When it comes to Denver's family neighborhoods, we know two things for sure: where families live now and where they lived before. Easy.

What's difficult is predicting where they'll be even five years from now.

You can take a look at what's being built for clues -- those cranes looming over the skyline aren't building a whole lot of family housing in north and central Denver. On a smaller scale, slot homes and other construction are changing the character of neighborhoods that have long been family-oriented. And the best data-driven guesses back that up, saying that families will continue to follow new, more family-friendly development to the east while numbers in central and west Denver drop.

Daniel Jarrett, chief economist at the Denver Regional Council of Governments (DRCOG), said analyzing census data for households with families over time and at the tract level is not information the agency has readily available. The best way to get a sense of where families live in Denver, he said, is to look at Denver Public Schools data tracking where its students live.

More and more, families live in northeast Denver. Less and less, they live in north Denver.

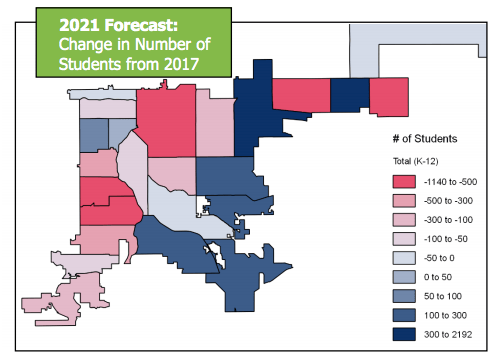

Take a look at the heat maps provided by DPS that show where students who attend DPS schools live:

Let's break down what we're seeing here.

Family populations in northeast Denver neighborhoods have exploded. In Montbello, there were 7,259 students in 2002 and 9,718 in 2017. Gateway-Green Valley Ranch saw the largest increase in the city — from 2,721 to 8,352 — and rapidly developing Stapleton grew to 5,173 students in 2017 from just 17 students in 2002.

As Brian Eschbacher, executive director of Planning & Enrollment Services at Denver Public Schools, points out, it's all about new housing. In 15 years, Stapleton went from hardly any homes to something like 7,000.

The decreases in student population have been far smaller, and they're clustered northwest of I-25. Highland is down to 664 students from 1,334, and Villa Park dropped from 2,023 to 1,609. The largest drop happened in Sunnyside, which got down to 1,281 students from 2,143.

"Sunnyside has seen declines almost every year, and especially when you start to look at the last three years, which is when the housing crisis has really increased in neighborhoods like that," Eschbacher said.

DPS also tracks changes in demographics, and it shows big changes in the neighborhoods experiencing the largest changes in total student population.

Since 2005, Gateway-Green Valley Ranch and Montbello — two neighborhoods in that far northeast region — saw between 12 and 13 percent increases in their Hispanic student populations. The African American population is down between 14 and 15 percent in those neighborhoods. The northwest region, meanwhile, has seen sharp decrease in Hispanic students. DPS data says it's down about 16 percent in Sunnyside, about 18 percent in Berkeley and about 31 percent in the Highlands.

Separate data looking back five years back shows the number of students in free and reduced lunch programs — meaning they come from low-income households — is down 6 percent.

A few gaps to note: This doesn't account for students who are homeschooled, go to private school or go to school in another district. According to the Colorado Department of Education, there are 7,751 students living in Denver but attending another public school district in Colorado.

Let's take a look at the forecast.

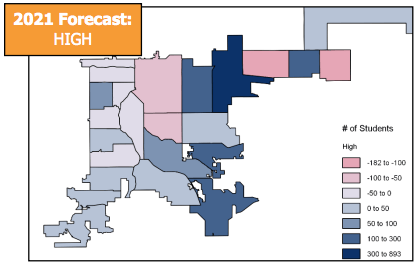

It's harder to look 15 years into the future than it is to look 15 years into the past, but a Strategic Regional Analysis produced in the fall of 2017 by DPS, the Denver Regional Council of Governments (DRCOG) and Shift Research Lab offers a look five years ahead. Among other things, it offers regional and neighborhood predictions for the number of children residing in the DPS district expected to enroll in DPS schools.

