line, and that is the one location ... that hasn’t really been thought out well — from design, from density, and inclusion," said Council President Albus Brooks.

"And so, we really wanted to have a conversation with the community."

The change is already visible.

Zeppelin Station is nearly done. The HUB, an eight-story project, is under construction. "RiDE at RiNo" will place 84 micro apartments on Wynkoop Street, just across from the station. The so-called Giambrocco Neighborhood will wrap around white industrial silos on six blocks nearby.

But the biggest plans, like the 16-story World Trade Center proposal, can't happen without the approval of a major change by Denver's elected leaders.

They'll wade into the discussion over the next few weeks, with a public hearing scheduled for February. Proponents of the new construction have laid out a vision that is meant to ease tensions by including extra requirements for community features and affordable housing, but the the thought of tall new towers on the horizon could spur intense new debate -- and some developers aren't happy either.

"From a lot of people I talk to, they feel this encroaching wave of development that’s coming toward Globeville and Elyria-Swansea is a serious threat," said Drew Dutcher, president of the Elyria and Swansea neighborhood association, an area just northeast of the new urban area.

"We had a lot of sort of philosophical discussions about this," Dutcher said. "Are we a city that has one central downtown of density and high-rises, or do we have multiple nodes in the city?"

Why here?

Developers are interested in 38th and Blake for pretty obvious reasons. It's riding in the wake of the massive redevelopment along Brighton Boulevard, which itself is fueled by the availability of relatively cheap, industrial land near downtown.

"Land prices -- they're really a fraction of what they are down by Union Station," Feinstein said.

This end of Brighton also has something special: It's the first stop along the A Line from downtown to the airport. Transit advocates and city planners argue that transit works best when lots of people are nearby, and developers seem to be buying in, too.

The city of Denver has made transit stations a centerpiece for its vision of mobility in Denver. Union Station and its crop of glassy high-rises are the obvious example of the potential, but you'll also find new apartment buildings around far-flung train stations in south Denver and the suburbs.

"We think it could be a really incredible welcome mat for visitors that are coming to the city," said Karen Gerwitz, president of the nonprofit World Trade Center Denver that will occupy part of the proposed tower that shares its name.

The creation of an urban district is bound to create consternation, especially one so close to residential areas.

In Elyria and Swansea, there's a growing fear that massive redevelopment and infrastructure won't leave room for single-family neighborhoods or the people that live there.

"The wave of rising land values are going to take over Elyria and Swansea and Globeville, and for a single-family home — it’s much cheaper to just combine them and build multistory units," said Dutcher, who represented Elyria-Swansea in the planning process for 38th and Blake.

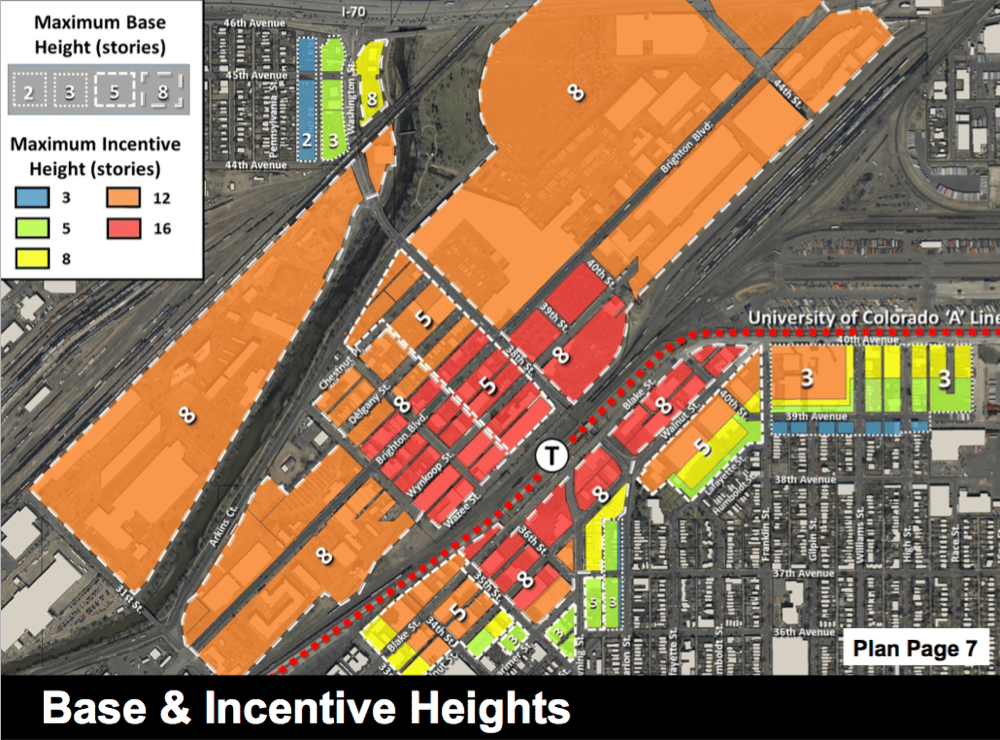

The city plan for 38th and Blake tries to balance the impact of development in a couple of ways. First, it "steps down" heights near residential areas. The residents of Cole won't be directly next to a 16-story building.

