In some ways, Colorado Boulevard still looks like it's 2005.

While wide swaths of the city's center has been torn down and built again over the years, this busy roadway has stayed just about the same. It's lined in southeast Denver with office towers and big-box stores, a Whole Foods and every mid-sized franchise you can imagine.

Practically the only thing changing on this lucrative stretch is the increasing traffic -- at least for now.

"Change is very rare in south Denver," said Jimmy Balafas, a 41-year-old developer. "It's a very stable, stable street."

But Balafas, working with his family business, sees a chance to make a breakthrough. Kentro Group has won the rights to buy about 13 acres at Arkansas Avenue where the Colorado Department of Transportation once had its headquarters. Balafas cofounded Kentro with his brother George and with Yianni Bellis.

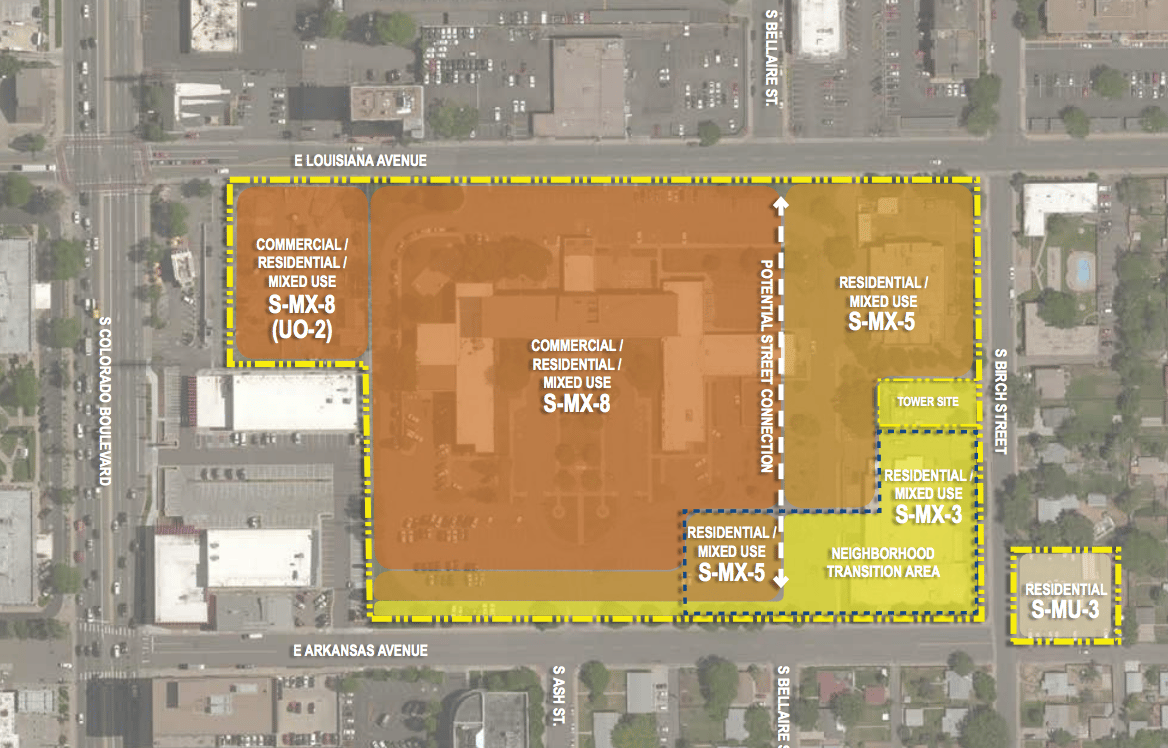

Now, they're preparing a plan that would create the kind of "mixed use" development that is more common in the city center, with at least 150 below-market apartments and enough retail to fill a large city block. A proposal that would go before the Denver City Council this year would allow buildings to reach eight floors on parts of the Arkansas property, which is in Virginia Village.

"We’ve been eyeing this site for a long time. It’s just a rare piece of property that’s 13 acres in the middle of a city," Balafas said.

