In June, a group of concerned citizens met with Denver officials and EPA representatives to talk pollution. It did not go well. The meeting location changed at the last minute and some members of the Citizens’ Advisory Group, or CAG, called foul.

“This is outrageous,” wrote one member in an email. “EPA and Denver should be held accountable for this mess. Typical.”

They nearly boycotted the meeting but, eventually, the group made their way into the Denver Coliseum where representatives from the city and the EPA awaited to begin their last formal discussion on the Superfund site beneath Globeville Landing Park.

But the citizens' group wanted to talk about more than the Superfund cleanup. They wanted to talk about air pollution and the higher rates of asthma and heart disease for residents of Globeville and Elyria Swansea, mainly people of color. They wanted answers and they wanted solutions.

Denver is on the forefront of a national movement in air quality measurement that's embracing networks of cheaper monitors to create more detailed understandings of pollution in cities and put that knowledge in the public's hands. It's the beginning of a shift that might offer more for concerned groups like the CAG although, in the end, they may still be left unsatisfied.

Understanding pollution better may not make it any more palatable.

Nailing down environmental sources of disease, especially air pollution, is extremely complicated.

The EPA has a handful of stations around Denver that measure 6 "criteria pollutants," each tracked by law as part of the Clean Air Act. Each pollutant is regulated in a slightly different way; whether or not a contaminant is out of compliance is measured in terms of averages, often over three years. In the Denver metro area, only ozone is currently above federal limits.

Historically, air quality measurement was limited to enormous, extremely expensive devices that cities could only place in a handful of locations. That's still mostly true today. That's a problem because air pollution can be extremely location-specific, and the few monitors scattered around the city might not represent what’s happening in one person’s backyard.

Neighbors like those who gathered at the Superfund meeting want to see readings in detail, but each monitor generates hundreds of thousands of entries. And despite the mountain of data collected every day, there are geographic gaps between the monitors. Researchers use computer-generated models to fill in the rest.

And once it's all measured and modeled, the information analysts get from their systems isn't usually clear, especially for non-scientists. Discussion during the CAG meeting was constantly interrupted to pause for explanation.

All of this plays into some concerned citizens' distrust and their rocky relationship with officials.

Communication might be getting better, with the help of some new tools.

In just the last few years, pollution-sensing technology has become significantly cheaper. At the same time, public regulators and private researchers are beginning to take an interest in plain-English communication. The goal, they say, is to better arm communities with knowledge.

For now, though, concerned citizens are left to trust officials’ analyses.

“I do not trust your modeling,” Elyria Swansea resident Jorge Merita said at the CAG meeting.

“Fair enough,” Denver’s Air Quality program manager, Michael Ogletree, responded.

“What I want to know is exactly how does the modeling correlate to the machines that you already have been testing? And don’t send me to your website. Because you don’t even know if I have a computer,” Merita said. “Give me something I can read.”

As one of the city's lead air analysts, Ogletree is just the guy to make sense of all the data collected by the EPA. He's also one of the key players operating a special, city-operated air station at Swansea Elementary School that's been monitoring a huge range of pollutants for a year and will continue to do so as the I-70 expansion construction kicks up dust for the next few years.

Ogletree already creates quarterly breakdowns from the Swansea datastream, but he admits that communicating this stuff is hard. In fact, he ran focus groups earlier this year to figure out better ways that they might express the facts.

“Previously we would put out reports, and people would express not fully understanding what those were," he told Denverite. "By co-creating air quality dashboards with the community, we could provide something that is understandable and usable."

This research is part of a larger project funded by Bloomberg Philanthropies Mayors Challenge, a four-year grant that's also paying for 10 custom sensors that Ogletree helped design with Lunar Outpost, a startup based in Golden that specializes in atmospheric monitoring. Ogletree said cities don't often take a hands-on approach in building their own monitors; that wasn't practical even a few years ago.

"The sensors themselves have really started to improve at a rapid pace," said Justin Cyrus, Lunar Outpost's founder. That, coupled with more efficient electronics and cheaper batteries, has allowed the city to take research into their own hands.

And more sensing is crucial to get an accurate picture of air quality. The current method to predict pollution based on a few data points has its limits.

"Unsurprisingly, those models aren’t great," Cyrus said. More readings means a more detailed idea of what's going on.

"Each five or ten of these things that you put out there, your modeling increases substantially," he said.

Last week, Ogletree's team deployed three of those sensors to area schools. Six more are stationed alongside the EPA's $100,000 monitors to help make sure the smaller, cheaper ones are accurate.

