UPDATE, Mon., Oct. 22: After hours of debate and discussion last week, the Denver City Council passed the 60-year minimum "by consent." In other words, members deemed the law noncontroversial and not in need of more public debate, so they passed it unanimously without discussion. See below.

When the clock strikes 20 years, some affordable housing becomes unattainable, market-rate real estate.

That can mean displacement or homelessness, and it's thanks to a Denver law that says city-subsidized affordable homes only have to remain that way for a minimum of 20 years (though the average is 29).

The Denver City Council voted Monday night to publish a bill that would extend that minimum to 60 years. They'll vote on that bill next Monday. The goal was to shore up the city's stock of dwindling affordable housing through preservation, which can be cheaper than building new units. The proposed policy stems from the city's five-year housing plan, which prioritizes long-term affordability.

"If I have the opportunity to send a signal to this market about what's expected in this city, and I can send this message tonight that what's expected is 60 years, I need to send it," said Councilwoman Robin Kniech.

No one disagreed on if a policy for longer term affordability must exist, just how. Some affordable housing developers and council members said the council moved too fast -- that the city lacks dedicated funding to ensure affordability 60 years into an unknown future with unknown market fluctuations, and that the ordinance should include more specific regulations that nonprofit developers could depend on. They need loans to build, but uncertainty could sap new home construction, they said.

"There's too much of a big question mark," said Andrea Barela, CEO of NEWSED Community Development, a nonprofit developer. "It's got to be about more than just lengthening affordability. There has to be a strategy."

Kniech offered an amendment, which passed, that would delay the implementation of the law until February 2019, which would give the nonprofit housing sector and elected officials time to iron out more details. About 2,000 income-restricted apartments -- 8.5 percent of the city's "affordable" rental apartment stock -- could turn over in the next five years when restrictions expire, according to the Office of Economic Development.

In 15 years, Kniech said, she hadn't seen one nonprofit housing development flip to for-profit after the income restrictions expired.

"I believe this measure levels the playing field," she said. "Because right now mission-based organizations have to trudge through and find solutions because their mission requires them to, and it's hard, and we can make it easier for them. Where as for-profits can dodge our efforts, can let their covenants expire, and sell them at a profit and walk away. And they've done it. And that's unacceptable to me."

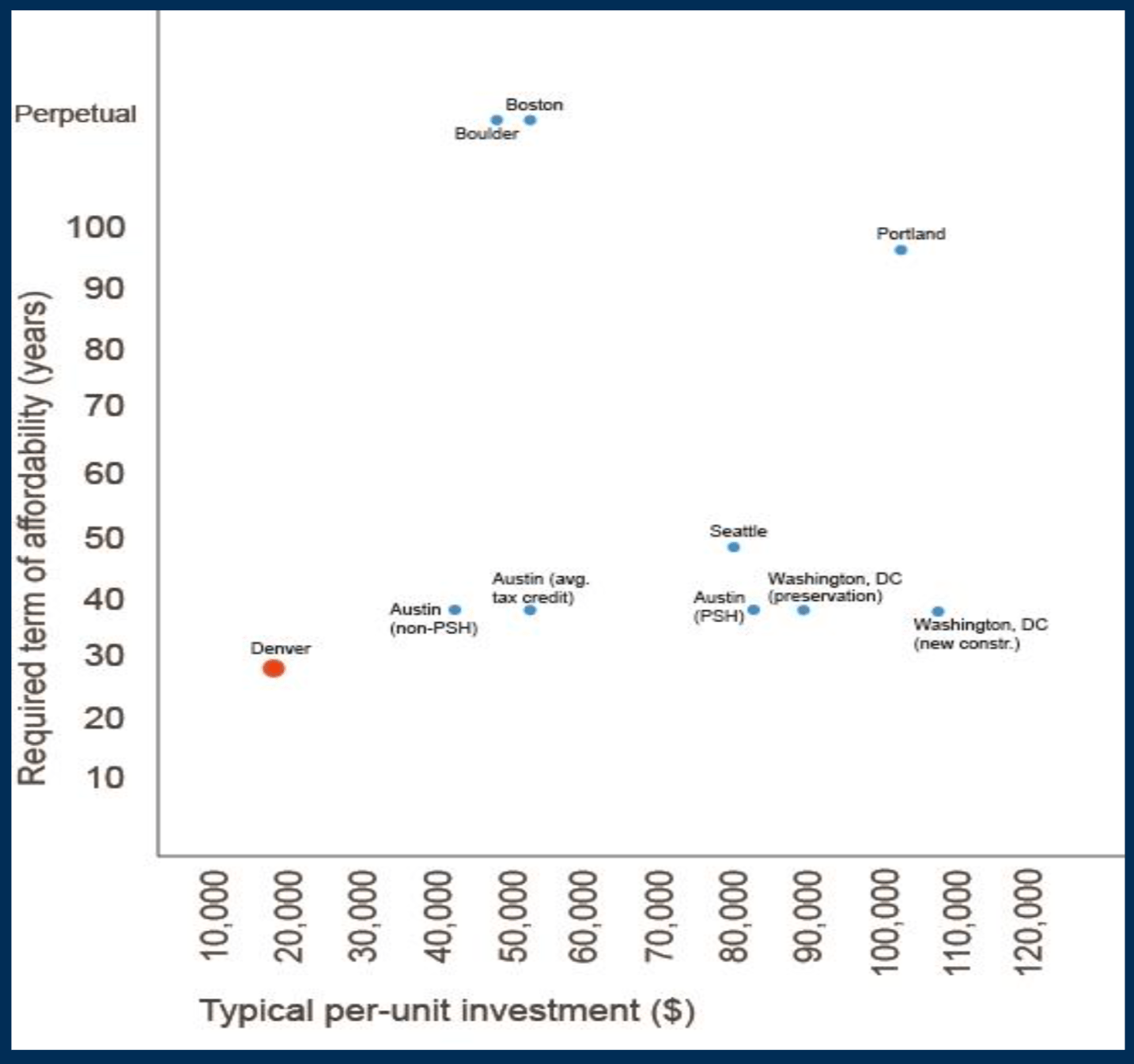

Denver's affordability window is slim compared to its peer cities. Boulder and Boston keep city-subsidized units affordable in perpetuity, according to a study by the Denver Office of Economic Development. Portland, Seattle, Austin, and Washington, D.C., all have larger affordability window, ranging from 40 years to 99.

But every of one of those cities invests more per unit than Denver.

"It's not apples and oranges," Barela said.

Councilman Rafael Espinoza favored an amendment that would pause the debate and restart it four months later. He scoffed at his colleagues' decision to "make a statement" at what he perceived to be a premature time. He called that line of thinking "Trumpian."

"You demean us as a body, and you demean this chamber," said Council President Jolon Clark, who cut Espinoza off with several pounds of the gavel.

Espinoza later said his comments were misinterpreted.

The final vote was 8 to 4 with Council members Paul Lopez, Wayne New, Debbie Ortega, and Espinoza voting for the delay. They all supported the 60-year minimum, however, which the full council will vote on Monday.