In theory, it's the kind of development that the city government is trying to encourage: taller, mixed-use buildings, rather than big-box stores, on a busy corridor. The development team is keying in on urbanist buzzwords -- things like multi-modal transit, and living and working and playing. Standing about a mile north of a rail station, they argue that it's the ideal site to try something new.

They also know that change is hard. They've mounted a voluntary campaign of monthly meetings throughout 2018 -- where they've met crowds of up to 100 people, and all the usual concerns about traffic and density.

Here's how it would work.

The developers argue that they're actually downzoning the property. The current zoning allows buildings up to 12 floors, while the new proposal knocks that down to three, five and eight floors at different spots. The change would reduce the amount of residential space allowed on the site, while newly allowing retail, they say.

Under an agreement with the city, the site would have to host 150 apartment units for people making up to 60 percent of the area median income, or about $49,000 for a family of three. The developer also could pay a fee instead, but Balafas insists that they'll actually build the units.

The site still belongs to CDOT. If the council approves the rezoning later this year, the city would buy the property and re-sell it to Kentro around December. The city has the right of first refusal, which is why they're able to act as middle man and introduce affordable housing requirements on the sale. Denver officials chose Kentro from a pool of potential buyers.

Kentro ultimately would pay about $19.3 million for a package including the Arkansas site and another site on Holly Street, where it plans to build and sell up to 180 homes and rent up to 60 affordable units for seniors. The two sites total 23 acres.

Development could cost Kentro north of $100 million, Balafas said.

So far, they've met a mixed reaction.

At a meeting in July, traffic came up more often than any other issue.

"This is going to make it five times worse. It’s insane. You guys move over here. You live here for a little while" said attendee Stephanie Strand.

Kentro has commissioned the firm Kimley-Horn to study traffic in the area, but they haven't laid out any plans for traffic management. They also say they'll try to position the site as a hub for buses and even on-demand shuttles, all of which could connect the site to the rail station about a mile south. It's flanked by bus lines on Colorado and on Birch Street.

Meeting attendee Tom Fields saw no hope for drivers: "Basically, they want everybody running public transportation and bicycles, and one of the ways is to crowd up the streets as much as possible, so that you’re totally frustrated, driving," said Fields, who drove in from his home in unincorporated Arapahoe County because he's so frustrated with development.

Others were doubtful that a building on Colorado Boulevard could really discourage its residents from owning and using automobiles, as the developers have claimed they'll do. And Councilman Paul Kashmann has said he's a "tad skeptical" about the scale of the project, saying worsening traffic is a concern.

More recently, Kashmann said that the site has real potential to worsen the "gridlock" on Colorado.

"The entire personality of what’s there could change a bit," he said, stressing that Kentro hasn't published its detailed plans yet. "We do know there’s going to be commercial, residential and retail there, and it's going to be a lot of traffic coming off there that we’re not used to."

In the long run, he said, Colorado Boulevard needs to shift to transit, potentially including bus lanes or other options.

"We’re not going to solve this by ourselves. We’re going to need community input. We’re going to need city support, city solutions," Balafas said, describing his company's plan as "smart growth."

There were signs that the developers are finding fans.

The meeting in July at times turned into a snippy back-and-forth as residents debated city planning. After one woman suggested that "nothing" or a park be built on the site, another replied that she could "be the police of all the vagrants."

Kristin Jones, who has lived in Virginia Village for a year, urged the developers to go more urban, with less room for cars.

"I think if there's too much parking, it feels less safe, it’s less attractive, and there’s less room for building affordable housing," she said. Balafas responded that he didn't "want to under-park it," but he noted that the apartments will share some spots with retailers.

Eric Evert, a father of two young children and a member of the area's neighborhood association, said that the plan could change the neighborhood for the better.

"That’s what we’re hoping for, what we’re pushing for — goods and services that the neighborhood itself can walk to, and not have to deal with Colorado Boulevard," he said. "Heck, it’s not getting any better."

If the council rejects the rezoning application, Kentro's deal won't go through, and the land could reopen to other purchasers. If it's approved, construction likely would take several years.