The results from these new units will eventually be displayed online and in schools, designed with guidance from his focus group findings.

"Hopefully, if they understand parts of it, it’ll help these concerns a little bit," he said.

Another effort -- using wearable air quality sensors -- is also in the works.

This summer, researcher Dr. Lisa Cicutto and her team have begun deploying sensors for people living in Globeville and Elyria Swansea as part of a project led by National Jewish Hospital. While much air quality research still centers around fixed, outdoor sensing, her study is aimed at following a resident's exposure inside and out, to wherever that person might encounter pollution.

Her participants will wear monitors for short periods during the next three seasons, and keep detailed notes about their activity to provide context for pollution readings.

She thinks the project might be the first of its kind. While personal monitoring has been used before, she said it's never been methodically redistributed to residents who helped collect the data.

"It's extremely important that people understand what’s going on," she said. "They can make sense of it and decide whether or not they have concerns and then what they might do."

This is especially true for patients with asthma, Cicutto's specialty, whose conditions vary greatly and thus require a lot of situational understanding to treat effectively.

In her own focus groups, Cicutto found that healthcare providers and regular citizens were equally confused with the language of air quality standards. People didn't know if pollution like particulate matter should be below or above a standard. In school, she said, we're taught to exceed standards. That's not the case here, and she wants to make sure information comes across easily so people can access it.

Her participants, she said, are "quite thankful in terms of learning whats going on inside, and that they have the chance to participate and learn."

Better understanding of pollution is not in itself a solution, it's only the first step.