Here's the citywide forecast:

According to the analysis, more than half of Denver’s 78 neighborhoods are forecasted to have declines in the number of children attending DPS schools. Stapleton and Gateway, which you see in dark blue, should notably buck the trend.

The forecasts are also broken down by grade range, and predict decreases in most elementary schools, an even mix of growth and decline across middle schools and stagnation or growth in most high schools. The analysis notes that elementary enrollment has been declining district-wide since 2014, and that lower post-recession haven't reached middle schools yet.

As you can glean from that first citywide map, a couple regions should fare better than the others. The near northeast and the southeast (which will be defined below), are the only two regions out of six likely to see gains.

Far northeast: A conservative forecast shows some decline in DPS students residing in the far northeast — from 18,359 to 17,299 — but the analysis notes that it's pretty unpredictable. If development plans for around 4,000 units in the DIA neighborhood come to fruition sooner than expected, there could be much more growth.

Otherwise, things should settle down a bit here. Gateway is expected to continue to see growth, potentially adding anywhere from 300 to 2,192 students. Montbello and Green Valley Ranch, on the other hand, are likely to see big drops — losing 500 to 1,140 students. The DIA neighborhood should stay about the same, with a slight decrease.

Near northeast: The analysis predicts an increase in the near northeast region — from 17,378 to 19,697 students — mostly because it's expected that Stapleton will continue to grow.

Park Hill is the only neighborhood in the region for which the analysis predicts a decrease, likely a drop of 100 to 300. The rest — East Colfax, Lowry Field, Montclair, Hale, Hilltop, Windsor and Washington Virginia Vale — will see growth.

Central: Enrollment declines are forecasted to continue, and at a quick rate, in central Denver thanks to a particularly steep rise in housing costs and a trend of families moving away before their children are 5 years old. On top of that, most of the new construction in the region is of small apartments that tend to be occupied by young Millennials and empty-nesters.

The region includes a large number of neighborhoods: Globeville, Elyria-Swansea, Five Points, Cole, Clayton, Whittier, Skyland, City Park, City Park West, Capitol Hill, North Capitol Hill, Cheesman Park, Congress Park, Country Club and Cherry Creek.

The total drop is expected to be between 500 and 1,1140 students in the northern two-thirds of the region and between 100 and 300 in the southern third.

Northwest: The analysis for the region that includes Sunnyside and West Colfax says to expect continued declines in student enrollment, thanks to continually rising housing costs and the development of multi-family units, but it'll happen at a slower pace than what the area experienced in the last five years.

It's predicted that student enrollment will drop from 10,139 to 9,639.

Southwest: Rising housing costs are cited for a predicted decline in the southwest region, too. The total student population is expect to fall from 21,060 to 19,208. Elementary schools will be the hardest hit of anywhere in Denver, with an expected loss of about 2,000 students.

Neighborhoods in the region include Marston, Fort Logan, Bear Valley, Harvey Park, Harvey Park South, College View, Ruby Hill and Athmar Park.

Southeast: Things look much better for families in southeast Denver, where housing is more affordable. That includes Kennedy, Hampden, Hampden South, Southmoor Park, University Hills, University Park, University, Platt Park, Rosedale, Overland, Goldsmith, Virginia Village, Cory-Merril, Belcaro,Washington Park, West Washington Park and Speer.

Student enrollment should rise to 11,445 from 10,860 by 2021, the analysis says.

There are a handful of underlying assumptions in the analysis worth noting:

- A recession does not occur in the forecast period

- There is no significant change in the labor market or permitting process that would disrupt the building of new homes

- The housing price points are constant

- Capture rate (the fraction of newborns that will enroll in five or six years) and cohort survival rate (the fraction of a grade that will remain in DPS the following year) are an average of the three previous years

- School quality and programs are anticipated to remain constant

Emphasis mine on the third one because it feels like the biggest "if."

There are also some things we don't know:

- In which neighborhoods those 7,751 Denver kids leaving the city for school live

- How many families are moving between neighborhoods or moving in and out of the city all together

- How demographics will change going forward

There are a few reasons why neighborhoods lose and gain families, and they're not always easy to untangle.