Moreover, the proposal tries to create affordable housing around the station by stepping up affordability rules.

"It's important to maintain the socioeconomic diversity of RiNo, and it's also important to maintain the character of RiNo," said Feinstein, the developer, who is co-chair of the River North Art District and serves on the steering committee for 38th and Blake planning.

To that end, Council President Albus Brooks has sponsored the creation of a set of rules that would incentivize developers to include community features and affordable residential units that go above and beyond the normal requirements around the train station.

In short, if developers include affordable housing and other community stuff, they can build higher.

"This plan achieves all of that. For the first time in the zoning code history, we will have a density bonus for affordable housing," Brooks said.

If it works, it would accomplish something that many have demanded: It helps to ensure that the city's explosive growth brings more benefits to the community at large. The question is just how much it will deliver.

The details:

Denver already has citywide affordable-housing rules. A typical five-story building in this area might have to build one affordable unit, or they could pay a fee of $112,500.

But if that developer wanted to access the extra height allowed under this new system, the affordable housing requirements would get much steeper. Going to 12 floors, for example, would require a total of 10 affordable units. That's more than triple what would be required without the incentive program.

The 38th & Blake rules also require that the extra affordable units be built within the building or the 38th & Blake area. The units would be for people making a maximum of 80 percent of the area median income, or $67,120 for a family of four.

Developers building retail and other non-residential space would also have to pay extra for height. A 12-story commercial building would have to pay an extra $714,000 in incentive fees -- or it could agree to provide low-rent space for a nonprofit or for community services such as child care, or space for artists.

The proposal also introduces new design rules. Buildings will have to get thinner as they get taller, a tactic meant to discourage blocky blocks. No parking will be required within a half-mile of the station, which is meant to reduce the amount of space spent on parks. Also, buildings near the river would be oriented toward the water.

The changes also will increase the overall maximum heights even when developers don't build extra affordable units -- just to a lesser extent.

What will happen?

To an extent, the affordable housing incentive has brought some neighborhood leaders on board with the plan. “We’re expecting this with what’s going on in RiNo and all the development that’s happening. At least this way we get affordable housing," as Mike Dugan, of the Cole Neighborhood Association, previously told Denverite.

For his part, Dutcher (of Elyria-Swansea) also sees a strong need for affordable housing, but feels that this is only a "nod" toward it. He believes that the plan is primarily meant to allow higher density, and he's disappointed in what he believes is a lack of "robust public discussion" about such important topics, he said.

Beyond the community, the central question is whether or not developers will bite.

"In a lot of places in our city where we’d like taller buildings around our light-rail stations, the market hasn’t produced them. I’m just curious how the market’s going to respond to this," said Councilwoman Kendra Black, calling out the 41st and Fox station in particular.

"That's always been the fear," Brooks responded. But market-rate developers already had come with plans to go for 16 floors and 20-plus units, he said. "It's impressive."

But it has been harder to convince commercial developers to go taller, he admitted.

And the proposal is throwing a wrench into another buzzed-about development.

Bernard Hurley had laid out plans for a $250 million mix of towers rising to 12 floors, including residential, retail, hotels and restaurants. Now, though, he says that the financial numbers in the plan aren't working for him. He had planned extensive public space for his project, which he had hoped the city would count as a "community benefit" -- thus saving him significant money.

He has learned that he won't get any credit for public space, he said. He doesn't think he can afford to pay the incentive fee, and he's unsure he can subsidize rent for a "community benefit." He anticipates that his development, Hurley Place, would be losing significant money already in order to attract restaurants and other businesses.

"I don't have a problem with the affordable units — I believe in affordable housing anyway. It’s the office and the hotel. You’ve got to pay a pretty large per-square-foot price if you don’t do the community-serving benefit or meet that criteria," he said.

A city spokeswoman said that the planners had considered numerous "community benefits" to encourage, and decided against counting public space. "Open space is desirable in the area but doesn’t necessarily relate to affordability, and it’s difficult to quantify the economic value of a plaza, for example, vs. an affordable unit in an incentive system," wrote Alexandra Foster in an email.

For Hurley, the future's up in the air for now. He plans to take a "deep dive" reassessment of his project now that the final details have emerged.

"I want to do iconic architecture and have a legacy project, and if I can’t do that, then I’m not going to do it."