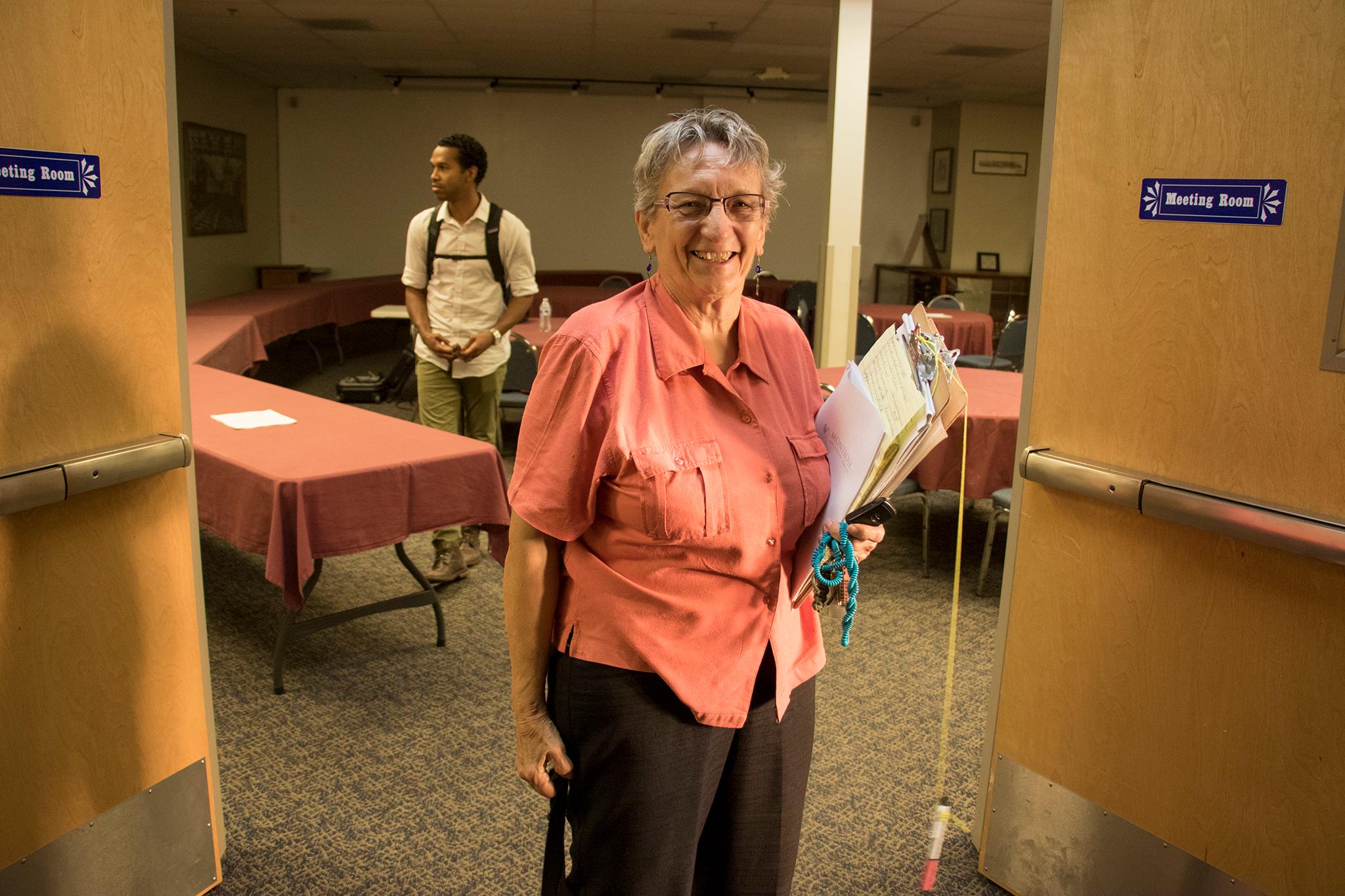

Back at the CAG meeting, concerned citizen Fran Aguirre had questions:

"I want to know who is doing what about the problem of the pollution in 80216," she asked.

"None of the measurements ... outside of ozone have exceeded any national ambient air quality standards," Ogletree responded.

"And that’s true of the benzene in the air?" Aguirre asked.

"Benzene doesn’t have a national ambient air quality standard."

"Why not?"

"That’s a much more complicated question," said Ogletree.

At some point, there's a limit to what local authorities actually have the power to do.

On one hand you have Aguirre, Merita and other concerned citizens who know there are health problems in the neighborhood but can't seem to figure out how to address them.

On the other is Ogletree and Denver's Department of Public Health and Environment, who are not regulators. They only have the power to take measurements and make recommendations. The EPA, which was also represented at the meeting, can also only act within federal laws' allowances. This is cause for more friction.

"Who is doing what about the problem of the pollution in 80216?" Aguirre asked, frustrated. "What can you do?"

Researchers like Ogletree and Cicutto hope that more comprehensive understanding into where and when pollution is at its worst can help locals avoid it by staying inside or finding another park to play in. It's a short-term fix avoiding symptoms rather than addressing sources, but Ogletree says it's a start.

"That’s really what we’re trying to do with our program. Just because pollution doesn't exceed a national air quality standard doesn’t mean that it’s not impacting your health," he said. "I talk a lot about limiting exposure because that is something we can do immediately. Longer term, we’re looking at impacting the source of pollution. finding ways to influence traffic patterns or reroute trucks away from schools, but those are just much longer goals."

For the most vulnerable Denverites, kids in particular, dodging the worst air might be the only thing anyone can do for now. It's the reason Ogletree has focused on schools with his new slew of sensors. And because cars contribute significantly to air quality, he's also focused on changing drivers' habits, including a campaign to reduce idling engines near schools.

Cicutto said her study has already revealed other information that will help people avoid health risks. While exposure to highways is certainly problematic, she said some of the biggest spikes in particulate matter were observed when a person wearing a sensors was cooking inside.

"People had no idea," she said, "and they didn’t use vents."

All of this, cooking and idling cars and proximity to two major interstates, plays into health risks that north Denver neighbors face. And yes, part of this is an issue of class.

"It is epidemiologically certain that living near a highway … you are clearly exposed to much higher levels of pollution," said Anthony Gerber, an associate professor of medicine at National Jewish who also sits on the state Air Quality Control Commission (though he stressed he was speaking solely from his own perspective in his comments).

"It's unfortunate as a society, we have decided some people will live near a highway," he said. "Sometimes that's socioeconomics."

On Tuesday, the CAG met again, this time as a self-directed group. Ogletree was there, presenting his project's new progress in hopes of easing some fears.

As far as the extra sensors go, "More is better than none," Merita said. "It's good, but it doesn't make me feel good."

Aguirre said she likes that face time with local authorities gives her a chance to provide input, but she still feels removed from what's actually going on.

"I just feel like, always, the powers that be have to spout what the going language is. They can't change stuff," she said. "I guess that's where we always end up. You have to trust the word of the people doing the job."

The time is coming when we might all be equipped with our own sensors to keep tabs on the air around us. But for now, even as technology opens the door to new insights, people like Aguirre still have a disconnect to reckon with.

"When you know there are sick people in the area ... it's difficult," she said. "We're limited by who's interpreting."