First of all, there's the post-recession birth rate. Between 2010 and 2016, the birth rate declined 8 percent in Denver and across the U.S. So, some of the change we see is simply because fewer people are having children.

And as the birth rate was dropping, Denver housing prices were soaring.

"It’s hard to unwind which is which because they hit at the same time," Eschbacher said.

We do know that regardless of birth rates, rising costs are driving families and people in general out of Denver and out of particular neighborhoods. In some cases it's as straightforward as this: "The higher the housing price, the less families that are going to live there," Eschbacher said. But it's not always that simple.

Xavier Gitiaux, the research economist at DRCOG and lead on the Strategic Regional Analysis, said housing costs can play out differently in different neighborhoods depending on history and unit sizes. It matters whether a neighborhood has historically been home to a lot of families, it matters what type of housing already exists there and it matters what type of housing is being built there.

"It’s tricky," he said. "You’re going to see high-cost units in Stapleton with a lot of kids, and you’re going to see more mid-cost units in Montbello with a lot of kids, and you’re going to see more high-cost units in Cherry Creek with no kids. It varies with the historic context. We really look neighborhood by neighborhood when we look at the effect of cost.

"...We also found that the type of developments that are being built can affect the growth. Most of what is built is more likely to have no families at all. It’s mostly younger household, single-person households."

That's part of what's causing turnover in northwest Denver, Councilman Rafeal Espinoza said. His district — District 1 — includes Sunnyside, Highland, Jefferson Park, Berkeley, Chaffee Park, Sloans Lake and part of West Colfax.

"They’re leaving because of the character, they’re leaving because of the rent, they’re leaving because they’re getting a sweet deal on their property because someone is overpaying," he said. "They’re also under the belief that when you get a big, nice sale price that’ll take care of you someplace else, but the cost of housing everywhere is hard to manage. They’re leaving because their tax assessment went up."

Espinoza recently spoke to a grandfather who lives in Jefferson Park with his kid's family. He's spent his entire life in north Denver, but he's been shopping his house to developers since a new slot home went in next to his little brick bungalow because "it’s not his community anymore."

The councilman, a Jefferson Park resident himself, said "there's not a day" when constituents don't come to him with similar stories. He's watched as lower income, larger households are replaced with larger income, smaller households.

"We’re scraping 800- to 1,200-square-foot houses and putting in 1,200- to 1,500-square-foot slot homes on them with less bedrooms," he said. "... No one’s building affordable five-bedroom houses, and those are definitely for a multigenerational community."

In northeast Denver, Councilman Chris Herndon sees change as a good thing.

"If you just drive through Stapleton regularly, you see these new communities continue to form," said Herndon, who represents Stapleton, Park Hill, East Colfax, Northfield and a piece of Montbello.

There has been and continues to be space to grow into there, rather than scraping homes to build new ones, and what they're building are homes for families. That means they're also building, expanding or improving things like libraries, parks, community centers and bike lanes, Herndon said. What his constituents want and what he works to get are measures for improved public safety, better traffic management and other transportation options. Thanks to a voter-approved bond measure, they'll begin several millions of dollars of work adding sidewalks.

Herndon says all of the neighborhoods in District 8 are family friendly, including the one that's seen a decline in students over the past 15 years: Park Hill. His daughter goes McAuliffe International School, a school he said keeps expanding.

What both Gitiaux and Eschbacher pointed out is that some of this is just the natural cycle of a neighborhood. Take Green Valley Ranch, for example. Gitiaux said there's not much left to build out there and the families there probably aren't leaving anytime soon, so the kids are aging into middle school and high school. Soon, they'll age out of a school and likely leave home.

"I think the family-friendly nature of some of the neighborhoods is in the way the generations turn over," Eschbacher said. "In Wash Park, they’ve grown by a pretty high percentage. Some of that is the evolution of the families who live here. They have children who gradate from school and then there aren’t children living in the house, but then they sell and move to another neighborhood and another family moves in."

In short: sometimes it's just the circle of life.